Conflict, Time, Photography

Tate Modern until 15 March 2015

Conflict, Time, Photography

Edited by Simon Baker and Shoair Mavlian | Tate Publishing | $49.99

The exhibition Conflict, Time, Photography, currently showing at Tate Modern in London, catches the wave of what has come to be known as “aftermath photography” – the visual record of what happens after the tumult has died. Aftermath photography, sometimes called “late photography” (a term that has an oddly dismissive, missed-the-boat tinge to it), is in effect the documentation of consequences, most often of cataclysmic events – war, displacement, natural disaster. Conflict, Time, Photography, as the exhibition title sort of suggests, focuses on the consequences of war, taking us, in the words of Chris Dercon, the director of the Tate Modern, “beyond the conventional association of war with photojournalism and the immediacy of reportage.” Dercon continues this theme, in his afterword to the exhibition catalogue, by contrasting the “immediacy” of photojournalism and, by implication, genres such as street photography, with the kind of image that “can sustain deep reflection on moments in the distant past, their repercussions in the present and even possible alternative projected futures.”

The photographic image, once created, belongs immediately to the past. But aftermath photography adds further layers to this quality of pastness, inviting the viewer to pause, and to acknowledge and reflect on events that once, a little or a long time before the photograph was taken, caused great suffering and are still, in a variety of ways, causing suffering today. Images of the precipitating event – the battle or the bombardment or the natural catastrophe – rarely appear in aftermath photography; attention is paid instead to the results, which may be obvious from the subject of the image – a ruined building, for example – or may be elusive and even impossible to discern without accompanying explanation. Even with the benefit of additional information, the import of many aftermath photographs may remain oblique, to be inferred or guessed at or imagined. Such photographs often work by inviting us to compare the apparent ordinariness or serenity of the subject with what we are reminded once took place on that spot – the effect of the image is thus significantly altered by what we are told, in the exhibition captions or catalogue notes, or in some cases in text that is included in the image itself.

Aftermath photography capitalises on another inherent quality of the photographic image – its stillness. In contrast to the destructive action that has occurred at some point in the past, the aftermath photograph typically captures the stillness and the silence of what came next, whether that “next” is, to adopt the organising terminology of the exhibition, moments or decades later. Conflict, Time, Photography includes several images that were made just moments after the main event, among which is Luc Delahaye’s US Bombing on Taliban Positions from 2001. The title suggests action, but in fact it is if anything a landscape picture, its stillness and bare beauty enhanced and even exaggerated by the size of the print. Made with a large-format camera, the print stretches almost two and a half metres across the wall, the landscape it depicts bisected on a semi-diagonal by a trench that runs the full length of the frame. It is an aesthetically satisfying image, formal, composed, restrained. In the upper centre of the frame is the “aftermath,” the plume of residual smoke that betrays the bombardment that has just taken place. The sky behind is streaked with cloud. To the right, and far back into the exaggerated depth of field, are several more wispy plumes rising from the plain.

Luc Delahaye, US Bombing on Taliban Positions, c. 2001. © Luc Delahaye

This photograph from 2001 marks a deliberate change of direction for Delahaye, a Magnum affiliate who had been dashing from trouble spot to trouble spot as a successful photojournalist and war reporter. In an exhibition of his more painterly, post-conflict images, held at the Getty Museum in 2007, he was described as being newly focused on the “long-term implications of current events that go well beyond their initial moments in the headlines.” It is not an uncommon story, the action photographer whose interest turns to outcomes. At the same time as the action photograph was progressively ceding ground to film and video – from which, after all, a screen grab can always be extracted as required – photographers like Delahaye were looking to reinvest the still image with its capacity to hold the viewer’s attention over time, and to encourage contemplation. In this respect, the increasing popularity of aftermath photography is a function of the changing technology over the past fifteen years, and of professional photographers’ desire to retain the power of the still image to keep us watching. The moving picture does this – keeps us watching, that is, at least for a little while – almost by default, as it dances around on the screen. The photograph has to work harder to capture and retain our interest.

Other factors have also been at play, as suggested by an image in the “Moments Later” category of Conflict, Time, Photography, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s The Press Conference, June 9, 2008, The Day Nobody Died (2008), part of a sequence with the overall title of The Day Nobody Died. Broomberg and Chanarin travelled to Afghanistan in 2008 as photographers embedded with the British armed forces, a process widely believed to have left the practices of conflict journalism and photojournalism irretrievably compromised. “Embedding,” according to the exhibition notes, “is a system invented by the army to control the way journalists report from the theatre of war, and has led to a far more sanitised reporting” (a charge that has assumed the truth of repetition, without necessarily having being proven). Yet in reading Broomberg and Chanarin’s commentary on their own work, it is not always clear whether it is the practice of embedding that is the problem in this case, or the super-saturated age we live in, by which images that might once have been expected to shock or discomfit are no longer capable of evoking sympathy, even when, or perhaps particularly when, that is the clear intention. For Broomberg and Chanarin, “images that are constructed to evoke compassion or concern, pathos or sympathy” have become “increasingly problematic.”

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, The Day That Nobody Died, 2008, installation view. Broomberg & Chanarin

Of all the photographs in the exhibition, The Press Conference, June 9, 2008 is the most removed visually from the events it is inviting us to acknowledge and to reflect on. Viewed in isolation, it offers the fewest clues to the nature of its subject. In fact it is not a photograph at all in any conventional sense, but the result of exposing, in the burning Afghan sun, a roll of light-sensitive photographic paper. “On the first day of our embed,” the photographers recalled not long afterwards,

a BBC fixer was dragged from his car and executed and nine Afghan soldiers were killed in a suicide attack. The following day, three British soldiers died, pushing the number of combat fatalities to 100. That was followed by a suicide attack on a group of Afghani [sic] soldiers killing all eight. On receiving the news of his brother’s death in that ambush, another Afghan National soldier turned his M16 to his chest and pulled the trigger. The title of the project refers to the fifth day of our embed, the only day in which nobody was reported to have been killed.

In responding to these and other events, Broomberg and Chanarin “removed a six-metre section of light sensitive paper from our box, in the back of an armored vehicle which we had converted into a mobile darkroom, and exposed it to the sun for twenty seconds,” resulting in an image that almost, if not quite, creates itself, by relying not on the photographer’s eye but on “the temperature of light on that day, at that moment, in that place.” The image that was made by this method, on the day that nobody died, consists of bands and blobs of blue and white and orange stretched out across the gallery wall; it represents not so much a response to an event as a response to its absence. By Broomberg and Chanarin’s own account, the image constitutes an act of resistance against their official status as embedded photographers. It is an “invitation to contemplate,” an injunction “to look harder.”

During the period of their embed, Broomberg and Chanarin produced a half-hour video, also called The Day Nobody Died. It follows the journey of the box of photographic paper from London to Afghanistan, as it is first of all loaded on to the baggage travelator in London, then retrieved from the carousel at Baghdad airport, then lifted and transported by serving soldiers from one conflict zone to another. The journey of the box is described, in tune with the times, as a “performance,” and as a component in a kind of “Dadaesque stunt.” At the same time, it is clear from their commentary on the entire Afghan experience that Broomberg and Chanarin were not simply detached observers, playing games with the system, but were moved and unsettled by the events they witnessed, and stuck for an adequate response.

Their answer is, essentially, a political one. Faced with the much-remarked fact that there are an awful lot of photographs around these days, competing for our attention, Broomberg and Chanarin stress the need “to realise that even though so many are made, they are still so carefully controlled, by newspapers, by news agencies, by the state. We see very little of what’s really going on unless we look hard.” The Press Conference, June 9, 2008: The Day Nobody Died, to give it its full, deceptively precise title, encourages us to see what is really going on, ironically enough by showing us an image that could, without the context that the photographers provide, be about almost anything. It is the context, including the display of the image in an exhibition called Conflict, Time, Photography, that sets us thinking. Looking hard at the bright colours of the image, it is not entirely fanciful to see a blue sky overlaid by a white cloud, an analogue of the clouds and the plumes of smoke in Delahaye’s US Bombing on Taliban Positions.

Toshio Fukada, The Mushroom Cloud – Less than Twenty Minutes After the Explosion, 1945. Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo

Clouds and smoke recur frequently in aftermath photography, as embodiments of the traces left by the cataclysmic event, traces that have already changed and re-formed and that will continue to change and re-form over time. The Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, in memorialising the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, sixty-five years later, photographs the sky every morning from the balcony of his apartment. In an image taken from Araki’s series “Tokyo Radiation August 6–15, 2010” (2010), date-stamped in the bottom right-hand corner, we are encouraged to read, in an otherwise unremarkable image of a cloudy sky, allusions both to the cloud of memory and to the immediate aftermath of the bombing itself, when a huge cloud, described by survivors as pink and orange, dominated the sky. This “late photograph” by Araki alludes to predecessor images by Toshio Fukada, made shortly after the bomb was detonated over Hiroshima. The Mushroom Cloud – Less than Twenty Minutes After the Explosion (1945), seems to pack all the consequences of the destructive force of that day into the thick, dense cloud that fills the frame.

The images on display in Conflict, Time, Photography span almost the entire history of the medium, underlining a contradiction in the exhibition as a whole that is never quite addressed. Aftermath photography is presented both as something new – a genre about consequences that is itself a consequence of recent changes in technology and the changing way we interact with images – and as something old, with roots in the early days of photography. As is the case with almost all photographic genres, examples of aftermath photography appeared very early on. Several of the images in Conflict, Time, Photography date from the mid nineteenth century, when photography was a laborious business, involving heavy equipment and delicate, time-consuming processes of image capture and development, with the prospect of rapid action shots still very much in the future. These limitations meant that photography was largely confined to recording stillness rather than action, the aftermath – or the prelude – rather than the event.

Aftermath images of the Crimean war, made by the photography pioneer Roger Fenton, continue to exert their influence on practitioners of the genre today. Fenton’s images of Valley of the Shadow of Death (1854–55), taken “two months later,” show a desolate, unpeopled road that had been relentlessly bombarded by Russian cannon. In one of the photographs (below), cannon balls are scattered across the road and alongside it. In a companion image, the cannon balls are largely absent, with only a relative few lying in the shallow ditch beside the road. Which of the images reflects the scene as it was? Had either setting, or both, been “dressed” beforehand? Were some cannon balls deliberately added between times, or some taken away? Such questions, when applied to photojournalism or street photography, genres that are predicated on the overriding importance of catching the true and “decisive” moment, continue to be urgently debated. Yet when applied to aftermath photographs the questions seem less urgent, even irrelevant. Indeed the exhibition contains many images that have been manipulated, amended or elided in some way in order to engage the viewer and elicit a response.

Roger Fenton, Valley of the Shadow of Death, 1854–55. Victoria and Albert Museum

Meanwhile Fenton’s road, extending as it does through the valley and on into the middle distance, continues today as a powerful trope of aftermath photography and the complex and never quite finalised outcomes of war and conflict. In Don McCullin’s The Battlefields of the Somme, France (2000) or Ursula Schulz-Dornburg’s images from her series Train Stations of the Hejaz Railway (2003), we can see newer versions of Fenton’s early work, where the events that took place on this spot must be reimagined, and some sense made of what has happened since. Similarly themed photographs, not included in the exhibition, such as Paul Seawright’s Valley, taken in Afghanistan in 2002, can be read as direct homages to Fenton. Seawright’s image is both a prelude and an aftermath, alluding to violence that has happened and, in its depiction of ordnance on the ground, violence still to come. In all these photographs the sky, whether cloudy or clear, takes up the top third of the frame, suggesting our capacity to acknowledge and remember past catastrophes while looking beyond them, past the clouds and the smoke. But when the sky is excluded or squeezed out or almost entirely darkened over – as it is in the images derived from Sophie Ristelhueber’s series Fait (1992), a project she undertook seven months after the end of the first Gulf war – the effect is more claustrophobic, less reassuring, as if we are deluding ourselves if we think that we have learnt anything or that the future offers better prospects.

Looking at aftermath photographs, one thing is clear: with a few exceptions, they do not work by themselves. When they do, it is partly because of their iconic status – we already know the story without having to read the notes – and partly because the image is so strong in itself that the “story” is contained within it, without the need for explication. Don McCullin’s Shell-shocked US Marine, Vietnam, Hué (1968), included in the “Moments Later” section, meets both these criteria. It conveys its powerful impact without the need for explanation or context, without even the need for the caption. Shomei Tomatsu’s 1960s photographs of the aftermath of Nagasaki, particularly those showing the keloid scars on the faces and bodies of survivors, have a similar, stand-alone impact. And the same might be said of Pierre Antony-Thouret’s Reims After the War (1927), with the ruins of Reims Cathedral on stark display, the contrast between the building’s still obvious grandeur and its subsequent destruction making its own powerful point. But for the most part some context and explanation are required, if the viewer is to successfully make the link between the unseen, singular event – the conflict of the exhibition’s title – and the depiction of its aftermath.

Don McCullin, Shell Shocked US Marine, Vietnam, Hue, 1968. © Don McCullin

In this respect, many of the photographs, and the series of which they are often a part, smack too much of an idea, a thought-up project that meets the definition of aftermath photography but fails somehow to involve the viewer, as we feel we should be involved, in the process of memorialisation and remembrance and regret. Extracts from two projects by Taryn Simon illustrate the risks of this approach. In one of them, A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters (2011), Simon documents the “impact on one bloodline” of the Srebrenica massacre of 1995. Some of the many components of what is in effect an installation are listed in the exhibition notes: “the large panel on the left orders members of one family directly related by blood.” Interspersed among small-format portraits are “images of bone samples and the reassembled remains of those who were killed,” followed by text and footnote panels, and film stills. Simon travelled the world for four years, pursing the aftermath of the massacre, researching bloodlines and the stories that arose from them. Her website lists some of the disparate subjects that came out of this period of intense and comprehensive research: “test rabbits infected with a lethal disease in Australia, the first woman to hijack an aircraft, and the living dead in India.” In contemplating these disparate yet connected narratives, we are invited to also contemplate “the space between text and image, absence and presence, order and disorder,” which in the end seems almost too general and sweeping, too remote from the specific and terrible event.

Where aftermath photography is concerned, the space between intention and result is a particularly difficult one to bridge. Sometimes an aftermath photographer will articulate his or her personal passion for the project, as though something of that articulated passion might transfer itself to the images and heighten their impact. In the notes to Sophie Ristelhueber’s photographs of the aftermath of the first Gulf war, when the desert had been turned into a “scarred and damaged landscape,” we learn that Ristelhueber had “become obsessed” with her subject. Similarly, we are told in the catalogue how Paul Virilio “became fascinated by the monumental concrete bunkers” that remained as evidence of German coastal defences from the second world war. Photographs that Virilio made between 1958 and 1965 of these massive, proto-brutalist structures went on to form the sequence Bunker Archaeology, published in 1975 to accompany an exhibition at the Pompidou Centre. Not everyone is equally fascinated. For Alex Danchev, reviewing the exhibition in the Times Literary Supplement earlier this year, “‘bunker archaeology’ is boring,” suggesting how difficult it can be to transmit fascination, or obsession, from photographer to viewer.

On the other hand, the archaeology of the photographs themselves can hold its own interest. Virilio’s bunkers are monumental and a bit scary, even if the scariness is rather like something out of early Doctor Who. The distance in time between the end of the war and the taking of the photographs, some fifteen to twenty years, is not very great, not even half a generation, not long enough for these evocative structures to lose entirely their air of threat and danger. But in a much more recent photographic rendering of the same subject, arising out of what can be assumed to be an equal fascination with coastal defences, Marc Wilson’s photographs from a 2014 exhibition show these second world war bunkers and other oddly shaped, assertive concrete structures in a more benign, even nostalgic light, as they seem to be relaxing their vigilance and folding slowly back into the landscape.

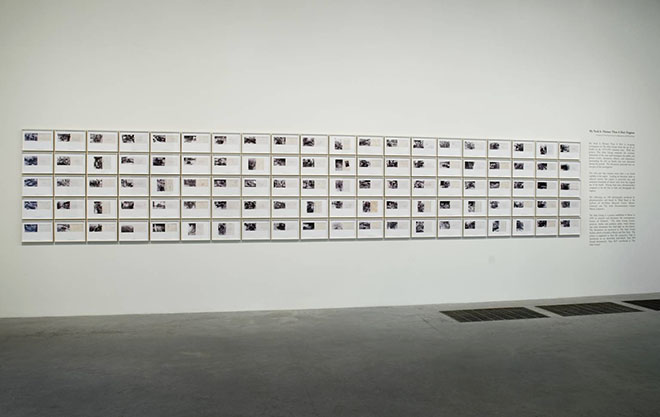

Many of the photographs in Conflict, Time, Photography are drawn from longer sequences, which might have first appeared in books, for example, where the impact of the images is typically both cumulative and complementary. Isolated from their fellows on a gallery wall, they do not always work as well as they might. Others lose nothing, and perhaps even gain, from being singled out. Two photographs by Chloe Dewe Mathews, for example, are part of a larger sequence entitled “Shot at Dawn” (2013) in which Mathews records the sites where Allied soldiers were executed for desertion and cowardice during the first world war. Even without their companions, these two large-format images strike a note of high drama that fills the gallery space. On the other hand, Walid Raad’s My Neck Is Thinner than a Hair: Engines (2000–03), a composite image of one hundred photographs complete with notations, which harks back to the Lebanese civil war of 1975–91, gets a bit lost, despite its size. The individual photographs that make it up, hung together on the wall, are too small and too far away.

Atlas Group, Walid Raad My Neck is Thinner than a Hair: Engines, 2000–03. © Atlas Group and Walid Raad, courtesy of Anthony Reynolds Gallery

When we look at My Neck Is Thinner than a Hair in the gallery, we are looking at an idea rather than a complete and realised work. But look at it online and the impact is quite different. The installation as a whole still seems a long way away, but when it is displayed digitally we can zero in on each of the hundred components and expand it to fill the screen. Raad has culled from the files of contemporary newspapers images of tangled metal and destroyed engines, the mechanical detritus of the epidemic of car bombs that plagued Beirut during the civil war. By the side of each photograph, the name of the photographer, if known, is recorded, and the date of first publication. In many of these photographs we see groups of men gathered round, half looking at the wrecked engine, half posing for the camera; the engines seem to act as surrogates for these men, foreshadowing their possible fate.

The individual photos, recovered from daily newspapers, were first collected and deposited with the Atlas Group, an online archive founded by Raad and others for the purpose of storing documents connected with the history of modern Lebanon. Included among the group’s digital files are some photographs taken by Raad when he was a teenager. Following the invasion of west Beirut by Israel in the summer of 1982, he set out with his mother to photograph the aftermath of the initial action. “I was fifteen in 1982,” he recalls, “and wanted to get as close as possible to the events, or as close as my newly acquired camera and lens permitted me.” In aftermath photography there is the crucial gap between the event and the making of the photograph. But there can also be a gap between making the photograph and making sense of it. “This past year,” Raad wrote in 2002, “I came upon the negatives from that time, all scratched up and deteriorating. I decided to look again.” In one striking image, its surface faded and damaged, we see a row of bombed-out buildings, with a plume of smoke rising from behind and up into the sky.

Raad’s anecdote suggests how the word “aftermath” can be applied not only to the period between the event itself and the time the photograph was taken, but also to the photograph’s continuing life, and our continuing propensity to respond differently and with greater understanding, according to how much time has passed. Against the increasingly common cultural perception that photographs are disposable – they are of the moment and the moment moves on – aftermath photography makes the case for the capacity of certain images to re-engage us over time. In that sense, the decision to arrange the photos in Conflict, Time, Photography according to how soon after the event they were made also has the effect of inviting us to reflect on what it means to “look again.” •