In years gone by, the federal budget would have given us a clear idea of the size of Australia’s immigration program for the year ahead. Now the figure is hidden somewhere in Peter Dutton’s head.

The migration planning level announced in last year’s budget was rendered largely meaningless when it was transformed from a “target” to a “ceiling.” The figure in this year’s budget will be similarly uninformative. For the first time since the second world war, Australians have no idea of the government’s real immigration target. It is entirely the preserve of the home affairs minister.

Judging from the minister’s past actions and what we know of his views, let’s try to work out what will happen to migration and humanitarian programs over the next couple of years — and, more importantly, what that means for net overseas migration, the number of long-term and permanent arrivals minus departures. We can then get some idea of the effect migration will have on the size and profile of our population.

One of the things we know for sure is that Peter Dutton cut the migration program by 6400 places in 2016–17. That was the gap between the ceiling of 190,000 places, which used to be a firm target, and the number of permanent visas issued by the home affairs department. Recent reports in the Australian suggest the minister is likely to cut the 2017–18 migration program by 20,000, which means around 170,000 visas compared with the ceiling of 190,000. The reduced program is still likely to maintain a two-to-one split between skilled and family migration, which means a likely skill stream in 2017–18 of 113,000 places and (after allowing for the small special-eligibility category) a family stream of around 56,000 places.

But there is another factor to take into account, and that is the impact of a new visa for New Zealand citizens who have been in Australia for many years and have an income of more than $53,900. In this financial year and beyond, these people have a right to apply for formal permanent residence and will be counted as part of the skill stream. Based on current application rates, some 10,000 places will need to be found in the likely 2017–18 program of 170,000. As the stock of long-term New Zealanders in Australia continues to grow, the government will need to continue to find more places for New Zealand citizens who have been in Australia long-term, which will effectively cut the intake.

These places will most likely be taken from the “skilled independent” visa category, which uses a points test and doesn’t require employer sponsorship. This category is also likely to bear the brunt of the overall cuts to the skill stream in 2017–18. In 2016–17, 42,422 skilled independent visas were issued, already some 1600 fewer than in the previous year. The number is set to fall much further: in December 2017 and January and February of this year, places in the category were released at around 30 per cent of the rate for the same period in the previous year.

Employer-sponsored visa numbers are also likely to fall, with fewer people applying following the tightening of requirements announced in April last year. Because these changes only took full effect from March this year, there is still a backlog of around 50,000 applications, which will take all of 2017–18 and much of 2018–19 to clear. Some 48,250 employer-sponsored visas were issued in 2016–17, making up around 39 per cent of the skill stream.

From 2019–20 the lower number of applications will force Peter Dutton to make the bulk of his cuts to the skill stream in employer-sponsored visas. Subject to the strength of the economy, employer-sponsored visa numbers in 2019–20 could fall back to around 10,000 per annum, the level prior to the major reforms introduced by the Howard government in the early 2000s.

The spectacle of a Coalition government reducing employer-sponsored visas will be another postwar first. These visas have traditionally had the highest policy priority because, according to the government’s own research, these migrants already have a skilled job, earn the highest average incomes, and thus make the largest economic and budgetary contributions. They generally have strong English-language skills and the occupational skills employers need, and they quickly integrate into Australian society. Targeting these visas for the largest cuts from 2019–20 seems strange, especially if the labour market continues to tighten.

Offsetting the declining application rate in employer-sponsored visas is the rapidly increasing demand for visas in the business innovation and investment program (around 7260 visas in 2016–17). By the end of June 2017, more than 15,000 applications for these visas were waiting on a decision. The minister will need to deal with increasingly urgent questions about the effectiveness of this scheme, and a tightening of the rules seems inevitable.

Based on his public statements about the importance of achieving a better dispersal of the immigration intake, the minister is likely to avoid cutting state-specific and regional migration visas, which together provided some 36,494 places in 2016–17 (around 30 per cent of the skill stream). But once these migrants have gained residency and fulfilled any medium-term obligations, nothing compels them to remain in the smaller states and in regional Australia. Questions remain about how many of these migrants do stay and whether this program succeeds in moving migrants out of the hotspots of Sydney and Melbourne.

The great bulk of visas in the family visa stream, meanwhile, go to the partners of Australian citizens and permanent residents. The family stream delivered 56,220 places plus 3400 child visas in 2016–17, a total of 59,620 visas, or around 32.5 per cent of the total program. As we’ve seen, the minister will need to reduce the overall family stream to around 56,000 visas.

He is likely to maintain the number of partner visas at around 47,800, as the government has over the past four years, and the child category at around 3400. As the Migration Act doesn’t allow the minister to cap the number of spouse and dependent-child visas, departmental officials will increasingly use administrative measures to limit the number granted, but this approach must eventually run into legal obstacles (as well as complaints from Australian citizens who are unable to reunite with their foreign partner or child).

Cuts in the family stream will therefore focus almost entirely on parent visas, 7563 of which were issued in 2016–17. The parent category and the small “other family” category will need to be reduced by up to 5000 places. As demand for partner places is likely to continue to rise, partner and child visas may in future years become close to 100 per cent of the family stream.

That leaves the humanitarian program, through which 21,968 visas were issued in 2016–17 — a figure that included some of the additional 12,000 places for Syrian refugees. The 2017–18 program offers 16,250 places, and prime minister Malcolm Turnbull announced in 2016 that Australia’s humanitarian program in 2018–19 will be 18,750.

At this stage we don’t know whether any South African farmers will be included in the humanitarian program. If Dutton fails to attract enough South African farmers, will he be tempted to treat the humanitarian program target as a ceiling too?

What impact will these changes have on net overseas migration? This is a key question, because net migration is a much better indicator of the impact of migration on Australia’s population growth than the size of the permanent program. Net migration surged from 193,000 in 2015–16 to 245,400 in 2016–17, one of the biggest single-year increases in our postwar history. But it is set to decrease in 2018–19, despite the recent strengthening of the economy, partly because of these changes in the migration program.

Other factors will also contribute to a decrease in net migration. At the most basic level, changes in the economy and the job market could produce significant fluctuations in the contribution of Australian and New Zealand citizens to the net migration figure in 2017–18 and 2018–19.

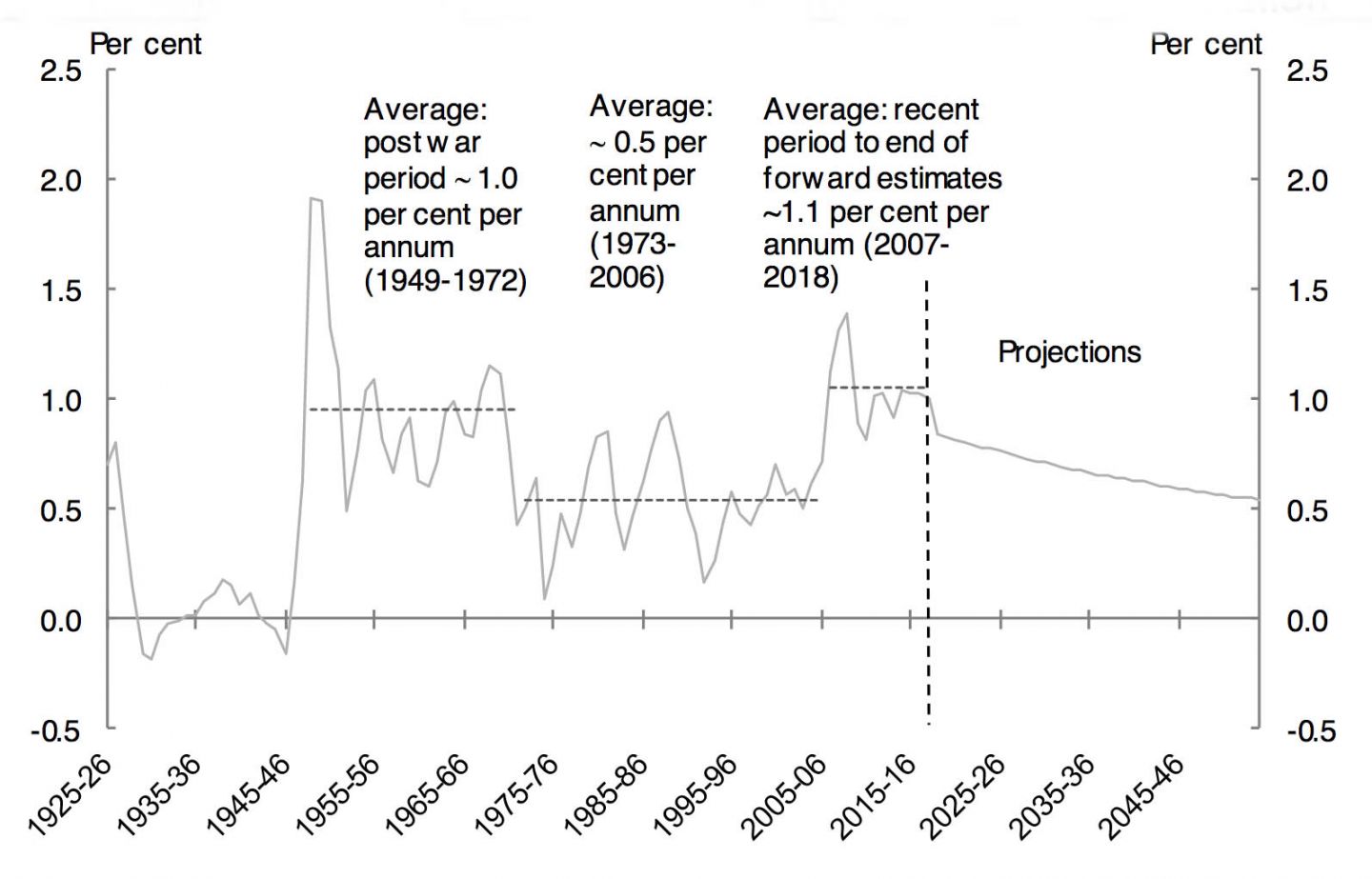

Net overseas migration as a percentage of the Australian population since 1925–26

On top of that, the tightening of skilled temporary entry options (including the high-profile abolition of sub-class 457) will reduce options for overseas students, working holiday-makers and visitors, who have previously been able to change status more readily to skilled temporary entry or employer-sponsored permanent migration. Temporary entry visas have been crucial to Australia’s immigration framework, providing a pathway to extended stay and/or permanent residence.

And finally, overseas students will play an important role, their numbers affected by a range of factors in addition to the tightening of the skilled temporary entry options. Here, there are three big questions. First, will a much larger number of overseas students in Australia depart once they have completed their courses, either because they see better opportunities elsewhere or because they can’t find a pathway to permanent residence in Australia? Overseas student departures have been relatively stable at around 45,000 per annum; arrivals have increased rapidly. The number of departures can be expected to rise significantly in the next few years.

Second, how will the rapidly growing stock of temporary graduate visa holders (currently over 50,000 and rising at over 15,000 per year) respond to the significant narrowing of opportunities to obtain permanent residence? These people have spent on average five to seven years in Australia, studying and/or working, and paying taxes, but have had little or no access to government services and benefits. Having made a substantial investment in Australia, many will be caught in limbo — unable to stay and unable to afford a return home. How the government manages this very large group will have long-term implications for Australia’s international education industry and its ability to attract a growing share of the world’s overseas student market.

Third, how will potential new overseas students respond to the tightening of the permanent residence pathway? When the Rudd–Gillard governments tightened these pathways in 2009, overseas student numbers dropped very sharply. While the response this time may not be as dramatic, some tempering of growth in overseas student arrivals can be expected.

From 2018–19, with a rising number of temporary entrants unable to extend their stay, we are likely to see a rise in long-term departures. Simultaneously, long-term and permanent arrivals will fall as the migration program is scaled back. Net migration in 2018–19 is likely to be less than 200,000, and possibly significantly so. Assuming no significant change in relative economic conditions or further change in immigration policy settings, net migration may continue to decline into 2019–20.

Net migration at well below 200,000 per annum means Australia’s population growth rate will fall at a faster rate than projected by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, which has been working with a middle assumption for net migration of 240,000 per annum. As the reductions will focus on generally younger entrants — mainly overseas students, working holiday-makers and skilled temporary entrants — who could previously take advantage of more open pathways to permanency, the rate at which Australia’s population ages will accelerate faster than the ABS projects.

The government’s intergenerational reports have repeatedly shown that a more rapid rate of population ageing will reduce per-capita economic growth. A slower rate of growth in the working age population will reduce the job growth figure the government is fond of highlighting. No wonder Scott Morrison is pushing back against Tony Abbott and Peter Dutton’s desire to reduce immigration. As the treasurer has already noted, a reduction in skilled migration will have a negative impact on the budget. But it seems he does not have the leverage to seek offsetting savings from Dutton’s portfolio as he would from any other minister who proposes measures that have a negative impact on the budget. ●