The Batman by-election puts the Greens back into the political spotlight. With so many parties in our parliaments now, they had largely slipped from sight. But if conventional wisdom is right, they are about to change the momentum of Australian politics by taking a seat from Labor.

Whether the conventional wisdom is right is debatable. For now, though, the bookies have the Greens as heavy odds-on on favourites to win on 17 March — and the cognoscenti agree. If they’re right, that will deflate Labor’s tyres as it enters the turn into what is expected to be an election later this year. And that matters.

Inevitably, the by-election will be portrayed as being about Labor, and about Bill Shorten’s leadership in particular — especially by the Murdoch press and others in the media for whom Labor is the ideological enemy. You’ll have to put up with all of that — but remember, under the rules introduced in 2013 by Kevin Rudd, it is virtually impossible to mount a Labor leadership challenge before an election. Shorten will almost certainly lead Labor into the next election.

But the by-election is also partly about the Greens. It must be, because Batman tops the list of the seats they have targeted. At the 2016 election, they actually came closer to winning Melbourne Ports, but Batman was their priority, and they missed it by only 1.03 per cent. In net terms, fewer than one in fifty Labor voters need to shift to the Greens on 17 March to give them the seat.

The Greens are often assumed to be a receding wave: and it’s true that their vote in federal elections peaked at 11.8 per cent in 2010. But this is at odds with another reality: the Greens continue to expand their core territory and parliamentary numbers. Last year they won the Northcote by-election in Victoria, their first seat in the Queensland parliament (Maiwar) and four seats in Western Australia’s upper house. They now sit in every parliament but for the Northern Territory’s.

Look at it another way. If we take the major parties as Labor, Liberals and Nationals, then on my count, Australia now has fourteen minor parties sitting in its federal, state and territory parliaments. Between them, they hold seventy-three seats. Of those, the Greens have thirty-eight, leaving the other thirteen parties with just thirty-five between them. (One Nation is next with seven.)

Back in 2010–11, the Greens’ parliamentary numbers peaked at thirty-five. Since then, their vote in most of Australia has fallen, but their parliamentary representation has rebounded to the highest level of any third party in our history. How do we explain this?

On one hand, we now have more — and more serious — competition all over Australia for a share of the “don’t want either of them” vote. The number of minor party and independent candidates for the House fell in 2016, but remained very high. Six or seven candidates contested the average seat in the House, and a shade over eight candidates competed for every seat in the Senate.

Most importantly, we now have more minor parties with enough support to be contenders for seats in parliament — that’s why we have fourteen of them sitting in our parliaments. Since 2010:

● Pauline Hanson and One Nation have been reborn as a significant political force.

● Nick Xenophon and Bob Katter, formerly independents, have formed their own parties.

● Cory Bernardi has left the Liberals to found the Australian Conservatives, absorbing Family First and the remnants of the DLP.

● Animal Justice has splintered off part of the Greens’ core constituency, and won a seat in the NSW Upper House.

I have argued before that the main reasons why the vote of the major parties has plunged are the growth in the number of parties we can choose from, and the increasing diversity of the society they represent. The same factors explain part of the decline in the Greens vote since 2010.

In South Australia, Nick Xenophon’s new party now hogs all the sunlight; it now owns the ground the Greens had hoped to occupy, including Mayo, which had been the Greens’ best prospect in the Lower House. By removing Sarah Hanson-Young as the party’s voice on the refugee crisis — a seriously bad mistake by party leader Richard di NataIe — the Greens have not only smudged their position on the one issue that most differentiates them from Labor, but removed her from the spotlight, making it unlikely that she will retain the only federal seat the Greens now have in the state.

In Tasmania, the Greens have been widely blamed for the failure of the last Labor–Greens coalition. While their vote is slowly rebounding from the thrashings in 2013–14, many voters have yet to forgive them. Andrew Wilkie has cemented his hold on the seat they most coveted, Denison, making Hobart the only place in Australia where their vote was lower in 2016 than in 2004.

The NSW branch was widely seen as controlled by the left faction of senator Lee Rhiannon, and has suffered electorally. In voting support, it has sunk from being one of the Greens’ stronger states in their early years — when they briefly took the Federal seat of Cunningham from Labor at a by-election — to being one of its weaker ones. Only the federal seat of Richmond, home of the north coast’s alternative culture, is even within their range.

Rhiannon’s recent preselection loss to moderate MLC Mehreen Faruqi might signal that that era is ending. At state level, the Greens have not lost ground in terms of seats. The last NSW election saw them win three lower house seats — Ballina from the Nationals, and Labor’s former inner city strongholds of Balmain and Newtown. It is possible that in Sydney, at least, the Greens might rebound.

But in other states, the Greens have held their ground better. Western Australia is marking time. Their vote in the west is still below the peak levels of 2008–10 (when they won the state seat of Fremantle from Labor at another by-election), and they have no state or federal lower house seats within reach. But they unexpectedly outpolled One Nation at last year’s state election, and won four of the thirty-six upper house seats, to share the balance of power.

In Queensland, the Greens are clearly on the rebound. In 2016 they won their first seat on Brisbane council, the nation’s most powerful municipality. And in November’s Queensland state election, when the focus was on One Nation, the Greens captured a record 10 per cent of the vote. They won their first state seat, Maiwar, in Brisbane’s inner west, and came close in McConnell and South Brisbane. Unfortunately for them, all three are separate federal electorates (Ryan, Brisbane and Griffith).

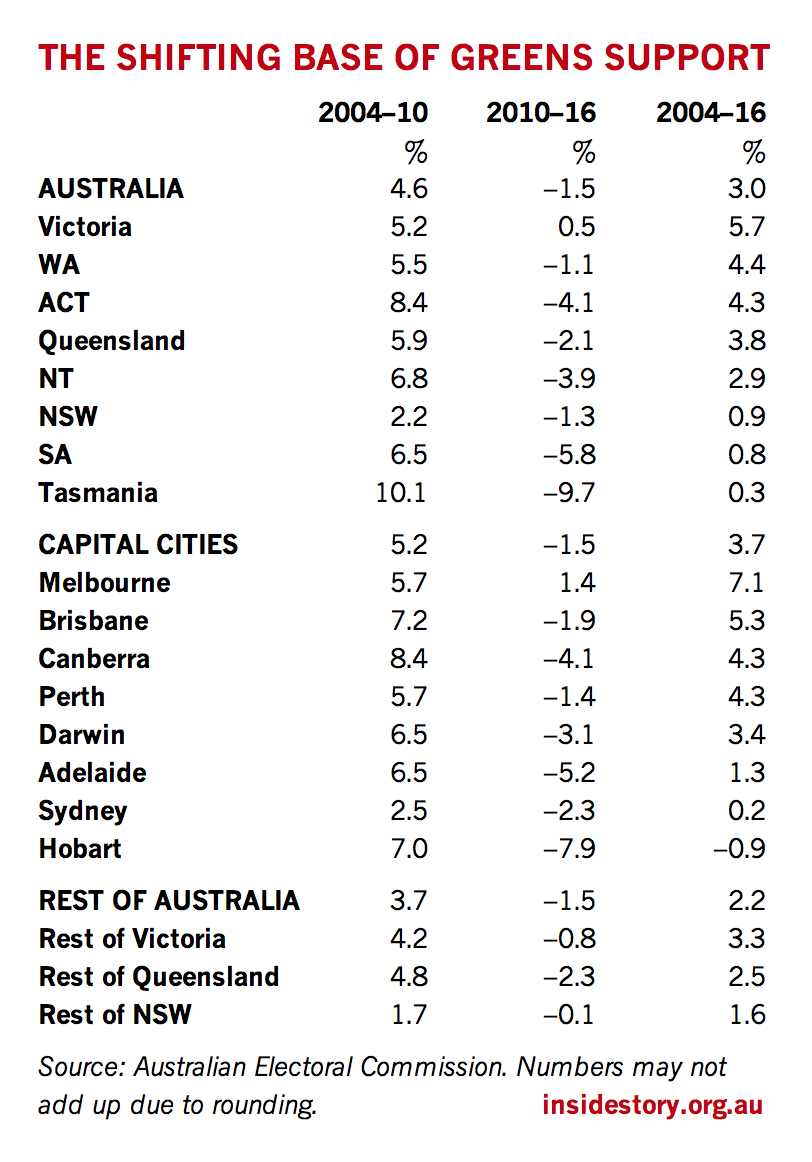

Then there is Victoria. As the tables show, the really startling development in this decade has been the speed of the Greens’ expansion through inner Melbourne.

At the 2016 federal election, the Greens polled 15.5 per cent of the vote right across Melbourne, compared with 9 per cent in Sydney, 11.3 per cent in Brisbane, 12.3 per cent in Perth, and just 7.1 per cent in Adelaide (the Xenophon effect). They retained the seat of Melbourne easily, came very close to winning Melbourne Ports (0.6 per cent) and Batman (1.0 per cent), got within dreaming distance in Wills (4.9 per cent), and even went half-way to their implausible goal of taking the Liberal seat of Higgins (8 per cent).

It’s an astonishing contrast. In the rest of Australia, the only seat where they even got within dreaming distance was way up north in Richmond (where a 4.9 per cent swing from Labor would give them the seat). Yet in Melbourne, they might well have won a second seat had they focused on Melbourne Ports instead of Higgins. They now have a roughly even chance of taking Batman — and depending on how the Victorian redistribution goes, they could go into the next election with a real chance of winning four inner-Melbourne seats.

The Greens began as a Tasmanian party, then linked up with sister parties in Sydney and Perth and went national. Yet now their core territory has become inner Melbourne, and their chances of expansion are concentrated there.

By contrast, they have made no progress in inner Sydney — and they’re unlikely to while Tanya Plibersek remains in Sydney and Anthony Albanese in Grayndler. Greens leader Richard di Natale has talked of targeting twenty-five seats the Greens could win in the long haul, but that is pie in the sky.

The battleground is inner Melbourne. And, except for the state seat of Prahran, all the seats the Greens have won or have serious chances in are Labor seats. The party’s core support comes from young voters and disillusioned Labor voters, primarily educated ones. That makes it difficult for Labor and the Greens to reach the political understandings they urgently need to make — at federal and state level — to put at rest the Liberals’ battle cries about the dangers of minority governments.

Much as the Greens try to present themselves as targeting both sides equally, there is little evidence that their rise has cost the Liberals much in votes or representation (as the table here shows). In Sydney and Melbourne, they’ve replaced Labor as runners-up in some safe Liberal seats — Higgins in Melbourne and Warringah in Sydney in 2016, as well as a swag of North Shore seats at the 2015 NSW election. But they didn’t come close in any of them. Higgins has too much Liberal heartland (Toorak, Armadale, Malvern) to ever be a Greens seat, and in Tony Abbott’s Warringah they won just one polling booth out of dozens, and by only thirteen votes.

Inner Melbourne is where the contest is. And Batman is its central battleground. If the Greens are ever to win the seat, this should be the time. It’s a by-election, which tends to favour challengers. If the Liberals don’t stand, as the PM has indicated, their preferences won’t rescue Labor. The Greens’ win in the Northcote by-election has created a widespread consensus that Batman will follow. In most commentaries, it seems almost as if gravity will ensure that victory.

Pardon me if I disagree. The bookies’ odds imply a 70 to 75 per cent chance of a Greens victory, and only a 25 to 30 per cent chance of Labor holding the seat. I think it’s more like 50–50.

Why? First, as Inside Story alone seems to have reported, the result in Northcote showed a swing of 5.3 per cent to Labor — and against the Greens — from the result at the 2016 federal election. There are all sorts of reasons why that might have happened: federal and state elections are different, and for years some voters in Northcote have leaned to the Greens at federal elections and to Labor at state elections. But why — and will that happen again on March 17?

There’s no doubt that the Andrews government in Victoria is to the left of federal Labor: its recent passage of politically hazardous legislation allowing terminally ill patients the right to die was a classic and courageous example. Federal Labor’s bipartisan support for a policy of leaving refugees to rot in offshore camps is a converse example of what makes it hard for many-inner suburban voters to vote its way in federal elections.

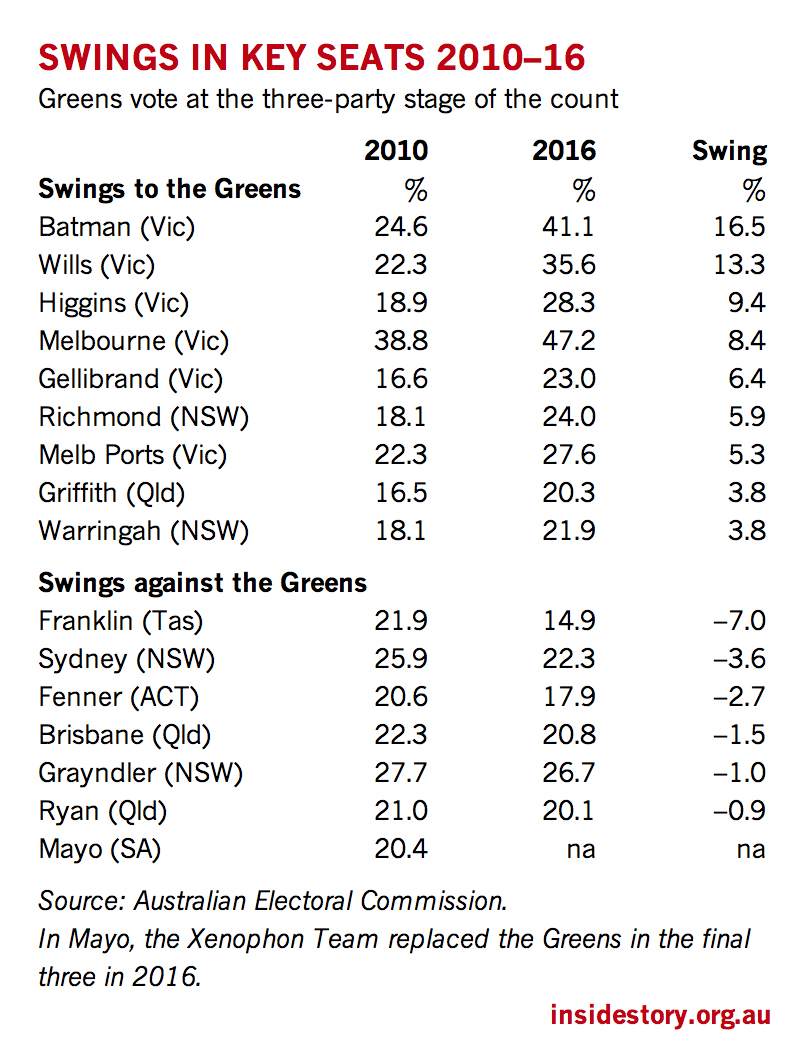

But there’s clearly a second reason, specific to Batman. Look again at that panel on the swings in key seats. Since 2010, there has been a bigger shift to the Greens in Batman than almost anywhere else in inner Melbourne, let alone in the rest of Australia. At the crucial three-party stage of the count — which determines who makes the final count — the Greens vote has soared from 16 per cent in 2004 to 24.6 per cent in 2010 and 41.1 per cent in 2016. That is such an outlier that it must have some explanation specific to Batman.

The conventional wisdom, which I believed until recently, is that MPs in the cities have only a small personal vote. In the country, it’s different; but in the city, most voters don’t know who their MP is, let alone support them because they like them. But the size of the swing against Labor in Batman since David Feeney won preselection has made me go deeper into the data — and in fact it suggests that some urban MPs certainly do influence their own vote, positively or negatively.

Senate votes are counted by electorate; in some cases, they are very different from the way the same people voted a minute earlier for the House. As a rule, of course, a party’s House vote is much higher than its Senate vote, because it faces fewer opponents. In Gippsland, for example, the Nationals’ Darren Chester polled 56.3 per cent of primary votes, but the same voters gave his Senate colleagues only 37.9 per cent — with many of them voting instead for Ricky Muir, One Nation, the Shooters Party and even Labor.

By contrast, Feeney’s vote in Batman was only 0.4 per cent higher than Labor’s vote in the Senate. Next door in Jagajaga, his colleague Jenny Macklin polled 9.6 per cent higher than the Senate vote. Her vote went up by a third from the Senate vote; Feeney’s remained flat. Among Labor MPs in Melbourne, they were the bookends: Macklin attracted the biggest personal vote, Feeney the lowest.

Instead, the personal vote in Batman went to the Greens’ Alex Bhathal. A second-generation Indian migrant, social worker and Sikh, she has stood five times in Batman and is now well-known there, lifting her party’s primary vote from 4.6 per cent in 1998 to 36.2 per cent in 2016 — well above the Greens’ Senate vote in Batman of 28.6 per cent. In Jagajaga, by contrast, the Greens’ vote in the House was barely higher than in the Senate.

The moral is clear: there are plenty of voters whose votes switch between Labor and the Greens depending on what they think of the candidates. As Peter Brent has pointed out, Feeney, the right-wing machine man and powerbroker, was the wrong candidate for Labor to run in Batman. Labor’s candidates in Northcote, the late Fiona Richardson and then Clare Burns at the by-election, were much better fits, and that is surely a big part of the reason why they polled much better than Feeney did.

I suspect Ged Kearney will recoup some of that Labor vote that drifted to the Greens in 2013 and 2016. It is quite possible that the change of candidate could swing several percentage points of the vote from the Greens to Labor.

As the Australian and the Financial Review never tire of telling us, federal Labor’s policies have also moved leftwards, partly to salvage their inner suburban seats. They have sharply narrowed the gap separating them from the Greens on tax avoidance, climate change, the Adani mine and, in particular, housing affordability and the growing inequality of incomes. The latter matters in both halves of Batman, including the half north of Bell Street, which is changing rapidly, but remains primarily working-class, and where the Greens have made fewer inroads.

And the Greens have shrunk from taking the initiative. On the issue on which they could most differentiate themselves from Labor — a humane policy on refugees — they have gone much quieter, fearing an electoral backlash on a wider front. Last weekend in the Age, Tony Wright wrote a memorable column on the deaths of three friends, reminding us how important it is to “seize the day” and, as his grandfather told him long ago, “don’t die wondering.” The Greens’ leaders should take that advice to heart.

The loss of Liberal preferences will hurt Labor. Last time they swung Batman its way, turning Bhathal’s lead of 3334 votes at the three-party stage into a Labor win by 1853 votes. That alone shifted 2.7 per cent of the votes into Labor’s column (relative to a 50–50 preference split). If no Liberal candidate stands this time, surely that will more than compensate for the gains Labor will make from replacing Feeney as its candidate?

Not necessarily. It will only do that if you assume that Liberal voters blindly follow the party ticket — and that, without it, they wouldn’t know what to do and would just vote randomly. Even in 2016, though, almost three in every eight Liberal voters ignored the how-to-vote card and gave their preferences to Alex Bhathal. In reality, Liberal voters this time will weigh up the options and make their own call. Those who prefer Labor will vote accordingly, as will those who prefer the Greens.

Remember: exactly the same thing happened at the Northcote by-election — and the loss of Liberal preferences there didn’t stop Labor gaining a 5.3 per cent swing from the 2016 federal vote. This election could surprise us all. ●