Does the Coalition have a problem with female voters?

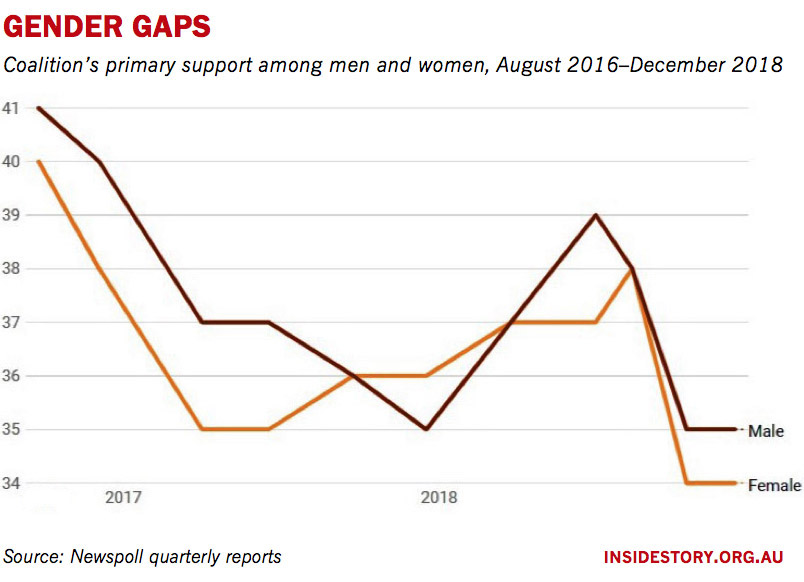

Newspoll’s detailed quarterly figures since the last election suggest a small one. From Pollbludger’s aggregated data (and ignoring Ipsos because of its small sample sizes) we get this graph covering the period from late 2016 to Decamber 2018. It shows more men than women saying the Coalition will get their primary vote, though the gap — usually rounding to 1 per cent — isn’t huge.

But opinion polls months or years before an election are one thing, and election results are another. The question “If an election were held today…?” is hypothetical in the extreme; unfocused minds are expected to snap to attention and pretend they’ve just endured a whole election campaign and are about to cast their vote.

Polling becomes more reliable as the election approaches, and during the campaign the question becomes “How will you vote on Saturday the such and such…?” Best of all are exit polls on election day. They need to be conducted before the votes are counted, or at least before the results are known and the airways, cyberspace and general chatter are filled with election takes and rapidly developing “hows” and “whys” about the outcome.

Over in the United States, with a population around thirteen times ours, they conduct lots of exit polls with a dozen or two questions and very large samples. Here, for example is the New York Times’s for the 2016 presidential election, with 24,537 respondents. In Australia we have nothing like that; instead, there’s a smattering of polls of varying quality, usually with no published gender breakdown, which are promoted on election day and never heard of again.

We also have the ANU’s Australian Election Study. Its strength is in its huge number of questions, its particular forte the same question repeated over the decades. But the long, time-consuming surveys (these days the instructions also include how to fill them in online), sent out by post, inevitably skew the respondent sample into, well, the type of people who are willing to devote an hour or so to such a project. And, crucially, the voting questions are let down by the fact that respondents fill in the survey in the days and weeks after they’ve cast their vote.

And then there’s Newspoll. It’s not an exit poll, but its final survey, conducted in the dying days of campaigns, is the next best thing. Even more than other pollsters, it puts extra resources into that last pre-election effort (after all, reputations can be made and unmade on that one survey), and so the sample size tends to be large by Australian standards. The 2016 survey, taken from the Tuesday to the Thursday evenings, had a huge 4135 sample, meaning probably around 2000 each for men and women.

Newspoll generally doesn’t publish those final-week gender breakdowns at the time, but they can be found later, in their regular quarterly tables, as entries for the most recent election. The latest Newspoll quarterly, for example, shows Coalition primary support of 39.7 per cent among women and 43.9 per cent among men in the final days of the 2016 campaign. Unlike the gap in subsequent Newspolls, that 4.2 per cent is worth noting.

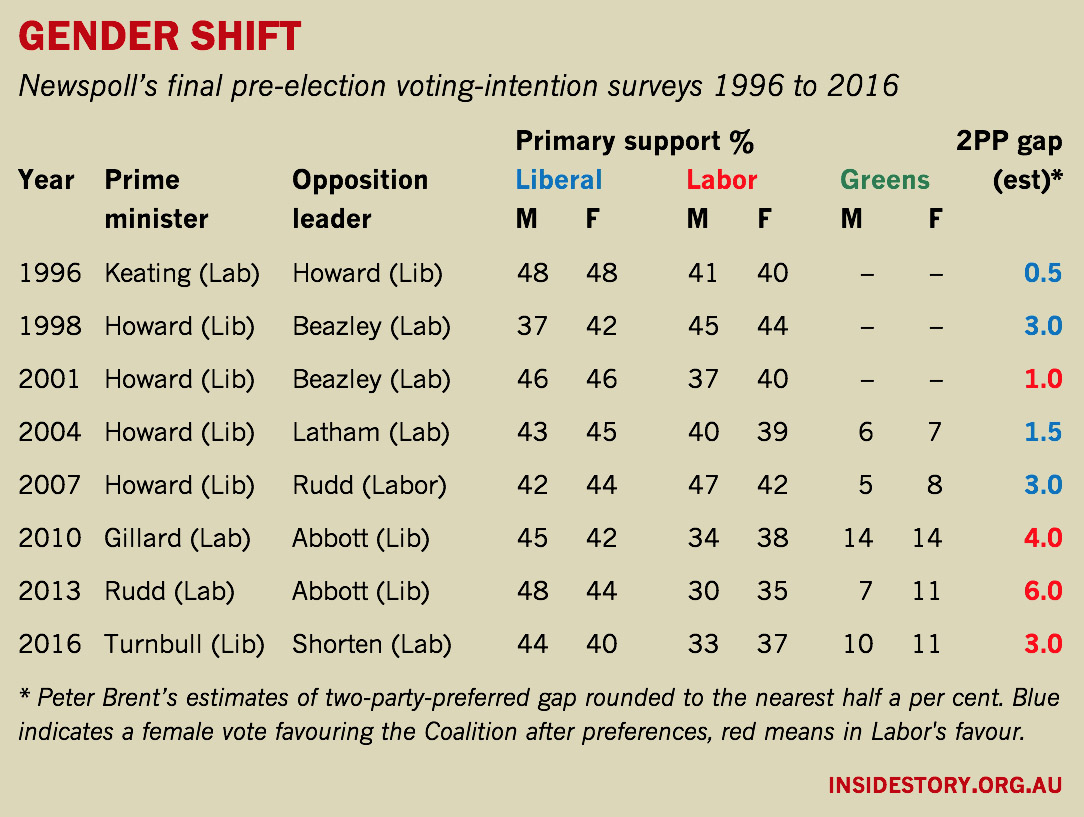

The chart below shows voting intention by sex from Newspoll final-days surveys over the two decades from 1996 (which is as far back as their published data goes) to 2016. (At the last two, Newspoll published to one decimal place.)

Yes, yes — insert caveats about margins of error and so on. And Tuesday to Thursday is not quite as good as Saturday.

One other thing: Newspoll doesn’t provide two-party-preferred numbers by sex (or age) because how minor party and independent preferences flow by such demographics is not known. For this exercise I’m rather recklessly assuming that men’s and women’s preferences flow to the major parties by the same proportions, which has enabled me to estimate rough two-party-preferred figures for each sex.

The estimated gap, rounded to the nearest half per cent, is shown in the last column, representing the difference between the female two-party-preferred vote and the male one. A red number means an advantage for Labor among women over men; and blue, an advantage to the Coalition among women over men.

For example, the 2016 figure of 3.0 per cent comes from an estimated Coalition win of 52–48 among men, and a Labor one of 51–49 among women.

What can we glean from these numbers? It seems the Coalition under John Howard, at least when it was in government, did relatively well with female voters, with 2001 being the exception. Given the closeness of the 1998 result, it’s reasonable to say that women saved the Howard government.

The two elections at which Kevin Rudd was Labor leader are a great contrast. In 2007 the Coalition enjoyed a three-point advantage among women, while in 2013 Labor had a six-point lead. The first contest was against Howard, the second against Tony Abbott. The first was Rudd as opposition leader, the second as prime minister.

Until 2016, the data (with that 2001 exception) was consistent with a possible “women back incumbent governments more than men do” thesis. But the most recent election also showed an advantage to Labor, even though it was in opposition.

(Actually, the Howard years were characterised, at election after election, by women moving towards Labor in mid-term Newspolls but then returning to the Coalition fold by the final campaign week.)

Of course, Abbott as Liberal leader is a variable in itself. In opposition it was often said that he had a “women problem,” but given the large overall opinion poll leads he enjoyed it might have made more sense to say he enjoyed a particular advantage among men. (And the other side of the equation was for most of that time, Julia Gillard as prime minister, also played a large part.)

In the end the Coalition romped in at the 2013 election despite that big six-point Newspoll gap (when men voted an estimated 56.5 per cent after preferences for the Coalition, and women 50.5 per cent).

But is voting support by gender a zero-sum game? Can a major party thrive by simply compensating for low support from one half of the population with high support from the other?

Surely not. Australian men, and society in general, are also increasingly “pro-women.”

For most of its existence the Liberal Party was more appealing to aspiring women MPs than the boozy, blokey Labor Party. The first female federal minister (Annabelle Rankin, 1966) and the first cabinet minister (Margaret Guilfoyle, 1975) were Liberals. (And in 1949 Robert Menzies had appointed Enid Lyons vice-president of the Executive Council.)

The roles have long been reversed, and in 2019 the Coalition’s parliamentary gender representation appears frozen in the 1990s. This is part of a general conservative grip on the Coalition parties on culture war matters, a hangover of the successful Howard years prolonged by Abbott’s success as opposition leader, and the less than glorious performances of his successors.

They see getting more women into parliament as just another trendy inner-city obsession, like climate change.

I wonder what the 2019 final week Newspoll gap will be. •