The federal government has paid nearly $80 million to buy the rights to water that mostly isn’t there but occasionally spreads out from the Balonne River, a tributary of the Darling in southern Queensland. The water, when it came, was being captured in vast private dams, and all the government can do now is hope that it keeps flowing downstream.

This is dubious enough, but it prompts the question: how have station owners been allowed to capture huge amounts of water like this, which the government then has to buy back?

The scale of the works in the Darling catchment is astonishing. This semi-arid northern basin is very flat, stretching for over a thousand kilometres, with river channels meandering whimsically, splitting up and joining again, sometimes terminating in wetlands. When a big rain comes, the water pours along floodways and over large areas of floodplain.

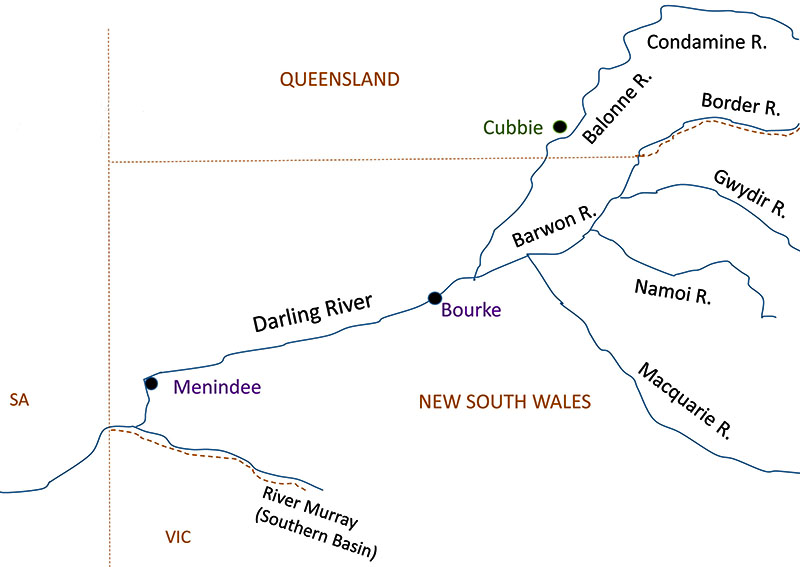

Above: the northern Murray–Darling Basin (not to scale)

Station owners have constructed embankments that can be thirty or forty kilometres long, to keep the water from moving to neighbouring properties or getting back into the main channel, and to direct it instead into their “turkey nest” storages. They have re-engineered the rivers.

A little further down the Balonne from the “Watergate” purchases, Cubbie Station has built diversion channels twice as wide as the river itself. Its storage covers 12,000 hectares, extends for tens of kilometres, and holds as much as Sydney Harbour. Cubbie takes 200 gigalitres a year on average, and up to 500 gigalitres — which is more than the Condamine–Balonne’s typical natural outflow of just 348 gigalitres.

Despite vociferous protests from affected farmers and communities, and despite some media exposure of what’s been happening — for example, in a report by Paul Lockyer for ABC’s 7.30 in 2004 — this sort of development has proliferated, fuelled by high returns from cotton.

Writing in 2000, journalist Phil Dickie reported that the amount of private storage had doubled in the previous two years. Controls were minimal: “an outdoor dunny can need more planning permission” than a storage hundreds of metres across with walls up to five metres high.

Dickie wrote of the cosy relationships between the cotton growers and the Queensland government, the willingness of officials to bend over backwards to interpret rules in the growers’ favour, and the years of court battles to squash any objections. The community around St George became deeply divided. Anyone trying to sort out the mess was moved on.

Where the water went: cotton farm dams on the Moonie River in southern Queensland. Rex Patrick

A similar frenzy of dam-building has taken place in northern New South Wales. In 2017 an ABC Four Corners report, “Pumped,” showed big irrigators with a horrible sense of entitlement telling reporter Linton Besser to get off their property — though he was actually standing on a public road they’d rerouted to accommodate their channel.

The program showed the same stark divisions in the community — enriched irrigators versus everyone else, who’d been left high and dry, feeling “beyond angry.” Clearly a lot of water was being stolen — meters had been tampered with, pumping was occurring when the river was too low — and as soon as water department officers began gearing up to take compliance action, their unit was disbanded.

Outright theft of water must be stopped, of course. So far, just one irrigator has been taken to court, which doesn’t look like a determined response. But that’s not necessarily how most of the water is being grabbed. Out-of-control floodplain harvesting has been compounded by obligingly light rules for pumping out of rivers — another way for irrigators to fill up their dams.

For example, just before the Murray–Darling Basin Plan went through federal parliament in late 2012 — the plan that was going to rescue all the rivers — New South Wales put out a new water-sharing plan for the Barwon–Darling. Heavily influenced by the cotton growers, it actually loosened the regulations they were subject to. Additional A Class licences were issued, which allow pumping when river flows are low; these licences could now be used with huge pumps instead of ones limited to 150 millimetre pipes; and 300 per cent of a licence volume could be pumped out at any time over three years.

This opened the way for irrigators to pump lots of water into their dams using A Class licences saved up for this purpose, at times when flows were very low. They kept their ordinary licences for years when flows were higher.

Licences could also be traded. When, under the Basin Plan, the Commonwealth bought licences for the environment, more water was left in the rivers as a result, but this just meant there was more for the remaining irrigators to take.

Soon, nearly three-quarters of the water was in the hands of two big players, Webster Ltd and the Harris family. And the Darling kept drying up.

NSW farmer leader Mal Peters told Four Corners that most Australians supported a large amount of money being spent to fix the river. But “if the outcome of it is that we have a very few number of irrigators that have got a huge windfall out of this, I think everybody will be disgusted.”

Investigating the reasons for the massive fish kills down near Menindee over summer, both scientific panels — the Academy of Science one set up by the opposition, and the Rob Vertessy one set up by the government — could see it wasn’t just drought that had caused the Darling to dry up. The catastrophe was partly the result of human activity. But to what extent, neither could say.

The southern basin — taking in the Murray, Murrumbidgee and Goulburn — is comparatively regularised. But in the northern basin somewhere between half and three-quarters of the water taken is not metered. Nor is there any credible model of the system to explain what’s happening. The recent SA royal commission on the Murrary–Darling Basin was scathing about the slowness to act.

Just how laggardly governments have been is illustrated by New South Wales’s proposal last year for monitoring floodplain harvesting. This relies mainly on old-fashioned “gauge boards,” painted with water levels, to be read each day by the irrigators themselves, and audited just once every ten years.

The first big step towards saving the Murray–Darling came with the decision to cap diversions at 1994 levels. Since weather and water availability varies from year to year, a valley’s cap is not the same every year, but rather the volume that a model shows would have been diverted in that year if there was no underlying increase in diversion.

The Barwon–Darling went over its cap every year between 1997, when compliance started, until 2011. Then New South Wales changed the model, so it was always under. Meanwhile Queensland’s original caps were based on the diversion level at 2000 rather than 1994, since the state “started late” and was allowed a few years to “catch up” — which it went at with gusto.

The Basin Plan establishes new, lower caps by identifying diversion levels in 2009 and then specifying how much these levels must be reduced by retrieving water from irrigators. Baseline diversions for the northern basin have been determined to be 3812 gigalitres, nearly 1000 gigalitres more than the original caps, since things like run-off dams are now included.

Only 207 gigalitres of this is for floodplain harvesting. Yet this figure is now acknowledged to be a gross underestimate. Private storages along the Condamine–Balonne alone are thought to have total capacity of over 1500 gigalitres.

The SA royal commission was told that the Murray–Darling Basin Authority proposes, when it finally has a proper handle on the amount of floodplain harvesting, simply to use the new amount to increase the baseline diversions. So then the new caps will likewise be increased. There’d be precious little assessment of environmental requirements in that approach.

Even amid this scrambling to sort out what water is being taken, the new caps have been softened. The Basin Plan said 390 gigalitres should be returned to the environment, subject to a review. Last year, after a lengthy, controversial review, the Authority proposed this be changed to 320 gigalitres. Federal parliament baulked at first, then let it through.

The argument was that this was the price that needed to be paid for better protection of low flows. But governments have every right to protect low flows. It seems they feel that they have to tiptoe around the cotton growers.

Governments may not have much of a grasp on how much water is being hauled out of the Darling basin by irrigators. But anyone can tell it’s a lot just by looking at aerial or satellite photos showing multiple private dams containing water, right at the time the fish were dying.

And the wide expanse of cotton is there for everyone to see. Despite the current drought, over 100,000 hectares have been planted this season. In the order of 1000 gigalitres will be applied to this crop, and a further 1000 gigalitres is likely to evaporate in private dams. In the meantime, only forty gigalitres has flowed past Bourke in all of 2018.

Analysis by the Australia Institute shows cotton production stays reasonably high for as long as five years after the Darling has started to dry up.

Irrigators themselves are very aware of what is happening. They know that less water is reaching the main Barwon–Darling; they are happy to sell their water entitlements there to the government at high prices, then concentrate on their holdings in the top of the catchment, making sure even less water gets to the bottom.

People have given up expecting reliable water in the lower reaches of the Darling. Broken Hill used to get its water from the Menindee Lakes, but now $500 million has been spent on a new pipeline so it can get its water from the Murray, three times further away.

Also relying on the Menindee Lakes, Tandou was at one time a thriving irrigation enterprise with permanent plantings like vines. Then it switched to cotton and grain, growing a crop every couple of years. Not long after taking Tandou over, Webster Ltd sold its water to the Commonwealth. It was paid $38 million for the water — “ghost water,” as it was described by one experienced observer — and $40 million as compensation for having to restructure for dryland farming.

A wonderfully sweet deal. The sort of deal, like the “Watergate” ones, you’d expect Barnaby Joyce to approve of. Wait on — he was the minister then too, so he did.

The bigger scandal, though, is that so much water has been allowed to be extracted from the basin in the first place.

It’s a very long way from the days when paddle steamers plied their trade up the Darling to Bourke and beyond… when the river accounted on average for 17 per cent of the flows in the Murray. The Murray is a worry, certainly, but what is absolutely clear is that the next water minister needs to throw him or herself into reversing the destruction of the Darling. •