Last week, former prime minister John Howard played down the Liberal Party’s hammering in the Victorian election by describing the state as “the Massachusetts of Australia.”

In the American parlance, Massachusetts is a deep Democrat blue. It was the only state not to vote for Richard Nixon in his landslide re-election victory in 1972 (a fact that, with the benefit of hindsight, might reflect uniquely good judgement). When American think tank Data for Progress modelled state-by-state support for progressive policy ideas using a combination of polling and demographic data, Massachusetts unsurprisingly polled well. Support for policies like a federal jobs guarantee for all Americans, extending public healthcare to cover all citizens rather than just over sixty-fives, and paid family leave to cover childbirth and medical emergencies runs between 60 and 70 per cent.

The interesting thing isn’t that Massachusetts supports these ideas — it’s that Massachusetts is far from alone. “Medicare for all” registers majority support in a total of forty-two states, including Texas, Florida, Ohio and Indiana. Expanded family leave is supported in all but one — Wyoming (where support runs to 48 per cent). And the biggest idea, a federal jobs guarantee, is stunningly popular, with majority support in every state, from “ruby red” West Virginia (62 per cent) to California and New York (71 per cent).

Victorians do support big-picture policies but, like their counterparts in Massachusetts, this doesn’t make them outliers — they are both in good company.

What do Australians want?

It’s hard to find a common thread through the political wreckage of the post-Howard years. If there is one, it might be this: Australians expect their governments to take responsibility and deliver results. And over the past decade they have been disappointed. No Australian wants the farcical bickering over other people’s lives that ended the federal parliamentary year yesterday.

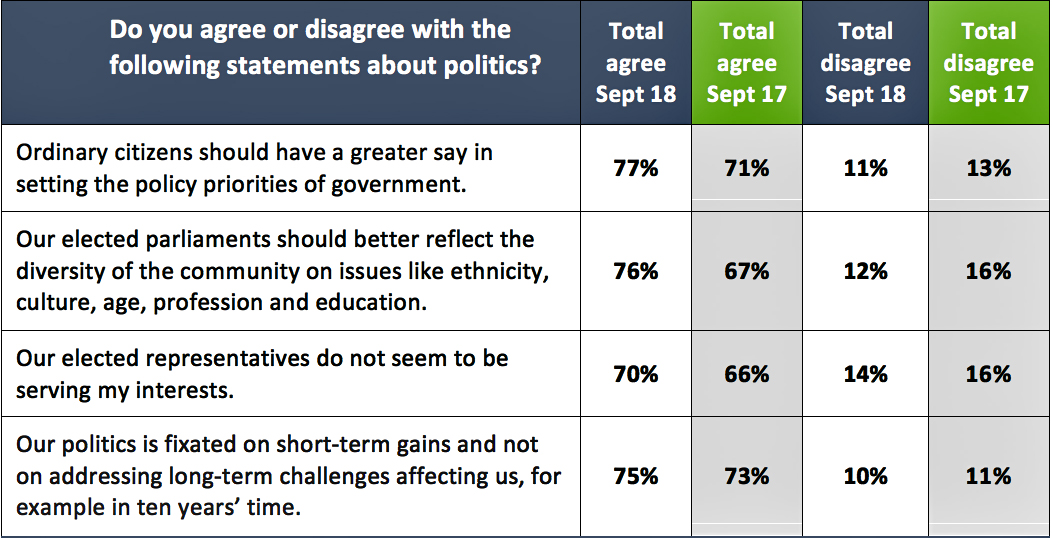

Our research reveals a staggering and growing gap between what Australians want and what their government is delivering. More than two-thirds of Australians don’t think their elected representatives act in their interests. An even larger proportion perceive fundamental problems with how our system of government works in practice: three-quarters say that ordinary citizens should have a greater say in policy, that politics is fixated on short-term issues instead of long-term challenges, and that parliaments should better reflect community diversity on ethnicity, culture, age, profession and education.

Source: CPD attitudes research conducted by Essential in September 2017 and September 2018 of 1025 and 1030 respondents respectively.

Similar views have been reflected in other Australian studies, including the latest Scanlon Foundation Mapping Social Cohesion Survey released this week. Since 2009, respondents have consistently identified “the quality of government and political leadership” as the second or third “most important problem facing Australia today.” This year only 29 per cent of respondents believed they could trust the government “almost always” or “most” of the time.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to Australia. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index shows a decade of “democratic recession” worldwide. But while this trust deficit is something we share with the rest of the world, there is a strong ray of hope at home. Our research suggests something distinctive about how Australians view their democracy. It’s a matter of what they think the primary purpose of democracy is.

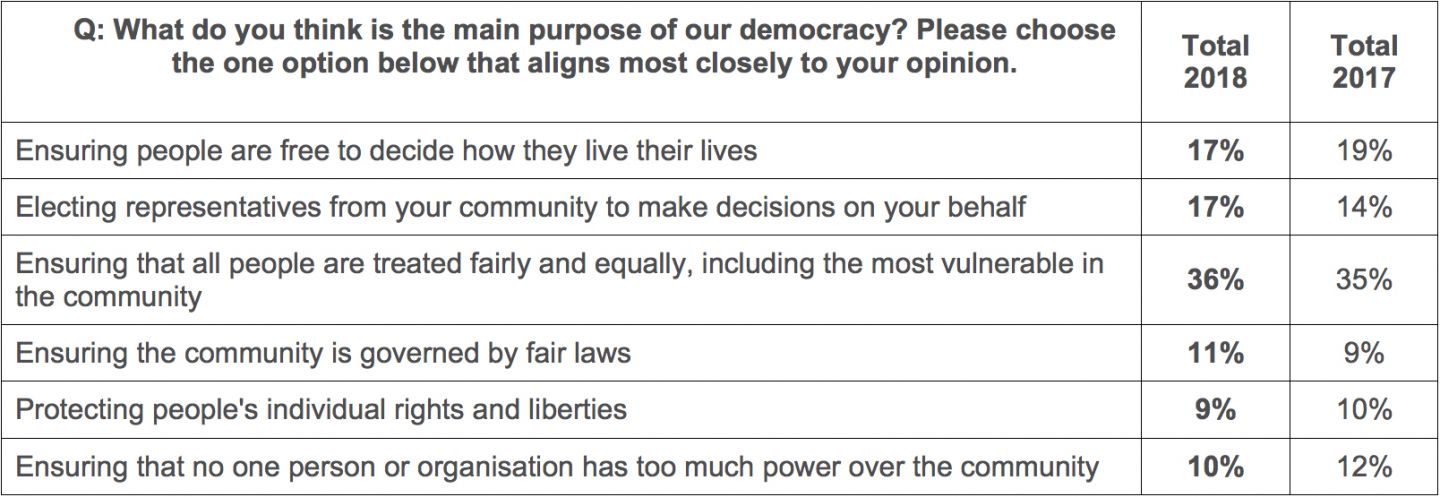

Surveys in the United States and Britain show that their citizens tend to see the processes that underpin their political systems (free elections, representative political institutions) as the most important aspects of their democracy. Australians, on the other hand, or at least a sizeable chunk of us, are more focused on the quality of the outcomes. When we asked Australians what they thought was the main purpose of democracy, the response twice as popular as any other was “ensuring that all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable in our community.”

Source: CPD attitudes research conducted by Essential in October 2017 and October 2018 of 1025 respondents each.

This result is significant: it means many Australians want their democracy to be purposeful — about ends, not just means. They want their democracy to be bold, with government as an active and effective partner. And they want a fairer society where all Australians can live flourishing lives.

Victoria’s election was carried by a government that took an unapologetically forthright role in providing infrastructure, enhancing key public services, and tackling important social and environmental issues. This sort of agenda is popular, and open to parties and political leaders of all ideological stripes, but not everyone has got the memo. (In Massachusetts, five of the last six governors have been Republican. The Victorian Liberal Party, out of government for all but four of the last twenty years, should be so lucky.)

This is not to say that Australians don’t also want substantial reforms to the way our democracy works. Surveys show significant majorities favouring big changes to institutions and processes, including fixing federal–state relations, establishing a national anti-corruption commission, moving to four-year parliamentary terms at the national level, embedding the public sector in more parts of Australia, and putting citizens on parliamentary committees.

The business of business

Government is only part of the story: trust in business is also on the decline. The banking royal commission has shed light on serious misconduct in our financial system, where the customer was often all but forgotten as institutions chased short-term profits for their shareholders. As NAB chair Ken Henry said in his testimony last week, “the public tolerance of that model of accountability has been pretty well eroded to zero.” For Henry, that is the “principal reason” for “a loss of trust in business.” In his view, boards should be accountable “to the country, and for the country’s future,” not just to shareholders.

This is a debate that started after the global financial crisis but has not gained much traction in Australia. Should corporations only act in the interests of shareholders, or should they have a broader purpose? Should we be satisfied with rent-seeking from some major corporates, as opposed to genuine value creation and the appetite for risk it requires? Our research suggests Australians expect businesses to uphold their end of the social bargain, with a clear majority favouring a model that places long-term social impacts on par with profits and productivity. Far more people believe it is “very important” for corporations to make a positive contribution to society than believe they exist simply to create value for shareholders.

There are some encouraging green shoots here. Some leading Australian companies are taking climate change and sustainability more seriously, driven by mounting pressure from regulators, institutional investors and shareholder activists — as well as a more enlightened view of their social licence and self-interest. But, like government, business has a long way to go to get back in step with community attitudes. The recent revelations from the royal commission, and the spectacle of revolving door politics in Canberra, can hardly be helping to overcome the sense that our leaders in both fields lack a sense of wider moral purpose.

Rebuilding confidence

There’s no easy way to restore people’s faith in government, but a good place to start is to restore government’s faith in itself.

As complex policy challenges have been piling up, governments have been stepping back. We are all familiar with the narrative that has guided public administration over the last several decades: the best thing the public sector can do is to clear the field. Government services have been outsourced, creating immense new markets, and profits, for private providers. Major assets and utilities have been sold off, often in a way that has allowed private operators to corner lucrative, uncompetitive markets. Responsibility and accountability have been dissipated.

Headcounts don’t tell the whole story, but the public service workforce Scott Morrison inherited when he became prime minister was 5 per cent smaller than it was in the last year of John Howard’s administration, and 10 per cent smaller than at its 2011 peak. Recent staffing and funding cutbacks have been indiscriminate. Agency staffing and budgets have been squeezed, and expertise contracted in at great expense. Over the five years to 2017, government work generated $1.7 billion in revenue for the Big Four accounting and consultancy firms. Along the way, the creeping politicisation of public service appointments has served to undermine independent advice.

Belief in government capability isn’t merely an academic issue. How can we expect people to trust that the CSIRO is ready to produce Australia’s next scientific breakthrough, or that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission is properly policing corporate misconduct, or that the Tax Office can crack down on tax avoidance, when governments won’t provide agencies with the resources they need to do their jobs? Even the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet’s submission to the inquiry into the use of consultants and contractors said that “with the implementation of staffing caps in the Australian Public Service, agencies have more frequently needed to engage external contractor and consultancy services to fill key roles.”

If this model were delivering the goods, all this might be fine. But the poor results — not least in Jobactive, vocational education and training, and aged care — have undermined public trust in government. Procurement-based policy has become a poor substitute for experience-based service design and delivery. According to our research, three-quarters of Australians think it’s important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver social services directly rather than pay private companies and charities to deliver them. Fewer than one in ten think this is not important. What’s more, Australians rate services delivered by government as more accessible, more affordable, of higher quality and easily more accountable than those delivered by private companies and even by charities.

This shows there is a real opportunity to turn this vicious cycle into a virtuous one. The big policy opportunities of our time — the issues where the public is crying out for better outcomes — are precisely those that require a more creative, constructive role from governments. Governments shouldn’t be afraid of thinking big. In fact, it is only in doing this that we can effectively turn the complex challenges of twenty-first-century life into benefits for Australia. These could include harnessing a technological revolution in energy and transport to drive clean jobs and economic development; rebuilding government systems and services for a data-driven but human-centred age; reshaping business and finance to be genuine drivers of long-term value; managing the impact of an ageing society; and reinvesting the fruits of our material prosperity into the things we value most, including health, learning, meaningful employment and protection of our environment.

Given all these potential benefits, you could be forgiven for asking: why aren’t governments already working on this? The short answer is that in many countries, including Australia, they are. But in most cases, they’re doing so within a paradigm that undermines policy ambition and undercuts governments’ ability to deliver. This makes the downward spiral of trust and capability even harder to arrest.

Governments promise agility and opportunity but struggle to deliver. Innovative programs and funding commitments are only one budget measure or ministerial reshuffle away from the scrapheap or the pork barrel. We prosecute an Australian ideas boom while those on the losing end of the disruption “bargain” spend hours trying to get through to Serco-staffed Centrelink call centres. We announce trials but fail to consolidate the evidence of what works. Is it any wonder people have lost faith?

Missions not half-measures

To rebuild the faith in government that people are craving, and to give government the confidence to take on the big challenges, we first need to change our mindset about what governments can do. Policy-makers could do well to listen to economist Mariana Mazzucato when she visits Australia next week. In a trio of books, Mazzucato powerfully and provocatively articulates things we forgot we knew: that government research and investment have historically been key drivers of wealth creation and innovation, including in Silicon Valley; that growth has not just a rate but a direction; and that the contours of long-term development have always been shaped by policy and strategy, or their absence.

For Mazzucato, a big part of the problem is that governments have internalised the prevailing narrative about their own limitations, and as a result have become “hesitant, cautious, careful not to overstep in case [they] should be accused of crowding out innovation, or accused of favouritism, picking winners.” The story matters: “we need a new vocabulary for policymaking,” she says, that can reduce the timidity which has for decades kept politicians from funding big-picture investment.

Mazzucato wants to push our current thinking about the role of government beyond the usual one of fixing market failures: “It is about shaping a different future: co-creating markets and value, not just ‘fixing’ markets or redistributing value. It’s about taking risks, not only ‘de-risking.’ And it must not be about levelling the playing field but about tilting it towards the kind of economy we want.” As shadow finance minister Jim Chalmers said last year, citing Mazzucato, this isn’t about dismissing “the power of markets” but about “directing economic growth towards an intelligent, sustainable and inclusive model.” Australia’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation, or CEFC, is a standout example of this strategy in action, where the private and public sectors “nourish and reinforce each other in pursuit of the common goal of economic value creation.”

But the scale of our ambition can go well beyond that. Mazzucato urges governments and industry to identify core “missions” where catalytic, value-creating roles are most readily within our grasp — and go for them. What might this look like? Well, the CEFC could be seen as a down payment on a “Green New Deal” that puts zero carbon and renewable energy right at the centre of Australia’s strategy for employment and economic development. We could have missions for Australia to be a net exporter of renewable energy; build cohesion and multiculturalism through the world’s best settlement services; provide universal access to early childhood education; be a custodian of the rules-based international order; preserve our greatest natural assets like the Great Barrier Reef and the Ningaloo Reef; and drive extinction rates of native plants and animals to zero. All of these are worthy goals. All would be popular. All would have wide spillover benefits. And all are examples of where our current approach is failing to deliver and, in so doing, is eroding our collective faith in our system.

Such a shift in thinking would face a familiar critique: that more government intervention means more corruption and more inefficiency; that picking winners in the marketplace really means picking losers; that well-meaning attempts will crowd investment out rather than crowd it in. These are real risks that we’ve been hyper-attuned to over decades while policy capacity and purpose has atrophied. Mitigating these risks requires an excellent public service. Without this expert, engaged public sector, we run the even greater risk that events will set a direction of their own, and lead to disaster. Again we can take our cue from Mazzucato, who says, “The economy can indeed be made and shaped — but it can be done either in fear or in hope.” Hope isn’t enough on its own, but it is a far better starting point.

Our vision splendid

The late Indigenous activist Tracker Tilmouth was fond of Banjo Paterson’s reference to a “vision splendid” in his famous poem “Clancy of the Overflow,” and frequently asked people what their vision splendid was. Which vision splendid can we use to guide us in rethinking government?

Of course, a new Australian vista won’t be delivered overnight — the thunderstorms of the past decade are still clearing — but David Thodey’s current review of the Australian public service, running alongside the banking royal commission, provides a perfect launching pad for some big ideas on rewiring government and finance.

There are several opportunities that government could grasp right now to get things moving in the right direction.

The first is to invest in the ability of the public sector to fulfil a more dynamic and demanding role. This is in Thodey’s domain: he has signalled his panel’s desire to think big, and over 700 submissions have risen to that challenge. It will take time for the next government to review the findings and plan implementation of the most important reforms, but what it should prioritise are the investments and capabilities that will support a more innovative, mission-led approach to the public sector’s work. These might include new approaches to project evaluation and a move beyond static cost–benefit metrics that discount long-term benefits and underplay the dynamic role the state can play in shaping new markets, services and technologies. It might feature new forms of public–private partnerships, with government playing a more active role as a lead investor and risk-taker, and taking a correspondingly larger stake in any upsides from successful investments. It might also include investment in experience-based policy design and service delivery at the local level.

Above all, however, Thodey must reinforce the need for the public service to be funded and empowered to think for itself in a way that extends our horizons and brings policy development closer to the people. Without that independent heft, Australia and its governments suffer. It isn’t enough, as Mazzucato has written, “to talk about the ‘entrepreneurial state’; one must build it — paying attention to concrete institutions and organisations that are able to create long-run growth strategies and ‘welcome’ the inevitable failure this will entail.”

The second opportunity is to appoint an Australian Sustainable Finance Taskforce. Over the past two years, government-appointed panels in the European Union, Britain, Canada and elsewhere have produced far-reaching policy road maps for receptive governments that are looking for ways to support more sustainable, socially aligned financial systems. Australia has an immense amount to gain by replicating a similar approach here, given the size and sophistication of our financial sector and its endemic issues with governance, culture and trust laid bare by the royal commission. Joining the global conversation on new taxonomies and standards for sustainable financial products and projects is the bare minimum for ensuring the next generation of trade and investment opportunities do not pass Australia by.

Ultimately, the ambition should be to reorient finance to better serve the long-term objectives (as well as manage the short-term needs) of societies that the sector serves. A government-backed Sustainable Finance Taskforce that crystallises the early efforts of industry and regulators to lead this conversation won’t provide the last word, but it would be a practical, principled first step towards a system that is more aligned with the real drivers of long-term value.

The third opportunity is to engage fully and respectfully with the enormous chance for democratic innovation provided by the Uluru Statement from the Heart, produced as it was by those who had come from across our sunlit plains “from all points of the southern sky.” This is where the vision splendid for Australia can start in a way that empowers all Australians, from first to last.

The bigger task — piecing together the capabilities and coalitions needed to bridge the trust deficit and set out on missions to tackle those areas where our country falls short — is not for the faint-hearted. The pace of change and the magnitude of the challenges ahead are daunting for the public and policy-makers alike. There is always the risk of failure, but we can’t let that stop us. We need to rebuild confidence that we can take on even the biggest of challenges. As the most famous Massachusetts politician of all time put it when he was laying out NASA’s mission to land a man on the moon: “It is not surprising that some would have us stay where we are a little longer to rest, to wait.” But Australia, like the United States that president John Kennedy was referring to, “was not built by those who waited and rested and wished to look behind them.”

In our increasingly complex world, we need to broaden our view of what government can achieve, and build a vision splendid that is uniquely Australian. It is precisely this new mindset that could spark a fresh era of development for a confident, smart nation of compassionate and sustainable communities engaged with each other, their region and their world. •

Mariana Mazzucato is visiting Australia as a guest of the Centre for Policy Development.