The reality is that the Labor Party has secured an average or conventional swing in a by-election to it in Longman and has not secured any swing at all in Braddon. At this stage it looks like it will be a lineball result. So there is not a lot to celebrate for the Labor Party. There is certainly nothing to crow about.

— Prime minister Malcolm Turnbull, Sunday

Malcolm Turnbull tells us every day how much he dislikes lies in politics, so we wouldn’t want to suggest that the PM is lying about this. Let’s be charitable and assume that he just doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

He’s hardly alone in that right now. I’ve lost count of the number of commentators who have told us that a “normal” by-election swing is 5 per cent to the opposition. That might be true if your “normal” by-election is in a government-held seat. But it’s certainly not true for by-elections in opposition-held seats — as all of Super Saturday’s by-elections were.

They are very different. First, governments rarely contest them. In the past thirty years, before Saturday, there had been nineteen by-elections in seats held by the opposition — but the government of the day contested just two of them. And when they did contest them, the swings went either way.

Since Federation, until Saturday, there had been just sixty by-elections in opposition seats. In half of those, the government of the day didn’t contest the seat. In another one, it hadn’t contested the previous election, making it impossible to estimate a swing.

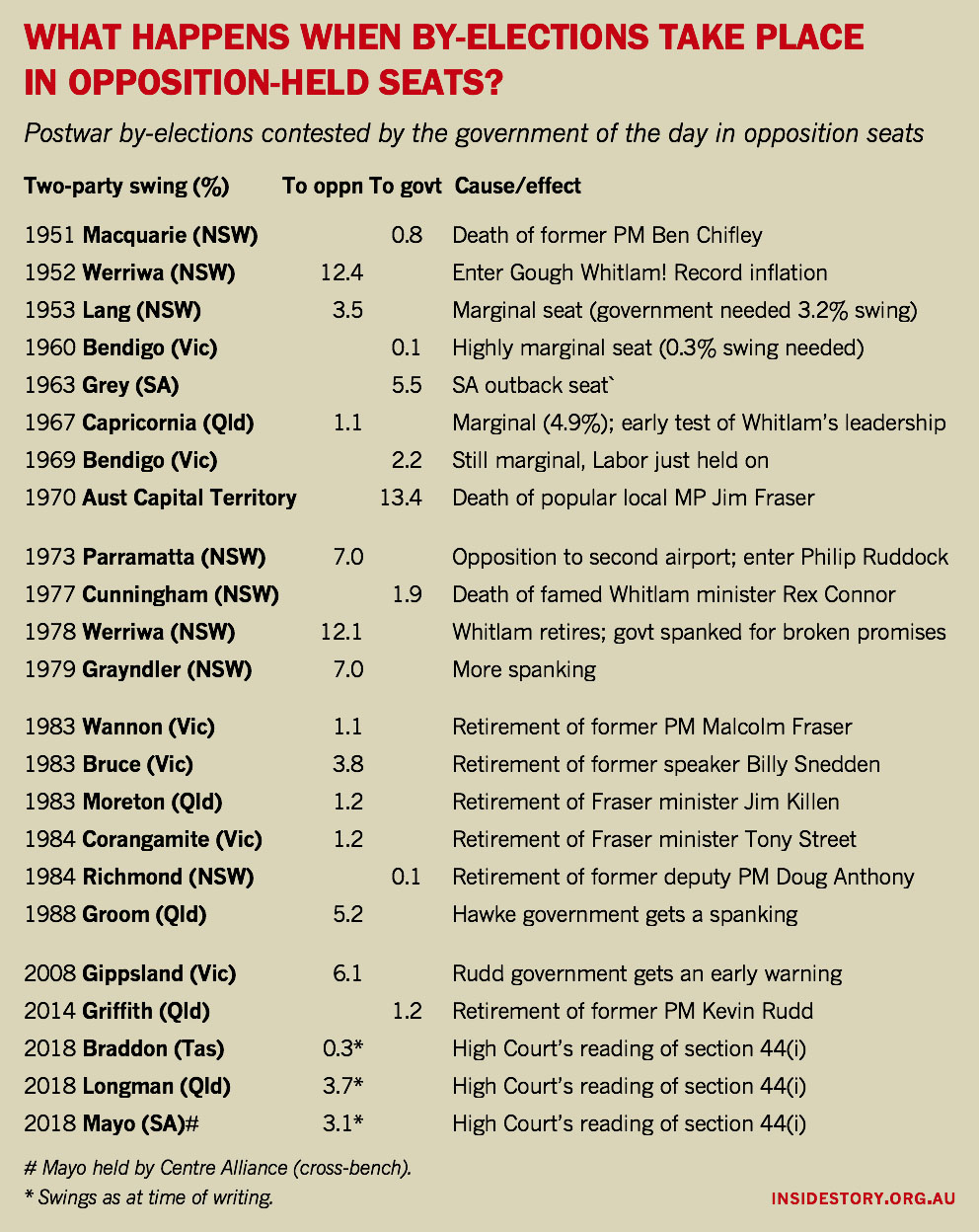

There have been just twenty-nine contests where a two-party swing can be estimated, and they have produced wide-ranging results. But until Saturday, the average swing to the opposition in by-elections in its own seats was just 1.5 per cent.

Fifteen by-elections recorded swings to the opposition. Fourteen by-elections recorded swings to the government. Some swings were very large, in both directions, but most were small. Even in the past thirty-five years, when resignations replaced deaths as the main cause of by-elections, the median swing to the opposition was just 1.2 per cent.

Yes, it is true that governments have won seats from the opposition only twice: in 1904 and 1920. But of the thirty contests the government sat out, the opposition lost three of them to other parties or independents — including Labor losing Cunningham to the Greens in 2002, and the Nationals losing Lyne to Rob Oakeshott in 2008. That’s recent history that underlines how vulnerable any seat-holder can be at by-elections.

My source for all this is the wonderful database of election results amassed by psephologist extraordinaire Adam Carr, on his Psephos website. That is supplemented by a useful Parliamentary Library paper, “House of Representatives By-elections: 1901–2017,” by researcher Stephen Barber.

The estimates of the swing at each by-election are Adam Carr’s, at least until the 1980s, when Hawke government minister Robert Ray made it a rule that all preferences should always be counted.

Carr’s data shows there is a very clear difference between by-elections in government seats and those in opposition seats. Stephen Barber estimates that between 1949 and 2017 the average swing to the opposition in government seats was 4.7 per cent — roughly the swing recorded against John Alexander in last year’s Bennelong by-election.

By-elections in opposition seats are sometimes like that, if voters use them to give the government of the day a spanking. As the panel below shows, six of the twenty postwar by-elections of this genre have recorded big anti-government swings. Gough Whitlam rode a 12.4 per cent swing when he entered parliament at a by-election in Werriwa in 1952, when the Korean war wool boom and wage indexation sent inflation soaring above 20 per cent. In 1973, as prime minister, he copped a 7 per cent swing in the Parramatta by-election against his government’s plan to site Sydney’s second airport directly north, at Galston. And when he retired from politics in 1978, Labor won another 12.1 per cent swing as the electorate punished the Fraser government for brazenly breaking its election promises.

But these are the exceptions, not the rule. In our times, if the government fears a bad reception, it doesn’t stand a candidate. This began with Menzies, but the Liberals set a new record on Saturday by refusing to stand even in Perth, which Labor held last time by just 3.3 per cent.

To state what should be obvious: if the government was expecting a swing of 5 per cent against it, or even 3 per cent, it would not have stood candidates in Braddon, Longman or Mayo. It contested these seats because it thought it could win them.

It delayed the elections for three months until a date it thought was ideal for its chances: the weekend on which Labor was scheduled to hold its national conference. Turnbull told us they were a referendum on Bill Shorten’s leadership: he didn’t say that because he thought it was a referendum Shorten would win.

The swings against the government after preferences in these three seats, on current counting, average 2.4 per cent. If that doesn’t sound like much, remember that all three saw huge swings against the government in 2016: 4.8 per cent in Braddon, 7.7 per cent in Longman and 17.5 per cent in Mayo. The Liberals were expecting to win some of that back. Instead, they lost on Saturday by even more.

And in Longman, they benefited this time from a larger One Nation vote, with a how-to-vote card preferencing them instead of Labor. I have pointed out before that the vast majority of One Nation voters do as they please on preferences, but One Nation’s 16 per cent of the vote should have swung another 1.5 per cent or more to the Liberal National Party. The 3.7 per cent swing recorded on current figures masks an underlying swing against the government of more than 5 per cent.

Why does that matter? Well, the Turnbull government is in power because it won a lot of seats in Queensland in close contests.

Eight of its seat there are held by margins of less than 4 per cent: on Antony Green’s calculations post-redistribution, Capricornia (0.6), Forde (0.6), Flynn (1.0), Petrie (1.6), Peter Dutton’s seat of Dickson (2.0), Dawson (3.3), Bonner (3.4) and Leichhardt (3.95).

The government is already going into the next election two seats down as a result of the redistribution in Victoria. It can’t afford to lose significant ground in Queensland. As things stand, this by-election result suggests it will.

So Turnbull and his ministers are turning to the task of changing the way things stand. There will be no company tax cuts for the top end of town, even if Derryn Hinch’s proposed compromise is adopted. That money could be redirected to something electorally popular: perhaps bigger personal tax cuts, perhaps more health spending — perhaps even making its claims of record infrastructure spending a reality, rather than using them to cover up a diminishing infrastructure spend ahead.

Who knows, the Coalition and its media entourage might even abandon their incessant campaign to persuade Australians that Bill Shorten is too awful a person to be entrusted with the job of prime minister. I have made my criticisms of Shorten clear, but as someone (I think, Laurie Oakes) put it once, Turnbull has a tin ear. Voters do not love Bill Shorten, but they don’t see him as an ogre, and they switch off when the Liberals and their media supporters try to depict him as such.

It is sad to see Turnbull, who once stood for something better, engaging in gutter politics, avoiding any hard decisions — especially on climate change, where his government has now effectively abandoned Australia’s pledge under the Paris agreement — and relying on rosy forecasting to hide the still-parlous state of the budget the Coalition had promised to fix.

Malcolm, if I may, one piece of advice. The people you have lost are broadly those in the political centre. They are looking for the values you promised to bring to politics: adult conversation about issues; an end to mud-slinging and personal attacks on opponents; respect for truth and objective facts; respect for people; and willingness to look ahead, plan for the long term and explain the issues to voters.

That is the new politics they thought you would bring to replace the thirty years of leaders who tried to divide us and rule. The election must be held by May. You have nine months to regain the goodwill you have squandered since 2015. ●