ON Saturday 18 December Michael Somare Jr, the son of Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, went to the home of the governor of the East Sepik Province, Peter Waranaka, in Wewak. During a dispute over what a police officer described as “a range of issues from politics to administration,” Somare drew a shotgun and aimed it at Waranaka. A senior East Sepik administrator standing nearby struck Somare’s arm and the shot missed its target. It was the most dramatic of a series of events in Papua New Guinea that have intersected and had their impact on national politics.

The incident in Wewak set in motion two processes to resolve the dispute and punish the guilty. The first is formal: the police arrested Somare Jr, charged him with attempted murder and released him on a surety of K1000 – a small amount, equal to about A$350, but there was not much chance of Somare fleeing the province and the country.

The second process involves “traditional” compensation. It is tradition distorted by district, provincial and national politics, by cash, by who has the power to exploit and intimidate and by escalating precedents set elsewhere. Sir Michael Somare went to Waranaka’s house and offered two pigs and K20,000 or K30,000 (reports of the amount varied) in cash, asked that neither side resort to violence and said that his son would be treated before the court like any other citizen. Waranaka and his supporters rejected the offer and demanded K5 million.

Provincial governors in Papua New Guinea automatically become members of the national parliament, so Waranaka is also the member for the electorate of Yangoru-Saussia. In addition to his political base, Waranaka has the support of “high profile criminals,” according to rumours, who have arrived in Wewak in case there is violence between Somare supporters and people from Yangoru. It is not clear whether Waranaka has or wants the backing of “high profile criminals” or, indeed, that such a group arrived in Wewak. Regardless, the two processes, formal and traditional, are continuing.

Succession and its discontents

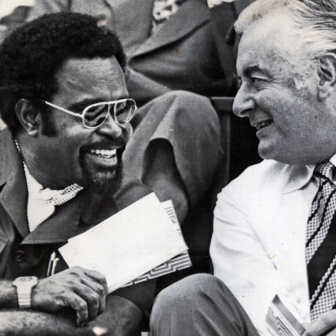

Sir Michael Somare is the elected member for the East Sepik Province, which includes Yangoru-Saussia. First elected to parliament in 1968 and prime minister of Papua New Guinea when it gained independence in 1975, Somare retained office until 1980 and returned to the prime ministership from 1982 to 1985. He was elected prime minister again in 2002 and re-elected in 2007, confirming his place as the key political figure in Papua New Guinea over the past four decades. But Somare is now seventy-four, and his age, health and accumulating political problems mean he might not stand at the next scheduled election in 2012.

Speculation about the succession and manoeuvring for advantage are intense, and involve the extended Somare family. Arthur Somare, the second-oldest son, is the member for Angoram, another East Sepik seat in the national parliament. Having held several ministries, Arthur is now Minister for Public Enterprises and plays a leading role in the multi-billion-dollar ExxonMobil liquefied natural gas project and in the National Alliance, the strongest party in the coalition that sustains Sir Michael in government. Arthur has long been fighting to delay court investigations into claims he has engaged in official misconduct. He is often mentioned as a possible successor to Sir Michael, but is not considered among those most likely to succeed him.

Bertha (sometimes Betha), the oldest of the Somare children, is head of the prime minister’s media relations unit. She has been a defender of and spokesperson for the prime minister and at times has been said to announce changes before they are known to the relevant ministers. Another son, Sana, lives in Singapore and a daughter, Dulcie, in Australia. Michael Jr, meanwhile, runs the family construction and engineering business in Wewak. Should Sir Michael be succeeded as prime minister by an opponent, that could be detrimental to the extensive political and business interests of this next generation of Somares.

In the reports on Somare Jr’s alleged attempts to shoot Waranaka, Sir Michael is variously said to be the “sidelined” or “stood down” prime minister. To explain that status requires the telling of three other unfolding stories: the Ombudsman Commission investigation into Sir Michael’s annual returns, the replacement of one deputy prime minister with another, and the repeated attempts to appoint a governor-general.

Sir Michael stands down

For several years Sir Michael (like Arthur) has been taking court action to prevent the Ombudsman Commission from investigating violation of the leadership code. In Sir Michael’s case, it is his alleged failure to lodge complete financial returns for fifteen years beginning in 1992–93. On 13 December, time finally ran out for Somare to obtain an injunction to stop the public prosecutor from setting up a tribunal to hear charges of misconduct in office. He immediately said he was standing aside as prime minister and would take the opportunity to “clear his name.” He also claimed to be a victim of “gross injustice” because he had been unable to get his final appeal before a judge. The newly appointed deputy prime minister, Sam Abal, member for Wabag in the Highlands Province of Enga, became prime minister. Somare had stood down before the leadership tribunal was formed and began its investigation. It soon became clear that it would be several weeks before that happened. At that point it would be necessary for Somare to relinquish office. That gap between the voluntary and compulsory standing down would become important as events unfolded.

Abal, the foreign minister, had suddenly been appointed deputy prime minister a few days before Sir Michael stood down. A group of senior ministers and officials had flown to East New Britain on 7 December where they met the governor-general, Sir Paulias Matane, who reportedly signed the documents appointing Abal as deputy PM and making other changes to the ministry. On the following day, Don Polye, the previous deputy PM, said that he had received no news that he had been replaced. It was another day before the rushed changes were confirmed. Abal’s appointment was seen as a move by Somare to make sure he had a reliable and non-threatening replacement should he have to stand aside to face the charges of misconduct.

The man replaced

Polye was openly ambitious. In July 2010 when the then deputy prime minister, Puka Temu, resigned and joined the opposition to support a motion of no-confidence in the Somare government, Polye had appeared to equivocate. Temu hoped that he would join him in opposition, but Polye stayed with the government and was rewarded with Temu’s old job. Polye referred to the “Somare–Polye” government and announced that he would be a candidate for the prime ministership when Somare retired. This was seen as unwise self-promotion.

Polye is the member for Kandep in Enga Province, and there is much publicly available information about his election. He had a commanding win at the general election in 2007, but a court presided over by Judge Greg Lay considered whether “illegal practices” or errors by those conducting the poll had affected the outcome. In his long report Lay referred to some “very good liars in the witness box” and decided there was clear evidence of “ballot stuffing.” At thirteen polling places, Polye had received a credulity-testing 100 per cent of the votes. There were no damaged or informal votes.

Lay was sceptical about the voting at all thirteen booths and he found evidence that at some no election had been held. Two or three men had filled in all the ballot papers and another had folded them and “stuffed” them in the ballot box. At other polling places the electors were present, and they filed past or had their names called as a polling official filled out the ballot paper without consulting the voters. When a brave voter objected at one poll, a fight broke out; all voters were chased from the area and the officials continued to fill in the ballot papers.

Lay also heard evidence of fights breaking out and all ballot papers being destroyed at three polling places, of many places where scrutineers stood where they could see or hear voters make their preferences and so influence or intimidate them, and of the many illiterate voters being at the mercy of polling officials who filled in their ballot papers. Concerned with voting day itself, Lay did not consider the violence that had taken place during campaigning. He decided that over 7000 votes had been affected – greater than Polye’s winning margin of 6047 – and that the election was “absolutely void.”

During the campaign for the consequent Kandep by-election, held in November 2009, there were more reports of violence. At a rally addressed by Polye a tear gas canister was thrown into the dense crowd causing people to flee in all directions, and high-powered rifles, shot guns and bush knives were used in some clashes. The Post-Courier’s summary was that Kandep was “tense after a couple of deaths, serious injuries and destruction of properties worth hundreds of thousands of kina.” Polye had bullet holes in his new campaign vehicle, a result, he claimed, of police fire. But with the deployment of extensive teams of police and defence force personnel, the election itself was generally peaceful. At only three places was polling abandoned because of violence. The electoral commissioner ordered officials to return and conduct new polls where the disruptions had taken place, but the officials flatly refused. One told the National that “people were shot dead, there were road blocks and fighting with high-powered rifles right in front of our eyes.”

Because of the strong chance of intimidation and violence, the vote count was shifted to Hagen and then further east to Goroka. The officials attempting to take the uncounted votes from Kandep were confronted by logs across the road and armed men who “outnumbered and outgunned” the police until reinforcements arrived, the National reported. When the votes were eventually counted, Polye again won without the need to count preferences. He was readmitted to the ministry. Post-election violence and looting by supporters of winning and losing candidates continued in Kandep, according to the National.

A civil engineer by training, Polye is an able politician. He operates in a system in which police action is often inefficient or non-existent, clan violence recurs, guns are likely to be used in disputes and groups accept that corruption and intimidation will be used to secure advantage. Any candidate who had no group of tough supporters able to combat mobs waiting to break up election meetings, who promised to treat all citizens equally, and who offered no material rewards to influence voters would be in danger of losing his or her deposit. The Kandep electorate is not the worst and Polye is far from the worst of aspiring politicians. If he doesn’t become Somare’s successor then it may well be another MP who has survived a tough education in the politics of the Highlands.

By replacing Polye with Abal, another Engan, Somare avoided the anger of Highland politicians and their supporters, who would have resented the loss of a senior position. Immediately after he lost his position, opposition forces offered to nominate Polye as prime minister in a projected motion of no confidence in the government. He hesitated and then accepted the foreign affairs and immigration portfolio under Abal. But the change from Polye to Abal will have ramifications in Engan politics impossible for an outsider to predict, and it may also have an impact on the governing coalition. Many Engan, and more broadly Highlanders, have been supporters of Somare’s National Alliance. But as a Post-Courier commentator has written, “cranks and divisions [are] emerging in the ruling National Alliance Party.” The writer may have meant “cracks”; but let the reader allow both wit and insight.

Sam Abal’s appointment as acting prime minister immediately became enmeshed in the question of the appointment of a Governor-General. It was a problem and farce set in motion in mid 2010.

Appointing a governor-general

In June 2010 Sir Paulias Matane, an avuncular, long-term senior public servant, a one-time ambassador and prolific author of autobiography and admonitions to do good, completed his six-year term as governor-general. Papua New Guinea is not a nation where citizens wait to be nominated by the government and have their names forwarded to Queen Elizabeth, who is still the country’s head of state. Aspiring candidates for the vice-regal position promote their claims and lobby members of parliament – for some aspirants they are fellow members of parliament. But in June the government decided that it wanted to nominate Sir Paulias for a second term. While no governor-general in thirty-five years of independence has served two terms, Papua New Guinea’s long and detailed constitution clearly allows a second term. At section 87(4) it says that a person can become eligible for appointment for a second term if parliament supports the candidate with a “two-thirds absolute majority vote.”

When parliament met on 25 June most members thought it was going to consider the government’s proposal to add Sir Paulias to three other formally proposed candidates and then vote on the nomination of the next governor-general. But when the speaker, Jeffery Nape, said that the parliament was to vote instead on the eligibility of Sir Paulias, Sir Michael Somare moved that parliament resolve that Sir Paulias be nominated for a second term. A “scene of chaos and confusion” developed as members demanded to know what they were voting on and claimed that the process was not in accord with the constitution. People in the public gallery joined in the “shouts and abuses”; points of order were ignored. Without the speaker clarifying the motion, the vote went ahead and resulted in 84–13 in favour. The vote reflected the then dominance of the Somare government in the parliament. The government decided that Sir Paulias had been nominated and his name went forward to the Queen and he was confirmed as governor-general.

Immediately the vote was taken, serious commentators and angry members of the public (who may have supported other candidates) pointed to faults in the process. The National made its position clear: the re-appointment was “contrary to the explicit directions provided by the Constitution.” It asked that parliament be recalled, go through the process again and get it right. The government was unmoved, but in July Luther Wenge, governor of Morobe Province, said it was better to refer the matter to the Supreme Court rather than “rubbishing each other in the media.” His provincial government, he said, would pay for the referral. Wenge, a law graduate of the University of Papua New Guinea and once a judge, had previously initiated the challenge to the constitutionality of the Australian Enhanced Cooperation Program. To the detriment of the Australian aid program, he had won that case.

On 10 December 2010 a five-man bench of the Supreme Court delivered its unanimous and unequivocal decision. At the time parliament made its decision, the court pointed out, Sir Paulias was not governor-general and had properly been replaced, temporarily, by the speaker, Jeffery Nape. But Nape had continued to preside over parliament, which, as acting governor-general, he should not have, particularly when the business before the parliament was the appointment of the next governor-general. The constitution explicitly states that an acting governor-general must not hold another office. The court made other telling points. The open vote in the parliament securing two-thirds of the vote could make Sir Paulias a candidate but not nominate him to be governor-general; the constitution, the court said, required a “secret exhaustive ballot.” The process had been wrong and the other candidates had been treated unjustly. The court ruled that Sir Paulias cease being governor-general and the parliament meet as soon as practical within forty days to make an appointment.

At first the government argued that it would be going back to the Supreme Court to claim the court was in error; the acting speaker, Francis Marus (replacing Nape), said it was not practical to recall the parliament within forty days; and, reported the Post-Courier, acting prime minister Abal “was of the strong view that the Supreme Court had encroached on the legislature’s boundary.” The government also had its own self-interested reason not to recall parliament. When it had adjourned parliament in November 2010, the next sitting date was set as 10 May 2011. The long recess was a standard tactic to avoid the opposition moving a motion of no-confidence in the government. In its response to the speaker’s arguments to delay a recall, the court was unimpressed, even scathing: the government case was “bewildering” and amounted to a “litany of excuses for inaction.” The government soon accepted that it had a wrong to correct and that parliament would meet within the forty days.

By mid December 2010 several strange sequences of political events had coincided. The Somare family was engaged in a complex dispute with Waranaka, the governor of East Sepik Province, over Michael Somare Jr’s alleged attempt to shoot him. Sir Michael Somare had stood down from the prime ministership because of the impending formation of a tribunal to hear charges of misconduct. The deputy prime minister, Don Polye, had been replaced by Sam Abal and within a few days Abal had become the acting prime minister. The Supreme Court had ruled that the appointment of the governor-general was contrary to the clear process set down in the constitution, and Sir Paulias had had to vacate the office, leaving it in temporary limbo.

The PNG constitution sets down who will take on the vice-regal role should the governor-general be unable to perform his or her duties. The speaker was the first choice; should he or she be unavailable then the chief justice takes the office. If the chief justice is unavailable then the Executive Council can nominate a minister to be appointed by the Queen. For reasons that are unclear, Speaker Nape had been replaced by Francis Marus; but he could not act as governor-general because the office can only be held by the “substantive holder” of the position of speaker or chief justice. Sir Salamo Injia, the chief justice, was said to be on leave or about to go on leave.

It was therefore some time before the public knew that the government had chosen one of its own, Michael Ogio, the higher education minister, as acting governor-general. Just who was exercising the powers of the governor-general from 10 December, when Sir Paulias stood down, until the government announced Ogio’s appointment from 20 December is unclear. The gap may be important because it covers the time at which Abal became acting prime minister. If Abal’s elevation required vice-regal affirmation, then who officiated is unknown to outsiders. At the same time as Ogio was named acting governor-general, the Post-Courier reported that Abal and other senior members of the government had flown to East New Britain, home of Sir Paulias, to assure him that when parliament met he would be proposed as governor-general.

After 20 December Papua New Guinea had an acting governor-general, acting prime minister and an acting speaker, and the chief justice was on leave. There was also an acting commissioner of police. (The sacking of Gari Baki and appointment of Tony Wagambie as acting commissioner has been seen as a political act and has left a divided police force.) There was more acting in Port Moresby than at the Princess Theatre.

Complying with the Supreme Court ruling, parliament met on 11 January. The government made it clear that it had only one item on the agenda and that was the nomination of a governor-general. Having set down that candidates for nomination had to sign and lodge their forms by 4 pm on 12 January, the speaker, Francis Marus, adjourned the parliament until 14 January. With Marus refusing to notice the opposition’s attempts to raise points of order, any chance of raising a motion of no-confidence disappeared. In any case, the government had the numbers for the adjournment and it was not clear who the opposition was going to name as its alternative prime minister.

About ten hopeful candidates for the governor-generalship (including several knights) began rushing around hoping to secure a proposer and the signatures of the fifteen members of parliament required to validate their candidacy. Their chances of finding supporters diminished sharply when government members met and decided to support acting governor-general Ogio; forty-seven members signed his nomination form. Sir Paulias was abandoned; it was later claimed that only two members, Sir Michael Somare and Leo Dion, a member from Sir Paulias’s home area, were prepared to put their names on his nomination form.

On 14 January parliament met to nominate their choice of governor-general to place before the Queen. Only one other candidate was included in the secret ballot and Ogio was declared the winner. Whether other candidates who failed to gain a place in the starting barrier will take legal action is uncertain. Parliament was quickly adjourned to 10 May; as in previous years it will struggle to sit for the required minimum sixty-three days.

Further twists in the tale

As is often the case in Papua New Guinea, unfolding events continued to unfold. Government officials flew off to Buckingham Palace to inform the Queen of parliament’s nomination. Ogio will follow, and the Queen is expected to dub him “Sir Michael,” but there are further steps to be taken before he can be governor-general. The clearly written Papua New Guinean constitution requires that “before entering upon the duties of his office” the governor-general has to take the oath of allegiance and make a declaration of loyalty before the chief justice and “in the presence of the Parliament.” Unfortunately for the government, it had already closed down parliament until 10 May. Either the government recalls parliament – presumably for another one-item sitting – or Ogio remains acting governor-general (or governor-general elect) for four months.

There is another twist. Ogio, a teacher before he entered parliament, is the member for North Bougainville. Leaders of North Bougainville commended the government for selecting “one of Bougainville’s very own sons” for high office. But in the 2000 settlement ending the protracted civil war and war of secession, Bougainville became an autonomous region with a high degree of independence from Papua New Guinea. The 2000 agreement also provided for a referendum allowing Bougainvilleans to vote for full independence ten to fifteen years after the formation of the Autonomous Bougainville Government, which occurred in 2005. The arithmetic means that Bougainvilleans could opt for complete independence towards the end of Ogio’s six-year term. As the constitution of Papua New Guinea requires its governor-general to be a citizen, complex issues of nationality and citizenship could arise. Should Bougainville become independent, other Bougainvilleans who have flourished in the private or public life of the wider Papua New Guinean state will also have to decide whether they want to return to the smaller world of Bougainville.

Even before Parliament met on 11 January, there were rumours that Sir Michael was going to resume the prime ministership. This seemed to be confirmed when Abal said that Sir Michael was “on holiday” and could return whenever he liked. In a statement on 17 January the prime minister’s office announced that Sir Michael had returned from holiday leave to take up his duties again. Questions were raised about why there had been the strong statements in December that Sir Michael was standing down to clear his name. His spokesperson, Bertha, pointed out that the tribunal to investigate the prime minister’s affairs had not been established and Sir Michael was under no obligation to stand down until it was. His standing down had been turned into a holiday. Papua New Guinea once again had a prime minister rather than an acting one.

Reporting on the neighbours

Each of the developments making up this series of events deserves closer analysis; here are three preliminary observations.

First, it is often pointed out that through over thirty-five years of independence Papua New Guinea has retained its democratic government. Elections are fought vigorously, there are no political prisoners, there is freedom of speech and assembly, and members and governments are changed by voters. Among the newly independent countries with no tradition of a central government, high rates of illiteracy, low incomes and strong local loyalties, this is a significant achievement. But there has been too little concern with how the elected government works. The parliament’s cavalier approach to the constitution – deciding on a near six-month adjournment, not meeting the required number of sitting days, and allowing the government and the speaker to shut down debate on topics unpalatable to the government – is not indicative of a healthy democracy. How parliament now works cannot be rationalised by claiming that this is a result of making a foreign-imposed institution conform to Melanesian ways. Currently, government policies are not subject to debate in the parliament and the government disregards conventions and – recently – the constitution.

Second, other institutions in Papua New Guinea monitor the parliament and call it to account. Port Moresby’s two daily papers, the Post-Courier and the National, recorded events and commented strongly on what were seen as errors and inconsistencies. They condemned the process of nominating the governor-general in June 2010 and said it was likely that it would be challenged in court. They pointed to the number of acting positions, provided informed speculation on the replacement of Polye with Abal, and questioned the changing explanation of Sir Michael’s absence from office. In its judgement on parliament’s nomination of Sir Paulias as governor-general, the Supreme Court was specific and forthright, and the judges were sharp and uninhibited in their later exchanges with the speaker, Francis Marus. There is vigour and openness in some of the countervailing forces to executive government.

Third, the mainstream Australian media coverage of events in Papua New Guinea was fragmentary and analytical pieces were rare and brief. (Hamish McDonald in last Saturday’s Sydney Morning Herald was one of the exceptions.) Given that…

• Papua and New Guinea were administered by Australia for over sixty years

• Australians fought the battles of a world war there, Australia was responsible for preparing Papua New Guinea for self-government and independence

• Australia provides Papua New Guinea with over $450 million a year in aid

• Papua New Guinea now has a population of over six million (close to that of the Australia into which I was born)

• Papua New Guinea is rich in resources needing an efficient government to ensure they are exploited efficiently and to the national advantage

• and Papua New Guinea is a close neighbour with a long land border with Indonesia and lies at the junction of Southeast Asia and Australasia/Oceania

… then the Australian public should be properly informed about what is going on north of Torres Strait.

The two correspondents in Port Moresby feeding the Australian media, Liam Fox of the ABC and Ilya Gridneff of AAP, were reporting these events, but what appeared in Australia were brief accounts far from the headline stories. Gridneff’s 250-word report on the lower part of page six of the Canberra Times on 18 January 2011 was relatively long. Australians dependent on the mainstream media would have missed some of the key events and had difficulty gaining any sense of the continuity and intersection of others. Much could be followed online, but that was only an option for a minority with a special interest in Papua New Guinea. As a result, most Australians who think of themselves as well-informed missed the “cranks and divisions” emerging in our northern neighbour. •