“Em inap nau...” (“That’s enough now...”)

— Lady Veronica Somare’s plea to her husband, the PNG prime minister, Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, before he left for a heart operation in Singapore. She went on to say in Tok Pisin, “Let the young do the work” (National, 14 June 2011).

BY THE END of January 2011 the politics of Papua New Guinea appeared to have reached an impasse. For health, age and legal reasons, and because he was unwilling to stand again in the coming 2012 general elections, Michael Somare, the dominant political figure since independence, seemed unlikely to continue long in office. But among the contenders to assume the prime ministership, none had commanding personal authority or stood in an undisputed line of succession. Replacing Sir Michael was only one problem for a nation on the edge of billions in resource development income and with courts and a media struggling to make sense of parliamentary and party manoeuvres.

Nine months later, the situation was no clearer. Sir Michael, hospitalised in Singapore, “was retired,” the acting prime minister was displaced, the constitution came under close scrutiny and – at what seemed like the eleventh hour – an unexpected figure returned to parliament in a wheelchair. As is often the case in Papua New Guinea (as I wrote in my previous report for Inside Story), unfolding events have continued to unfold.

ENDEMIC corruption and violence mean that Port Moresby is perceived to be one of the world’s least desirable cities. One survey ranks the PNG capital seventh out of the worst ten, just above Caracas and Mogadishu. But the absence of a prime minister and the ambitions of the contenders circling for support and opportunity have provoked no demonstrations. In London, mob looting and burning led to a political crisis and the deployment of 16,000 police on the streets. In Port Moresby, a prolonged and nation-changing political crisis has left the streets – notorious for opportunistic violence – indifferent. Whether that separation of mobs and national politics will remain is another unanswered question.

Among all the known corruption and violence, PNG still retains some institutions fundamental to a fair and democratic nation. The government funds them and appoints competent officers not intimidated by the powerful and not themselves tainted by rumours of corruption. The Ombudsman Commission is one such institution that has consistently fought to fulfil its role as monitor of the integrity of those holding high office. In late 2010 and early 2011 it seemed that the greatest immediate worries for Sir Michael’s son and fellow MP, Arthur Somare, resulted from actions the Commission had initiated.

Both Sir Michael and Arthur were said to have failed to lodge income returns; in Sir Michael’s case this violation of the leadership code went back to 1992–93. Sir Michael had delayed facing a leadership tribunal for misconduct in office by claiming bias among officials, deficiencies in the drafting of powers assumed by officers and the injustice of being prevented from getting his appeal before a judge. Having almost exhausted his legal options, he became the first prime minister to be held to account by a leadership tribunal. Before the courts made a decision on Sir Michael’s final appeal, the chief justice moved to have a tribunal hear the charges. The tribunal, appointed in February, was a trio of retired and distinguished empire judges: chairman Roger Gyles, formerly from the Federal Court of Australia, Sir Bruce Robertson (Court of Appeal and High Court of New Zealand), and Sir Robin Auld (lord chief justice of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales). They arrived in Port Moresby in March this year.

Within a fortnight, the tribunal had made its decision: Sir Michael was to be suspended from office for two weeks. Sir Robin Auld had made a harsher judgement: he ruled that Somare was guilty of “serious culpability” and should be dismissed from office, but agreed to accept the view of his fellow judges.

On 25 March the National newspaper pondered the ironies and the justice of the decision. Nearly forty-five years earlier, Sir Michael had chaired the constitutional planning committee whose provisions were now being used to call for his suspension. The National thought it reflected very well on the nation that the prime minister could be subject to the tribunal and found guilty without any unrest across the country. But it wondered if the penalty was adequate. It concluded that although Sir Michael had received a mere “slap on the wrist,” this was balanced by the fact that his previously “unblemished record” was now blemished.

More criticism of the prime minister came in early July, with the Supreme Court’s ruling on Sir Michael’s action against the Ombudsman Commission:

These proceedings... [have] been a total waste of the court’s time. Besides, we find that these proceedings are a culmination of a history of unnecessary, improper and inappropriate steps taken by Sir Michael through his lawyers without having any factual and or legal foundation and merit. Clearly all the steps Sir Michael has taken in these proceedings amount to an abuse of process… (Grand Chief Sir Michael Thomas Somare, Applicant, and Ombudsman Commission, Respondent, page 68)

Over the four months to early August much happened but few conclusions and little clarity emerged. At the end of March, Sir Michael left for Singapore on what was said to be one of his “regular medical checks,” according to the Post-Courier, and he was due back in a few days. Just what his status was while initially in Singapore was uncertain. He had “stepped aside” when referred to the leadership tribunal, but this was said to be a “blunder” that was not required by the constitution; he could simply have said he was on “holiday,” it was claimed. In what appeared to be an official statement, acting prime minister Sam Abal said, with casual brutality, that Sir Michael was going “under the knife” but assured his fellow citizens that it was “nothing serious” and expressed the hope that Sir Michael would be back within a week. He even added – with an unnecessary flourish – that Sir Michael was “well and jubilant.”

But already the assurances of routine procedures and a quick return to prime ministerial duties were looking to be wildly optimistic. The first reports to reach a wide public that Sir Michael was seriously ill and faced dangerous medical procedures came on the weekend of 9–10 April when Catholic congregations around the country were asked to pray for their fellow believer. On 20 April, Abal conceded that Sir Michael would “remain on medical leave until further notice.” Over four months in early 2011 Sir Michael’s status at any one time may have been “suspended from office,” “voluntarily stood aside,” “on holidays” or “on medical leave.”

Abal and the Somare family continued to send out reassurances: Sir Michael was “recovering” and, in spite of being seventy-five and having more “corrective surgery,” he was not standing down as leader of the National Alliance party and it was “premature” to talk about electing a new prime minister. As for the rumours that he had died, they were “false, irresponsible, distasteful and disrespectful.” But the public – or at least that part of the “public” the media claimed to represent – was beginning to resent the lack of detail about the health of Sir Michael, who was in intensive care in Singapore. In a commentary piece on 31 May, the Post-Courier claimed that Papua New Guineans were “watching” and “they do not like to be treated with contempt.” The paper went on to point out that Somare had now been in hospital for eight weeks and there were still more rumours than facts. It was obvious that the government had not expected the severity of the illness or the long incapacity of their prime minister. But they should have: Somare’s precarious health had been “an open secret”; long before he went to Singapore he had dozed off in cabinet meetings, had difficulty breathing when climbing stairs and had “sweated a lot.”

Ambitious men who coveted the prime ministership were constrained. Some (including Abal) held their positions because of Somare, and if Somare went they went; some (perhaps all) were uncertain that there was a vacancy in the prime ministership; and Somare still carried such prestige that no one wanted to be among the first to say that Somare no longer had the capacity to lead the nation and that “I am the man to take over.” Potential candidates avoided criticising Somare by claiming that they were in his line of succession.

If there was any doubt of Sir Michael’s incapacity to intervene from afar it was dispelled at a media conference on 23 June, when Arthur Somare said he wanted to “talk about my old man’s health.” There was, he conceded, “great uncertainty” about Sir Michael’s recovery. Arthur said there would be no visitors other than family members – Sir Michael’s wife, Lady Veronica, and his children Betha, Dulcie, Sana, Arthur and Michael – who had maintained a vigil. Lady Veronica, Arthur said, had been fixed at her husband’s bedside and “might as well be part of the Raffles Hospital furniture.”

Until early June, the acting prime minister, Sam Abal, was behaving as expected: sitting in Somare’s leadership position but not making “any major decisions to move the country forward,” according to a Post-Courier report on 2 June. He was seen as “the ‘chief’s boy,’ a ‘political softie’... who will not ruffle feathers,” commented the National on 8 June. But on 4 June he suddenly controverted that assessment of him among allies and opponents by sacking Don Polye and William Duma from his ministry. Both ministers were thought to be favoured by Somare, both held key positions in the parties keeping Somare, then Abal, in office – Polye in the National Alliance Party and Duma in the United Resources Party. In dismissing Polye, who represents Enga Province, Abal also angered many of his fellow highlanders. Abal and Polye were now in dispute over control of the National Alliance Party and positions in the ministry; both disputes could add to the political cases awaiting resolution in the courts.

THE National of Wednesday 29 June began an article with an unaccustomed prelude:

Yesterday dawned an ordinary sunny Port Moresby kind of day – a little on the windy side – but before it ended, Tuesday, June 28, was propelled into the annals of PNG history.Shortly after 3 pm, an announcement was made that Prime Minister Grand Chief Sir Michael Thomas Somare was retired after nearly 50 years in PNG politics.

“Was retired, not “had retired”!

Arthur said that the family had made the decision three weeks earlier when Michael was in intensive care. He was in no state to make his wishes known, and the family had delayed any public announcement in the hope that he might recover sufficiently to be consulted. That had not happened. The National praised the Somare family for acting in the interests of the nation and of Sir Michael: these decisions truly make them “our first family.”

At last the citizens had been given what seemed to be an authoritative statement on the severity of the illness of their prime minister. They were being told he was unlikely to resume office or even participate at any level of national or East Sepik politics. It had been a long three months’ wait. The severity of Sir Michael’s incapacity was confirmed by Arthur who claimed he “had not talked to [his] father in weeks.” The public also learnt a little of the specific medical procedures Somare had undergone. His “personal physician,” Professor Sir Isi Kevau, reported that Sir Michael had developed complications after a second heart operation, forcing a third operation. In spite of the evidence, Professor Isi allowed the possibility of gradual recovery.

In Tok Pisin Arthur explained why the family had tried to open a path for the nation to escape the conflicting constitutional interpretations and personal ambitions: “Taim femili ino toktok, banis istap yet. Nau mi totok, mi kliarim rot. Em samting bilong palamen, kebinet na pati long mekim disisen. Em bai ino mo sanap long rot.” The National gave the following translation: “When the family did not speak out, it became an obstacle, but now that I make that announcement, it clears the road for parliament, cabinet and party to make a decision.”

As grand and unprecedented as the family’s gesture may have been, it was obviously of doubtful legality. Arthur’s claim to be “removing our father” from office had several effects on the leadership impasse.

First, it provoked lawyers in private practice, official positions and parliament to find out what the constitution – or an (unlikely) precedent from elsewhere – allowed in a situation where the nation had an ill and aged prime minister, hospitalised for two months in another nation and no longer capable of indicating whether he wanted to continue in office. The constitution provided no quick solution but its framers had anticipated the situation. Under section 142(5), the ways a prime minister “shall be dismissed” are listed; at (c) comes the necessary procedure. If the national authority responsible for licensing medical practitioners has reported to the speaker that two practitioners have jointly determined the prime minister is no longer either physically or mentally able to carry out his duties, he can be removed from office. Section 143 added that where the prime minister was “out of speedy and effective communication” the acting prime minister could exercise all the powers of a prime minister.

Second, under that reading of the constitution the office of acting prime minister (then held by Abal) had increased in importance, and its elevation might have opened another way to claim the substantive position of prime minister.

Third, Sir Michael was retiring (“being retired”) from several positions: the prime ministership, as member for the regional electorate of East Sepik (the electors had known no other representative since 1968) and as parliamentary leader of the National Alliance Party.

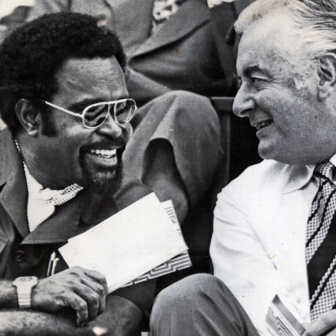

Fourth, it now seemed appropriate to pass judgement on Sir Michael: the man who had been the elected head of self-governing PNG in 1973 and independent PNG in 1975, a position he retained until 1980. He subsequently served two more terms as prime minister, the last, beginning in 2002, being easily the longest any Papua New Guinean had held the position. The premature obituaries properly praised his longevity and his steering of the nation through its first years and regretted that the “Great Unifier” would not be available to again lead the nation through a crisis. Muted criticism pointed to his failure to groom a successor; and the generous praise was on intangibles, not on what was practical and measurable: more and better roads, increased school attendances, more extensive health services, improved law and order, and job creation.

By the end of August, criticism of the failures of the Somare government were growing, but at first they were largely deflected by the charges of negligence and corruption being directed at ministers taking advantage of Somare’s incapacity. Specific and strong attacks were also made on Arthur, with less attempt to distinguish between father and son. At a meeting in the capital of the Southern Highlands Province, Mendi, “All speakers spoke generally of the concentration of power in the hands of a few, namely Sir Michael, his son Arthur and a few ministers who were also accused of failing to stay the advance of corruption in high places.” According to the National, Jamie Maxtone-Graham, the health minister, said: “Decisions were dictated and bulldozed down our throats. Arthur Somare used the position of his father to dictate to us. There was too much concentration of power in one family.” Sir Michael was no longer exempt.

Fifth, in the search through the constitution’s legitimate ways to replace a prime minister, another possible way – this time within the control of parliament – had been discovered. Under section 142(2) a prime minister was to be appointed after a general election or from “time to time” by the head of state (represented by the governor-general) acting on the decision of parliament. One of those occasions that might arise from “time to time” was when the prime minister was “absent from the country” or out of “speedy and effective communication” or “otherwise unable… to perform” his duties. Section 142(4) strengthened the powers of parliament and its officers to fill a vacancy. If parliament was not in session when a prime minister was to be appointed then the speaker was to immediately call a meeting of parliament with the appointment of a prime minister “the first matter for consideration.”

As a result, the lobbying intensified among members who thought they might be nominated for the fast track provided by the constitution. The Post-Courier of 20 June listed seven who were vying for support among their fellow members of parliament. When a candidate and his supporters thought they had built a majority in the parliament, they followed the tactics of others who had aimed to bring off a “political coup”: they gathered and isolated their supporters on an island or at a tourist resort to prevent their being seduced by greater counter-offers of positions and cash. On the eve of parliament resuming, they prepared for a dash through its procedures.

On 1 August the main opposition contenders, and many MPs from the government side who had now joined the opposition, gathered at former prime minister Sir Mekere Morauta’s well-positioned house on Port Moresby’s Touaguba Hill. A journalist who approached the house noticed about one hundred parked cars outside. The main aspirants at the “haggling table” were thought to be Don Polye, William Duma, Francis Awasa, Sir Mekere Morauta, Belden Namah and Peter O’Neill. The AAP correspondent in Port Moresby, Eoin Blackwell, said that Morauta and Polye were “instrumental in orchestrating” the leadership vote due the next day in parliament.

Parliament met the next afternoon. There was some confusion among members as they looked for seats following the various defections. The speaker, Jeffrey Nape, accepted the nomination of Peter O’Neill for prime minister by MP Belden Namah, seconded by William Duma, declined to hear all points of order or calls for divisions on the voices, and ruled that the nomination of O’Neill be forwarded to the governor-general, Sir Michael Ogio. Polye appeared “stunned” at the few members supporting him, according to the Post-Courier. The swearing in was completed by about 4.30 pm. Parliament reassembled later that afternoon (National, 3 August 11). The vote, seventy to twenty-four, was overwhelmingly in O’Neill’s favour. To secure such crushing numbers, O’Neill had split the votes of the major parties previously supporting Sir Michael – the National Alliance Party, United Resources Party, Pangu Pati and People’s Action Party. Only the party led by O’Neill, the People’s National Congress, moved as a bloc to the new government. The fracturing of the parties may be as important as the end of the nine-year Somare regime in allowing a reshaping and new fluidity in PNG politics.

Abal was unhappy. “I may not be a lawyer,” he said in a written statement, “but there is no procedure for the speaker to commence parliament and just presume vacancy of the position of prime minister when there is no legal documentation or substantiation of that move. The speaker hijacked the process and committed an illegal act.”

When releasing the names of those to hold ministries in his new government, O’Neill spoke of them as “simple and humble leaders for the people of Papua New Guinea.” He said that he had consulted political parties and leaders and “tried his best to cover all provinces in his cabinet.” It was a conciliatory statement that might be expected of a new prime minister. But, examined closely, it is clear that the distribution of ministries represented a sharp shift in power in personnel, parties and geography. The divided National Alliance had obviously lost its pre-eminence. Under Somare the East Sepik and West New Britain Provinces had been centres of power; now they were the only two provinces to have no representatives in cabinet. And there had been a marked change in representation from the north to the south. The highlands had secured the main economic portfolios: prime minister, finance and treasury, and petroleum and energy.

Peter O’Neill is himself the representative of a Southern Highlands electorate, Ialibu-Pangia, towards the east of the province. On the headwaters of the rivers flowing into the Purari, which makes its way to the Papuan Gulf, the electorate can claim to be both Papuan and highland. O’Neill, the son of an Australian father and a highlands mother, looks like a strongly built highlander. Fluent in English and with an accounting degree, O’Neill previously gained a reputation as an energetic and effective minister when he was in charge of several state-owned enterprises. His reputation was tainted by claims that he had fraudulently benefited from National Provident Fund transactions and, by creating the District Authorities, effectively given local MPs control over policies and funds, opening the way for them to “buy” greater influence.

One attempt by the Papua New Guinean government to reduce the frequency of court intervention and bring greater stability to the political system has been to introduce more controlling legislation: for example, the Organic Law on the Integrity of Political Parties and Candidates (OLIPPAC) 2001. The legislation encouraged parties to register, provided government funding for parties, committed party members to vote as the party decided on votes on key issues - no-confidence, the budget and the constitution. The new rules may have increased the role of the courts as they play a part in the interpretation of party constitutions that are now of increased complexity; the Organic Laws themselves have been challenged; and clearly in the election of O’Neill, members of parties felt free to decide for themselves which side they supported. In addition, the rushed vote for O’Neill may have violated other requirements of the constitution, such as the need for a notice of motion and the restrictions on a vote of no-confidence close to the scheduled next general election.

Something like this now seems to be the state of play in the contests for the prime ministership of Papua New Guinea:

• Peter O’Neill is recognised as the prime minister by most people. He has a cabinet and ministers and he bases his claim on the fact that the prime ministership was vacant and he was elected by a majority in the parliament.

• Sam Abal says he was appointed acting prime minister by Sir Michael when as prime minister Sir Michael clearly had the power to nominate a deputy. That commission, Abal argues, has never been withdrawn.

• Sir Michael may never have resigned the prime ministership; if so, there was no vacancy to contest.

As of 1 September Sir Michael has been able to speak for himself. “I am ready, willing and able to complete my term as the only legally elected prime minister of Papua New Guinea,” he told the National in a blunt denial of the view that he is mentally and physically incapable of returning to the position. He returned to Port Moresby on 4 September and attended parliament on 6 September in a wheelchair.

THE RUMOURS about Sir Michael’s ill health and the disputes about his replacement may not have excited the many unemployed on the streets or in the squatter settlements on the edges of the towns, or disturbed the rhythm of the women carrying home in the evening their heavy bilums (string bags) full of sweet potatoes and wood scrounged for a cooking fire, a little heat and a lot of smoke to ward off the highlands’ chilly nights. But the political impasse also meant the neglect of national issues that needed attention. Nearly all the indicators of welfare (health and literacy, for example) were stable or in decline.

One characteristic of the many claims and counter claims about the failure of past governments to combat corruption and ensure government services reached distant communities was, initially at least, the absence of criticism of Sir Michael’s many years in office. Coup leaders need to justify their actions, and when Peter O’Neill has done this he has condemned the interim government of Abal. O’Neill has found a convenient target; but given the brief regime of Abal and the fact that the system he took over was long in place, the criticisms have been unfair. The tribunal of eminent judges may have blemished Sir Michael’s record, but the public, his colleagues and rivals have been reluctant to exploit that exposure of weakness in the Grand Chief.

Given the inescapable problems to confront any new government of Papua New Guinea, perhaps we should be trying to explain why there is such competition for the prime ministership rather than accepting that intense rivalry is to be expected.

Papua New Guinea has survived nearly nine months without its being clear who holds the prime ministership and without the benefit of a disciplined cabinet. Given the lack of violence, the possibility of long delays of cases enmeshed in the courts and the need for time for new political alliances to stabilise, it might be desirable for the process of gradually acknowledging the end of the Somare era to continue for a little while yet. The last thing that the peoples of Papua New Guinea and of neighbouring nations (Australia, Indonesia and the Solomons) want is a Papua New Guinea descending into violence.

But the wild, enthusiastic reception given to O’Neill on his first return to Mendi after his election as prime minister was not an indicator of a gentle acceptance of change. O’Neill and his fellow ministers were honoured with a combined police and correctional services guard and greeted with a massed audience on Mendi oval. The enthusiasm for O’Neill and his 70–24 vote in the parliament may make the courts reluctant to stand up to the two other dominant formal and informal political forces in the country, the parliament and the crowd.

The potency of sentiment (but not the violence of crowds) has already been demonstrated when O’Neill went to his home electorate and the crowd claimed that he should be elected unopposed in 2012, at the University of Papua New Guinea where he was strewn with flowers, and at the National and Supreme courts where two sides gathered in support of either O’Neill-Namah or Abal-Somare. With the unexpected twists in the story so far and the speed with which unpredictable crowds can gather, it is uncertain that Papua New Guinea will have the luxury of time to establish a government that has a chance to be stable and efficient. •

Sir Michael Somare failed to gain a National Court injunction to keep his seat in the PNG parliament on 20 September. AAP reports that “Sir Michael had been seeking an injunction against his dumping from his East Sepik seat earlier this month by Speaker Jeffery Nape, who said the former prime minister had missed three consecutive sittings of parliament - grounds for dismissal under PNG law.” His lawyer, Kerenga Kua, said Sir Michael would appeal against the ruling in the Supreme Court.

Hank Nelson is Emeritus Professor and Visiting Fellow in the School of Culture, History & Language at the Australian National University.

Ripples of distant and not-so-distant eventsChina and PNG’s resource boom: On the north coast of Papua New Guinea, near Madang, the Chinese are developing a billion-kina nickel and cobalt mine. They have already been in the courts arguing about the disposal of tailings at sea, the introduction of unskilled Chinese labourers and the use of traditionally owned lands for roads and slurry lines. On the south coast the much bigger EXXONMobil Liquefied Natural Gas project (closer to 20 billion kina, or A$8.7 billion) extends pipelines and roads into the highlands. With some licence it is possible to see Papua New Guinea as another point where Chinese and US influence meets, or will meet.

Asylum seekers: On 21 August the Australian high commissioner in Port Moresby signed a memorandum of understanding with Papua New Guinea’s foreign minister on the reopening of the Manus detention centre for asylum seekers. After it was known that the O’Neill cabinet favoured the reopening, but before the MOU had been signed, Powes Parkop, lawyer and Manus Islander, came out with a strong statement saying that the reopening of the centre was “illegal and unconstitutional” and that he was prepared to take his objections to court. The Manus case illustrates the difficulty Papua New Guinea has with keeping government decisions from being enmeshed in the courts and the government being able to speak with one voice.