THE dismissal of Pakistan’s prime minister, Yousaf Raza Gilani, by the Supreme Court on 19 June sent waves of uncertainty through Pakistan. It’s still far from clear what the decision will mean for next year’s national elections, and particularly for the ruling Pakistan People’s Party.

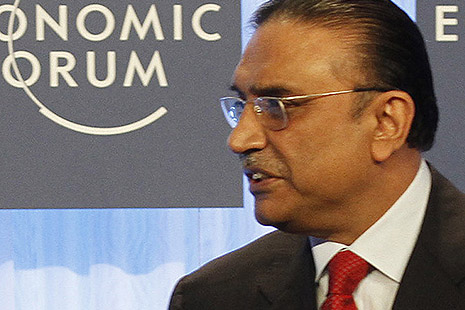

Already there are signs that the judiciary and the government will remain at loggerheads: the court arrested President Asif Ali Zardari’s first choice as new prime minister, Makhdoom Shahabuddin, on charges relating to the illegal production of a controlled drug. Zardari’s second choice, Raja Pervez Ashraf, was sworn in on 22 June and immediately attracted controversy. The former water and power minister faces allegations of corruption related to his tenure as minister.

These political upheavals add to the many uncertainties that plague Pakistan, from the insecurity of much of its territory to the faltering national economy. Combined, they distract the public and the government from chronic problems and provide an excuse for inaction. Some political figures also try to blame “foreign hands” for the country’s problems. According to Pakistan’s interior minister, Rehman Malik, foreign hands are behind the violence in Karachi, the civil unrest in Gilgit-Baltistan and the parlous state of Pakistan’s economy – and in these cases, Malik intimates, the United States, Israel and India are the foreign hands at work.

The Urdu and English language press have taken up this theme with baseless stories from conspiracy theorists, among the most extravagant of which are recent claims that the United States is using dengue fever as a weapon to kill Pakistanis and that Imran Khan is a Jewish agent.

Meanwhile, the government remains unwilling to focus on and take responsibility for Pakistan’s deteriorating economy and to implement the policies necessary to increase the country’s wealth. The country’s leaders seem incapable of frank self-analysis, preferring to blame others – other countries, other political parties, the military… the list goes on.

The energy sector – part of prime minister Ashraf’s previous portfolio – is in the grip of poor management that affects almost every part of the economy. The government’s latest solution to the sector’s malaise, reported in Pakistan’s English-language press in May, is simply to print more money to deal with its “circular debt” problem. It’s not that the idea of printing money to shore up government revenue and pay off debt is a new or necessarily bad idea. And, to be fair, this approach is not unique to Pakistan: governments in both emerging and established democracies have grappled with the difficulty of inflicting tough economic reform on their citizens. But by failing to deal with longer-term problems it highlights the expedient thinking of Pakistan’s government.

Taxation is a key example of this thinking. Guatemala, with its population of fourteen million people, has more registered taxpayers than Pakistan, where the population is approaching 200 million. Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio is 10 per cent, well below that of neighbouring India (17.7 per cent) and nearby Sri Lanka (15.3 per cent). Despite considerable badgering from international financial institutions and the donor community, the government has been reluctant to do anything about this problem. The International Monetary Fund’s most recent loan package to Pakistan required the government to broaden the tax base and introduce a value-added tax; Pakistan cancelled the loan before the final tranche was paid because it could not meet those conditions.

The budget numbers make it blindingly obvious that Pakistan needs to do more to increase revenue. In 2010–11, 30 per cent of Pakistan’s net revenue came from external resources or foreign grants and loans. As a result, Pakistan pays close to R698 billion (A$7.2 billion) each year in domestic and international loan servicing, almost double the amount that the government receives in aid and loans. And which programs suffer as these funds head offshore? Overwhelmingly, it is the provision of social services.

Yet tax cuts will be introduced ahead of the federal election in 2013. Finance minister Abdul Hafeez Shaikh has also announced that there will only be two taxes in the budget: income tax and sales tax – hardly a policy that will put Pakistan back in the black. Pakistan needs to look more broadly at its tax revenue potential and start imposing more wide-ranging taxes on land holdings and on agriculture, two sectors that are sorely undertaxed owing to the strong vested interests of Pakistan’s wealthy elite.

In 2010–11, Pakistan allocated R7.3 billion (A$76 million) to the health sector and R34.5 billion (A$357 million) to education. Only R3.2 billion (A$33 million) went to support primary and pre-primary education. As a percentage of GDP, spending on health and education in Pakistan is lower than in Sub-Saharan Africa. And the impact of this underfunding is clearly evident in Pakistan’s development indicators. Around 31 per cent of children under five are underweight and around half of the population is illiterate. On these two indicators Pakistanis are worse off than Angolans, Haitians and Congolese. Pakistan, Afghanistan and Nigeria are the only countries in the world that still report cases of polio, yet Pakistan has the sixth-largest army in the world and possesses nuclear weapons.

The main tax avoiders are the elite, who have made tax avoidance a national pastime. The politicians who make the rules are among the country’s richest citizens, and are adept at finding ways to exempt themselves from income and property tax. It has been reported that the national opposition leader, Nawaz Sharif, did not pay income tax between 2004 and 2007, despite the likelihood that his income as an industrialist is in the millions.

According to a former Federal Bureau of Revenue official, Pakistan has “a skewed system in which the poor man subsidises the rich man.” The implementation of a broader income tax system would have citizens demanding more of their government in exchange for their tax dollars, which in turn could strengthen democracy in Pakistan.

Not many people have good things to say about paying tax, but for Pakistan it could be the right medicine to improve its economy and to hold the government to higher standards of service provision. In a country trending downwards on development indicators, this could only be a good thing. •