They’re a Weird Mob

By Nino Culotta | Text Classics | $12.95

They’re a Weird Mob

Directed by Michael Powell | Roadshow Entertainment | $12.95

IT’S probably a bit shaming for someone who was around at the time, and more or less mature even then, not to have read They’re a Weird Mob when it first came out more than half a century ago. Like everyone else, I knew about it, of course, and its reference to “King’s Bloody Cross” quickly became iconic, encapsulating a place, a time and an experience.

The book, first published in November 1957, had gone through seventeen impressions by March 1959, according to the edition I’m at last reading. In fact, They’re a Weird Mob “was reprinted every year for the next thirty-eight years. It sold the best part of a million copies” and the movie derived from it in 1966 “echoed the novel’s success by breaking all box-office records for a local production,” according to Jacinta Tynan in the introduction to this new edition. In other words, Nino Culotta (the pen name of John O’Grady) gave birth to a publishing – and, indeed, a cultural – phenomenon back in the remote 1950s.

Coming to it now, decades later, I wondered how dated it would seem, and in what ways. Perhaps the first thing that struck me was the mildness of its swearing: in a time in which variants on the “f” word are common linguistic coinage it’s hard to remember when “bloody” or the occasional “bugger” were the characteristic epithets for expressing outrage. On the matter of language, O’Grady exercises remarkable tonal control over the sloppiness of everyday diction: the endemic use of “ut” instead of “it” (as in “Nothin’ to ut, mate”), for instance, or the slurring together of several words into a semi-literate version of those long German words made by the simple adding of shorter ones to each other (as in “’Owyergoin?”). But it’s not just the language that seems so innocent, so devoid of concern for possible offence; it’s the way Culotta renders the unthinking response to, say, “New Australians” or “sheilas.” It seems less a conscious attempt on the part of the working men to diminish those they’re referring to than a total imaginative failure to grasp any sense of otherness. “Innocent” is hardly the word for it, but neither is “vicious.”

What interests me now is the balance O’Grady maintains between critiquing and celebrating the Australia into which he plunges his narrator. Nino is a north Italian journalist whose editor has sent him on a fact-finding mission to postwar Australia, which has become a goal for Italian migrants. Language is, of course, central to his coming to terms with the experience, and his growing rapport with the builder’s labourers derives in part from his gradual grasp of such essentials as the idea of “shouting” in a pub – both the word and the idiotic practice of being in a drinking school that requires him to have more “schooners” than he wants or needs. It was a clever notion of O’Grady’s to make Nino a journalist because this provides a legitimate narrative device for some reflections on what he is making of his time Down Under (as it was no doubt thought of). For instance:

I wish I could reproduce the accent, and the close-lipped rapid enunciation. I have thought of using a tape recorder to capture it. But when an Australian is asked to speak for a specific purpose, everything that makes his conversations the delight they are, disappears.

This kind of rumination gives the book a lightly worn seriousness that punctuates but doesn’t puncture the sheer good-natured fun of so much of it. The differences in sense of humour – perhaps crucial to any country’s sense of itself – also emerge early among the ways in which Nino will come to understand his new country. “Getting” a joke in a foreign language may well be the best sign of assimilation.

The element of critique, albeit lightly worn, is there in attitudes to xenophobia and racism. There are jokes about “niggers” (in a comment about Gone with the Wind), about “Ities” and/or “bloody Dagoes.” (“Who won the war? We did, didn’ we?” one charmer asks rhetorically as he puts down the postwar influx of Italians.) But O’Grady doesn’t fall into the trap of crudely attributing such qualities only to ignorant, insular Australians. He avoids this by having Nino record his prejudice against the Meridionali: “These are Italians from the south of Italy. They are small dark people with black hair and what we considered to be bad habits. We are big fair people with blue eyes and good habits.” He recalls how he had “drunk a lot of vino, and kept on yelling out ‘dirty Meridionali’ and other things” just before boarding the ship to Australia. O’Grady captures accurately the unthinking attitudes of the complacent era he was writing in and makes clear that, however insular we were, we didn’t have a monopoly on such prejudices.

Nino’s manners appear courtly by comparison with those of the rough-and-ready Australian blokes who are his workmates, and there are a couple of interesting points made by this contrast. First, as with almost everything about his adjustment, Nino’s formality is a by-product of linguistic uncertainty in his new environment. Second, when the workmates parody his diction and manners, it makes one wonder if the slapdash ockerism of their everyday speech isn’t a conscious assumption of an anti-British vernacular. When foreman Joe’s wife, Edie, serving breakfast, wonders aloud “why he couldn’t learn to speak nicely like Nino,” other workmates, Dennis and Pat “began to imitate my speech in an exaggerated manner”:

“I say, old chap, would you mind passing me another slice of that excellent toast?”“Not at all, old man, I always think toast refreshes one, do not you?”

“Indubitably. Indubitably. But I must say the coffee is superb.”

“Superb, my dear fellow, is an understatement. It is elegant. Only the sublime technique of our kindly host could produce such a delectable beverage.”

And so it goes on. “Stretching credulity” was my first reaction to this, but then it seemed more interesting to wonder if the author wasn’t slyly making a point about the everyday locutions of Australian blokes desperate not to be caught seeming old-world or affected in any way. Perhaps their diction was just as much “put on” as that of the Poms – or, indeed, of any more mannerly types – they are mocking.

O’Grady parades such Aussie rituals as pub-drinking, rabbit-shooting and the local procedures for courtship and marriage. And these are offered with both affection and satirical observation. Nino himself, adjusting seriously to the contemporary mores, decides “I am going to get married” and applies himself to this project with the same earnestness as he does to acquiring the idiom of his fellows. This decision leads him to The Corso at Manly beach, where he makes the acquaintance of two young women, one of whom, Dixie, is waiting for her fiancé, Charlie, and is trying to eat spaghetti with a spoon. She is not responsive to Nino’s advice to use a fork. Her friend Kay replies to Nino’s telling them, “I am looking for someone who is my type, and whom I can marry,” with the terse rejoinder, “Have you tried the zoo?” In time he will overcome Kay’s lack of interest, woo her mother’s approval with a bunch of flowers and overcome her father’s resistance (“First bloke that’s stood up to me in years,” he tells his daughter approvingly). And in time again, he will have cleared the hurdle of being “a bloody New Australian,” one of those “who are still mentally living in their homelands,” and will thank God “for letting me be an Australian.”

The book ends on a paean of praise to Australia and its egalitarian ways. This can be read as Nino’s journalistic summarising of his views, and this function of his profession needs to be kept in mind so that the ending doesn’t seem merely to bathe everything in a warm glow. Nino has worked with Australians, lived among them, observed them with a receptive mind and an appraising eye, and married one of them. Even so, his impressions are offered without sentimentality. We don’t feel we’re headed for a group hug; instead, we are left with a work of charm and good humour that allows a certain degree of critique along with a modicum of satisfaction with the way we are.

Or, in 2012, the way we were. Apart from the book’s intrinsic values as a piece of imaginative writing – for instance, its tonal control as it moves between situations dramatised in dialogue and journalistic commentary, between Nino’s careful diction and the cheerful slipshoddiness of his mates’ vernacular – it has acquired almost an historical dimension. In its pages are preserved with verve and shrewd humour all sorts of cultural information about an era that now seems impossibly remote in many ways. It predates the admirable emergence of the idea of multiculturalism that I now associate with the likes of Al Grassby, the vividly suited immigration minister in the Whitlam government. It recalls both the greater innocence preceding the psychedelic explosion of the 1960s and the easy intolerance of so much of our thinking about “others,” and it does both with energy and grace.

WHAT, I wondered, could have attracted the British director Michael Powell to adapting They’re a Weird Mob for the screen? At the time, actor-producer John McCallum was the managing director of J.C. Williamson’s theatre chain and was keen to see the company embark on film-making again after a long interval. McCallum arranged the deal between “the firm” and Powell to make the film for $600,000, and the result was a big commercial success in Australia but not elsewhere. Powell needed a hit after the disaster of Peeping Tom (1960), now regarded as a masterpiece but then almost universally reviled. It finished Powell’s illustrious maverick career in Britain.

Apart from the prosaic reality of Powell’s need to kickstart his career, the film does reveal a certain continuity with some of his more prestigious work. The element of cultural difference, treated for comedy in Weird Mob, had claimed Powell’s fascinated attention in such diverse works as The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Canterbury Tale (1944), I Know Where I’m Going! (1945), A Matter of Life and Death (1946) and Black Narcissus (1947). There are touches of comedy in how, say, the American sergeant reacts to English habits in A Canterbury Tale, though for the most part in these films the matter of cultural difference is embedded in more serious entertainments. The Anglo-American rapprochement of A Canterbury Tale and A Matter of Life and Death was a serious business in the mid forties, but the first of those films and the Anglo-German amity depicted in Colonel Blimp can be seen as studies in friendships and understanding which override differences in language and nationality, while I Know Where I’m Going! and Black Narcissus offer explorations of women coming to terms with strange physical and/or social environments. I’m not mounting an auteurist case for Weird Mob as belonging in the director’s canonical achievements; I simply want to suggest that it might be less of a departure, in thematic interests at least, than might have been supposed. The celebration of Australianness is not so far removed, at core, from the magisterial eulogy to Englishness that concludes A Canterbury Tale.

In terms of technique, Weird Mob doesn’t do much to recall the visual splendours of Powell’s greatness in the forties but there are touches that suggest he is using the beauties of Sydney for something more than just postcard pictorialism. Stretches of Bondi beach seem to stand for Nino’s natural, unaffected delight in the country’s possibilities, and contrast with the building site he works on or with the conventional interiors of pubs or houses which create other contexts for the life he is coming to terms with. There is also a moment of focus-distortion to render Nino’s exhaustion that recalls some of the evocative power and precision of Powell’s genius, but it would be wrong to make great claims for the film, which is essentially an easy-to-enjoy entertainment put together by a director who could almost have made it in his sleep.

As an adaptation, the film retains the novel’s characteristic procedure as a series of more or less discrete episodes – Nino arriving, Nino at the building site, Nino in the pub – but in one major matter it strikes out and acquires a more obvious “shaping” than is found in the book’s narrative procedures. This is to do with the enlargement of the role of Kay, whom Nino marries. Whereas she doesn’t appear in the novel until over three-quarters of the way through, the film introduces her in a very early scene at her workplace and we have a sense of her background when she pops up in a not-too-likely coincidence on Bondi beach. When Nino announces “I think I’m going to get married” we have been prepared for it in a way that costs the film some of the novel’s comedy.

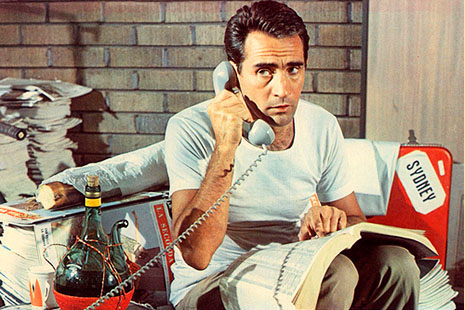

But the scene in which Nino meets Kay’s father, played by Chips Rafferty in a role that epitomises his brand of authoritative self-made Australianness, builds very satisfactorily both as a comedy confrontation and as a climax to Nino’s absorption, without loss of self, into Australian life. One might add that if Rafferty was by then regarded as an Australian “icon” (that word again), the same might have been said of Walter Chiari, who played Nino, in relation to his native Italy. He’d become internationally famous for co-starring with Ava Gardner, on and off the set of The Little Hut (1957), as well as for dozens of Italian films. The film thus ends on a note of mutual acceptance by two matched charismas.

It’s good that we no longer talk about “New Australians,” let alone “dagoes,” and we’d hope there has been serious progress in the ways that Australian men treat and talk about women. If it didn’t sound too solemn, I’d say that O’Grady’s book now has historical significance – as well as offering a nostalgic wallow for those simpler times. •