Einstein on the Road

by Josef Eisinger | Prometheus Books | $38.95

AN ABIDING irritation for Australian scientists is the fact that, unlike for sports personalities or film and television stars, their achievements go largely unheralded. It’s not that they aspire to become celebrities, rather that with recognition comes support for their work.

There’s a further annoyance. When scientists are noticed, they are stereotyped as lab-coat-wearing geeks. Who knows why the media thinks it is “quirky” that a polymer chemist is a rabid Essendon supporter, or a medical researcher plays bass guitar in a heavy metal group – but it drives career scientists to distraction.

So there’s a certain irony in the fact that for much of the twentieth century, one of the most recognisable faces, the ultimate photo opportunity, the person whom everyone wanted to meet, the Nelson Mandela of his time, was a scientist, Albert Einstein. What’s more, Einstein’s public persona as the gentle, otherworldly eccentric with the hair going everywhere – the man who wore no socks – is more than a little responsible for the scientist stereotype.

Looking back eighty or ninety years, it’s hard to grasp the scale of Einstein’s celebrity between the two world wars. People turned out in their tens and hundreds of thousands just to see him and hear him speak – even though, as with Stephen Hawking, most didn’t understand a word of it. For all that, Einstein was an intensely private person for whom the unbidden “celebrity” status was hugely irritation, even painful.

The great achievement of Josef Eisinger’s Einstein on the Road is to get beneath that public surface and discover Einstein the man, writing in his travel diaries. Apart from his letters, these diaries appear to be the only truly candid thoughts to which we have access. And the picture they paint is of someone of enormous intellect and humanity in all senses of the word – a person who was immensely warm and generous, but not beyond criticising his colleagues or his fellow Jews; who at times was prescient, but not always right or even consistent in his views, and had prejudices; but who took delight in music-making, the interplay of light and cloud, and the constancy of his friends.

The price the reader pays for this unprecedented intimacy is having to plough through what is, at times, a somewhat repetitive travelogue, and to wrestle with a poorly edited set of notes which are pivotal to the context and understanding of the book – especially for the vast majority of people whose knowledge of 1920s and 30s European history and science is sketchy.

The author, Josef Eisinger, is a physicist who escaped from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1939 and has lived in North America ever since. Still a student, he was interned in Maritime Canada at the beginning of the war. Later, he was released under the sponsorship of the Mendel family, who lived in Toronto. They were close friends of Einstein and, not surprisingly, Eisinger developed an interest in the man both professionally and personally.

Because of this association, he was contacted a few years ago by an Einstein researcher, who subsequently introduced him to the Albert Einstein archive at Princeton University, where Einstein spent his last twenty years. There, Eisinger found the travel diaries, which had never been published.

Einstein kept a diary only when travelling. But between 1922 and 1933, when he was in his forties, he travelled a lot. These diaries were written for his own use, and provide an almost unparalleled look at his day-to-day thoughts.

They don’t, however, necessarily provide a balanced view of what he was thinking. Close to the end of the text is a discussion recorded by one of Einstein’s friends in Oxford. “The conversation turned to diaries, and Einstein remarked that he had kept a diary on his recent American tour, but the most interesting things he had experienced he had never written down” – a revelation that comes as something of a letdown for the reader.

During his time “on the road” – mostly at sea, in fact – Einstein visited Japan and China and places in between; Palestine and Spain; Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay; the United States and Central America, several times; and England, several times. As well as the opportunity this afforded to interact with foreign colleagues and visit important research institutions, Einstein clearly relished the seclusion of the sea voyages and the time they gave him to think and read. Perhaps more importantly, he was able to get away from Germany, particularly Berlin, where the turn of events in politics and society, and the associated rise of the Nazi party, were disturbing him more and more. In the end, his travels allowed him to set up a future for himself and his family in America.

The book follows each of his journeys. They are enclosed by an initial chapter and an epilogue, which set the scene and provide a dénouement. But there’s more. Before the scene is set, there are – count them – two separate forewords, a preface, acknowledgements, an introduction and a timeline; later, there’s a bibliography, an index and notes. This is a well-documented, though perhaps over-documented, volume.

The greater portion of the book is in the form of indirect reporting of the contents of the diaries, bolstered by explanatory material and supporting evidence from contemporary sources. In his introduction, Eisinger is at great pains to point out that everything he attributes to Einstein – feelings, observations and comments – is based directly on what is in the diaries. The book is at its best, however, when Einstein is quoted directly, expressing his annoyance at local bigwigs (Grosskopfeten) or organisers (Affen, apes or idiots), or his delight at the sunlight in the American desert. Perhaps the material was not available, but I would have appreciated more of these direct quotes; whenever they appear, they have great resonance.

Many themes recur through the book. Einstein’s vast love of music and his great skill as a violinist, for instance, are inescapable. He devotes an inordinate amount of energy to organising opportunities to play chamber music with whoever is available, wherever he is – on the high seas, or in China or Latin America. Clearly, music is an enormous resource, refuge and recreation for his mind. He devotes equal energy to the cause of pacifism, giving impromptu speeches and carefully programmed radio broadcasts.

Einstein’s greatest scientific achievements were the four papers he published in 1905 while he was still working as an examiner in the Swiss Patent Office in Bern, including one outlining his Special Theory of Relativity. He followed this up with his General Theory of Relativity in 1916. After that, although he contributed important observations and debate, his major contributions to physics were done. After 1905, his reputation was assured. But it was only in 1919, when the English physicist Arthur Eddington announced to the Royal Society in London that he had measured the deflection of starlight by the sun’s gravitational field – as predicted by the general theory – that Einstein achieved rock-star status.

In the decade when he was travelling, much of his time was taken up with chasing a unified field theory to underpin physics. This was the Holy Grail he never found. He was constantly devising new approaches, only to recognise, or having colleagues point out, their fallacies. It’s a fascinating commentary on the science of the time that no one thought any the less of him for getting things wrong. He was allowed to make mistakes.

We tend to think of our era as one drawn together by the power of the internet – that science has never been so global. But this book and Einstein’s travels show that the scientific world between the wars was also “small” and equally active. Einstein seems to have met or corresponded with most of the great figures of physics of his time – and many more interesting people besides. Despite his horror of public engagements, dinner suits and the endless shaking of hands, he relished intellectual debate and exchanges of views.

EINSTEIN also had his biases. He believed that the world, and the science that explained it, should have a beauty – an aesthetic appeal – about it. So despite contributing to its development, he wasn’t happy with the description of light in terms of both particles and waves. And while he predicted the necessity of quantum mechanics, he never warmed to the descriptions of fundamental matter in terms of probability that his colleagues Bohr, Heisenberg and Born provided. “God does not play dice with the world,” he famously declared.

Unlike for many, however, his prejudices and ideology never seemed to obstruct his vision. If the theory or the science wasn’t to his taste, he didn’t discount it, he simply looked for a better explanation based on evidence. And, in the case of his unified theory, he never found it. Maybe this provides a lesson to contemporary politicians for whom the current state of science on climate change and alpine grazing goes against the grain.

Eisinger is punctilious, almost to a fault, in providing the reader with helpful background information. Do we really need to know the tonnage, top speed, name changes and eventual fate of every vessel Einstein sailed in? There are, however, areas where more information would have been of interest. Here, one suspects, Eisinger’s own sensibilities may have intervened.

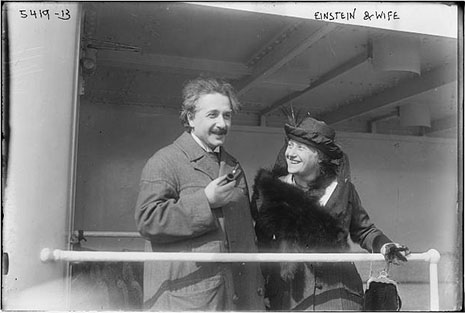

It is well known – and quite clear from the material in the diaries – that Einstein had an eye for the ladies. As Eisinger points out a couple of times, he was known not to set great store by monogamy – although he was devoted to his wife Elsa, who accompanied him on most of his trips. Beyond those few comments, though, nothing more is said. A little more information about this side of Einstein’s character, which undoubtedly manifested itself during his travels, would have been of interest, not for prurience so much as to judge the impact, if any, that it had on his life and work.

The worst aspect of the book are the nearly 250 explanatory endnotes in 170 pages of text. To use this information the reader must flip back and forth, once or twice a page, to the information at the back of the book. Because the numbers in the text are placed at the end of sentences, even if the reference is to information at the beginning or in the middle of the sentence, the notes often refer to unexpected aspects of the text. Not only are the notes repetitive, but in several cases the information they contain is provided elsewhere in the text. In one chapter the numbering is incorrect. Some of the information – for instance, the aforementioned shipping news – is hardly essential, and much of the rest could have happily been included in the text itself, without interrupting the reader. This loose editing is all the more surprising given that such care is taken with the overall documentation.

Fewer notes, at the expense of a little more information in the text, and placed at the bottom of the page – in short, a better job of editing – would have contributed to the ease of reading what for the most part is an unusual and interesting introduction to one of the towering characters of the twentieth century. •