The Abbott government’s problems began long before the 2014–15 budget, but now the budget is at the heart of them. It has failed to win support from the voters, and failed to win support from the Senate.

Why? I think there are two reasons. The first is that its measures, taken together, fail the test of fairness. That’s well known, and the opinion polls show the public’s reaction. The second is not well known, but it may have been grasped intuitively by many Australians, which is why the government’s appeals to national interest have fallen flat. In short, the sum of the government’s actions is not to reduce the budget deficit, but to rearrange it.

And now, as treasurer Joe Hockey will tell us on 16 December when he releases the heavily revised Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, or MYEFO, the plunge in mineral prices and the economy’s failure, yet again, to meet budget forecasts mean a return to surplus is now just a distant goal, and we will face big deficits all the way to the next election.

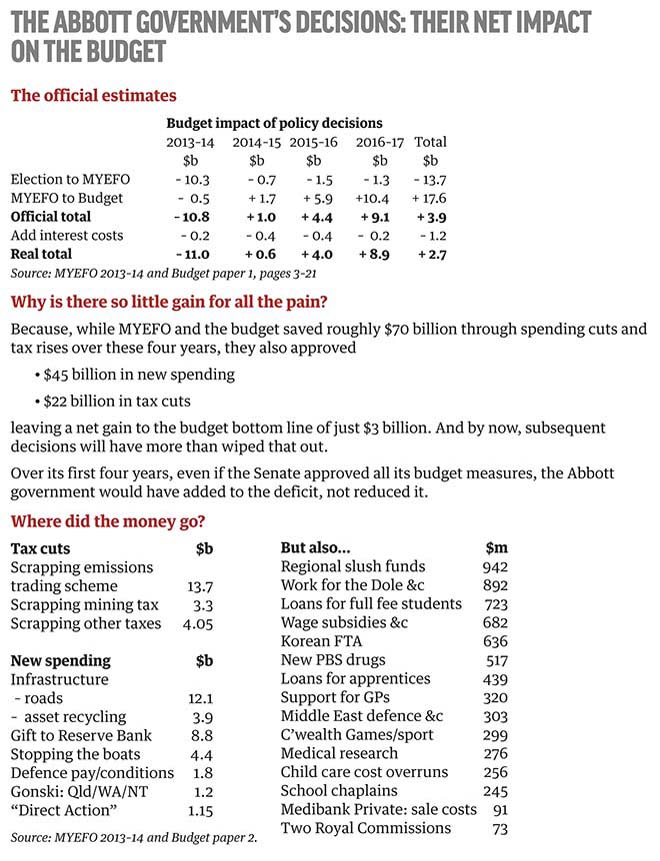

But even back in May, if you looked at the budget numbers, the net impact of the Abbott government’s policy decisions would have cut the deficit by just $4 billion over its first four years in office. Add in a crucial cost the budget numbers left out, add in the extra spending approved since the budget, and the net impact of the government’s decisions has been to increase the budget deficit – not to reduce it.

We’ll come back to that. The central issue in the public debate over the budget has been fairness. It is what has sustained the Senate’s opposition to the budget measures – even those that economists, including this one, would see as well-targeted.

Much of this ground was well covered in an earlier Inside Story essay by the Australian National University’s Peter Whiteford. I will simply plagiarise some of its key points here. If the budget measures were adopted, Whiteford reports:

- An unemployed twenty-three-year-old would lose $47 a week, or 18 per cent of his or her disposable income. An individual earning $250,000 a year would lose $24 a week, or less than 1 per cent of disposable income. Is that fairness?

- Unemployed people aged under thirty, who receive less than 1 per cent of budget spending, would suffer almost 10 per cent of budget savings.

- The National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling calculates that the poorest 20 per cent of households, which earn 8 per cent of all household income, would shoulder 16 per cent of the budget cuts. The richest 20 per cent, which earn 40 per cent of all household income, would shoulder just 10 per cent of the cuts.

If the government really wanted to close the budget deficit, why did it weight its cuts to fall so heavily on lower- and middle-income Australia, and so lightly on its own class of upper-income Australians? Did it not foresee the public reaction?

If it was serious, why didn’t it come up with a comprehensive deficit-reduction strategy that tackled both sides of the ledger – increasing revenues, since that is where the real problem lies, as well as reducing spending? That would ensure that the pain was minimised by being shared by all, including those best able to pay. That would work to unite us, rather than divide us.

The only unity Australians have gained from this budget is in opposing the lot – the good along with the bad. This week Essential Research published a new poll that found Australians oppose all six budget measures on its list, mostly overwhelmingly. Only 18 per cent support indexation of petrol tax, 20 per cent support cuts to university funding, 24 per cent support the $7 Medicare co-payment, and so on.

Back in October, Essential found Australians supported only one measure on a different list of budget savings: sadly, cuts to foreign aid. Only 25 per cent supported the first lot of cuts to the ABC, only 28 per cent agreed with a higher pension age, and only 12 per cent supported the central measure intended to reduce the deficit: taking $80 billion from future school and hospital funding for the states.

According to the old political wisdom, governments planning reforms should do them all at once, so that no one issue can get the airplay to stop it. That maxim now needs two qualifications: the government must start with strong public credibility and an ability to sell its message.

This government had neither, and still hasn’t. Since the budget it’s gone quiet on the plan to shift schools and hospitals spending to the states, yet that is the cornerstone of the deficit-reduction strategy. Without it, there will be no deficit reduction. Presumably the government is waiting until after the NSW and Queensland elections, so as not to embarrass its state allies.

Nor has it campaigned to explain why we should increase the pension age or index fuel taxes. The Australian’s Paul Kelly berates voters for not realising that the budget is in crisis, but the government’s actions suggest it doesn’t itself see it as serious. That much is clear from the detailed numbers in its two budget exercises so far – the 2013–14 MYEFO and the 2014–15 budget. They are summarised in the box below.

The bottom line is this. Had the Abbott government’s spending cuts been implemented, they would have cut budget deficits by $70 billion over four years. Its tax cuts and new spending, meanwhile, would have added $67 billion. Net saving: $3 billion over four years.

Some budget emergency!

To put it another way, even in May, the plan was for 96 per cent of all the money saved by the Coalition’s spending cuts simply to be spent in other ways. Only 4 per cent was to be used to reduce the deficit.

Under Labor’s policies, Treasury estimates, the cumulative deficit for the four years from mid 2013 to mid 2017 would have been $110 billion. Under the Coalition’s policies, it would be $107 billion.

And that was in May: before the new commitment of troops to Iraq, before the free-trade deals, before the extension of the royal commission into the unions, etc., etc. Even if the Senate passed all the budget measures it has rejected, the new MYEFO will reveal that the net result of the Abbott government’s decisions has been to increase the deficit from what it would have been had Labor’s policies continued on autopilot.

These are the budget’s own figures. All I’ve done is to add them up – and add the $1.2 billion costs of servicing the increased debt resulting from its tax cuts and new spending.

Between them, the 2013–14 MYEFO and the May budget handed out $45 billion of new spending over the four years to 2016–17, and $22 billion of tax cuts – all funded by taking on new debt. Three decisions accounted for half of them: scrapping the emissions trading scheme ($13.7 billion), the splurge on new roads ($12.1 billion, without any cost-benefit analysis) and the $8.8 billion grant to the Reserve Bank – a grant the RBA had not asked for, and which appears to have been designed to inflate the 2013–14 deficit and lay the blame on Labor.

That was not the only fiscal fix. During the Victorian election campaign it emerged that Hockey prepaid the Victorian government $1 billion for the East-West Link in June – so that it could appear as spending in 2013–14 (blamed on Labor) rather than 2014–15 (for which he must answer). Victoria, of course, didn’t spend the money, just banked it. MYEFO 2014–15 will show if there were other fiscal fixes like that one.

One caveat: in the longer term, if the government’s budget plans were all implemented, they would reduce the deficit significantly. Its strategy has been to load up the deficit in 2013–14, and reduce it in later years. By 2016–17, Treasury estimates, the net impact of the government’s policy changes would lower the budget deficit by $9 billion, including $6.4 billion saved that year alone by cutting social security payments.

Eventually the budget would get back to surplus, primarily as a result of increased income tax revenue from bracket creep, and the savings from the government’s plan to cut $80 billion from grants to the states for schools and hospitals.

But the Commonwealth could never win an argument with the states on those cuts; it would be seen as abandoning its responsibilities in two crucial areas of government. It could win only if the states collectively decide they would rather have a bigger GST to spend as they choose than have the Commonwealth share the cost of running schools and hospitals. And premiers get to be premiers because they’re good at politics.

The Abbott government could try to keep fighting the same old issues, but the polls suggest the voters have stopped listening. It still has twenty-one months left before it has to meet its electoral fate. It could turn off the life support for the old budget plan and reboot with a new comprehensive strategy – closing tax loopholes as well as cutting spending – clearly designed to reduce the deficit rather than pay out on political enemies (including students and universities, the ABC, foreign aid and welfare groups, and public transport). It would have to unite the country behind a common purpose, rather than divide it.

But Tony Abbott by nature is a cultural warrior, not a unifier: that’s just not him. If the Coalition is to adopt a budget strategy to win over the middle ground, its Cabinet reshuffle has to start with him. I can’t see that happening. •