Clade

By James Bradley | Hamish Hamilton | $32.99

All of us have moments when we notice unexpected changes in climate or the loss of familiar aspects of the natural world, but these can press in more urgently at some times than at others. The apocalyptic bushfires in Canberra in 2003 and Victoria in 2009, the massive drought-induced dust storms, the more recent floods – all of these gave Australians enough of a fright to make climate change a major political concern. But a relatively benign summer can calm our fears and make us view those shifts as part of a natural cycle. Back in the 1970s, many of us thought that oil resources would be depleted by 2000. We were wrong about that – so maybe we can just go along with the flow of climate change, so to speak, and accept that the natural world will sort itself out.

James Bradley’s novel, Clade, seizes on our capacity to forget past concerns or lose account of them. It looks at the way our absorption in day-to-day life can mean we are unable to see the whole scheme of things. Many of the changes in the natural world are incremental and easy to overlook; it can take a catastrophe to draw our attention away from our personal concerns. And even the scientists documenting the small changes in our world may not live long enough to see their full implications.

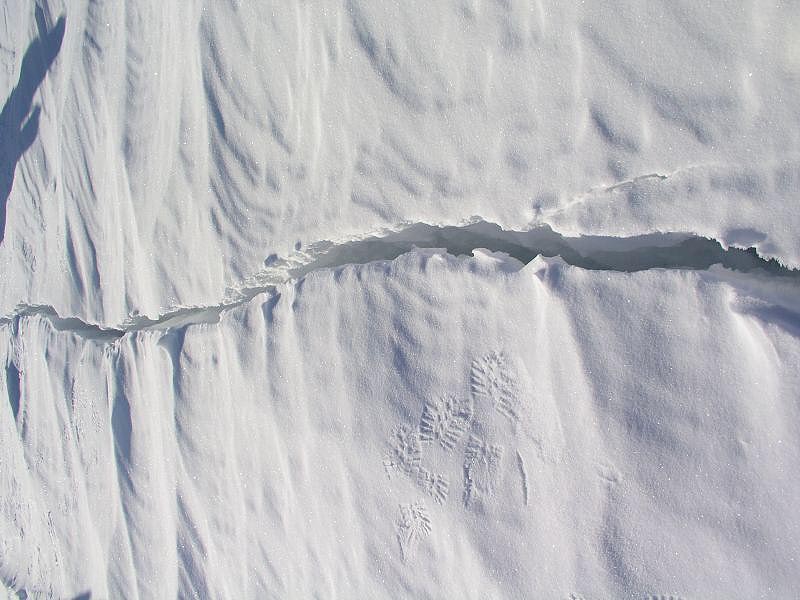

Clade follows an Australian family over decades – into the future of the 2060s – to speculate about how the combination of small losses and catastrophic events might realign our world. At its beginning, set close to the present, Adam Leith is a biological scientist examining the evidence of past climate transformation in Antarctica. He is also worrying about his partner, Ellie, who is undergoing various medical procedures in an attempt to conceive a child. Amid ominous signs – a mighty crack as “the entire landscape on which they stood slipped and fell towards the sea” – Adam is philosophical about the melting ice and about the crisis in his personal life: “What else is there to do but hang on and hope?”

A few years later, Adam and Ellie are the parents of a toddler, Summer, who suffers a severe asthma attack as they cope with yet another power blackout as a result of fires. Adam is working on modelling the decline of the South Asian monsoon, and his colleagues in New Delhi feel a “frightening urgency” about the project. In Australia, it seems, people simply adjust to the inconveniences of unreliable power. And so the novel gently expands many of our current concerns – the loss of crucial parts of the ecology, the arrival in Australia of homeless people from other continents, the threat of natural disasters – to the point where they have begun to change the possibilities for freedom, let alone social cohesion.

Much later, Adam and Ellie’s grandson Noah is an astrophysicist searching the constellations for signs of life, knowing he can’t live long enough to learn what his instruments have found. This episode underlines one of the main emphases of the novel – that our lives are not long enough for us to see large patterns or understand the shifts in our universe.

Clade follows Adam’s life from about 1990 to 2070 or thereabouts, so he lives to the full expectation, surviving all the disasters that impinge on his world. He is aware of the damage to the earth, and occasionally furious with the climate deniers, but powerless to interrupt the steady destruction of the natural world we know. Yet events in this novel are not apocalyptic. Even a devastating tidal flood that he, Summer and Noah survive in the tropical England of the 2040s appears – like the recent hurricanes in the northeast of the United States – to be just another catastrophe to challenge the resourcefulness of people and governments.

The changes the novel imagines are so plausible and so gradual that it hardly seems like science fiction. Technology certainly progresses – an internet/virtual reality system that can operate reliably in all kinds of extreme situations is accessed by “overlays” – and war seems to have diminished as the peoples of the world try to cope with their changing environments. The family at the centre of the novel suffers hardship and loss, but manages to survive more or less intact, possibly because of their advantages as educated, middle-class Australians.

Clade doesn’t explicitly connect the changing environment with infertility, asthma, childhood cancer or autism but those conditions form a clear pattern in the story. It glances, too, at the once-popular idea that we should have fewer children to save the planet, reminding us of the high expectations we’ve developed about infant survival and universal entitlement to parenthood. The desire of the women characters, in particular, to have children appears to be a biological drive in the face of threat, further evidence of the way the personal responds to the universal.

Bradley has taken on the challenge that climate change presents to artists: how to create fiction that is true to the scientific facts while imagining their effect on individual humans, and how to do that without overstating the case. For the most part, he manages to avoid the sense of jeremiad, carefully allowing the familiar problems of family life to foreshadow the impending crisis. Ellie is a visual artist and, at the beginning of the novel, it appears that her art may offer insights into the history of the natural world, but Bradley leaves her behind to follow Adam’s scientific work – as if he accepts that the artist’s engagement with the crisis cannot match the importance of science. All her beautiful creations can do little to help, and yet Adam’s scientific work seems to gain little traction either.

The novel manages the passage of time by presenting a series of fairly discrete episodes, usually in present tense and often from Adam’s point of view. Bradley introduces peripheral characters to cover his range of concerns – the daughter of Noah’s carer, Lijuan, writes a Journal of the Plague Year while her boyfriend, Dylan, is the narrator of a section on memorials for the dead – which means that a relatively short novel can cover leaps of time and explore many ideas. The sacrifice, of course, is in the character development: each serves the larger purposes of the novel rather than taking on clear and engaging personalities of their own. Ellie is already remote and self-absorbed by the time the novel begins, and her mental condition is reflected in her daughter Summer’s sullen refusal to communicate and Noah’s diagnosed position on “the spectrum.”

Bradley may be suggesting that this withdrawal from relationships is a likely outcome of all the time we spend absorbed in screens and unable to confront the world around us. Or perhaps the withdrawal is a human reaction to anxiety about events in the larger world. Either way, it creates problems for the novel: the central characters become relatively silent and unknowable, their dialogue limited to the most basic conversations.

Bradley is at his best in describing the changing world – the landscape on the drive north from London with its genetically engineered trees, Ellie’s work on her bee installation, Noah’s excited engagement with distant constellations, the beauty of the natural world even as its features become more extreme. It is this sense of wonder that provides the slight feeling of hope at Clade’s conclusion. The book’s speculation about the gradual nature of change and the possibility that we may cope with it incites an optimism that is, of course, part of that human capacity for adjustment and forgetfulness. •