The Australian is an odd beast. One of the youngest of Australia’s newspapers, it nonetheless has the look and feel of an old man’s paper (well, it comes out in paper form for a start!), which perhaps reflects its readership. But it goes on appearing each day despite all the obvious reasons why it might not. It is not widely read. It is not very profitable (to say the least). But it does make one claim for its significance – it is influential. While there is no doubt that this is true – in part – it is a claim that needs to be examined more closely than it usually is. In what ways is the Australian influential? Upon whom? Here I am interested in what has been, since 1970, one of the most successful reform movements in Australian history: the gay equality agenda. What has the Australian contributed to this struggle; and how has its support and opposition mattered?

The Australian was born in 1964, at the very moment when deep-rooted pressures for change in Australian society were starting to manifest themselves publicly. The newspaper was both an expression of the emergence of a modernising liberalism (captured best, from a historian’s point of view, by Donald Horne’s Time of Hope), and a booster of those changes. It was a liberal paper and was interested in promoting new ways of thinking about issues that had been around for some time, and in talking about issues that had not previously been on the public agenda.

On 27 July 1964, two weeks after its first edition, the paper ran a news article entitled “Students Vote for Legal Homosexuality,” which reported that the Melbourne University Debating Union had, the previous day, voted 203 to twenty-seven that homosexual acts between consenting adults ought to be decriminalised. The paper reported both sides of the debate, but presented the “yes” case in much greater detail. Not content with that, the following day it reported that four public figures, who had presumably been approached by a journalist, had agreed with the 203 students – including no less a figure than the Anglican archbishop of Melbourne. (The others were a professor of philosophy and the warden of St Paul’s College – both at Sydney University – and the president of the NSW Humanist Society.)

In the letters that followed, one correspondent, who identified as a homosexual but wrote anonymously, pointed out that as little as a month before no newspaper would have touched such a subject. The author of the letter was right. What made the Australian’s article notable was not that this was the first news story in a mainstream paper about homosexuality (it wasn’t), but that it treated the story outside the usual frame of homosexuality-as-a-problem. It was the student vote on a controversial issue and the response to it that was news, not the homosexual as such.

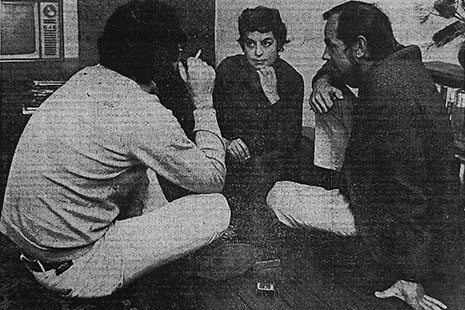

There was not much published in the following years, but that was mostly because there wasn’t much news to report. All that changed when homosexuals began to speak for themselves, starting in 1969 with the establishment of the lesbian organisation Daughters of Bilitis in Melbourne and the Homosexual Law Reform Society in Canberra. But the most important event of this period was the formation of Campaign Against Moral Persecution, or CAMP, by a small group of activists who decided in early 1970 to establish an organisation to monitor and respond to media misrepresentations of homosexuals and homosexuality. A letter was drafted and sent to the press – and a number of papers duly published it. Adrian Deamer, then the editor of the Australian, and one of the profession’s best, decided instead to send a reporter to talk to the founders of CAMP. On Saturday 19 September, in a page-and-a-half spread under the title, “Couples,” John Ware and Christabel Poll talked about CAMP and their lives as homosexuals. They used their full names and were photographed full-face.

The effect was electric. Homosexuals and heterosexuals all over the country were presented with something that had never appeared in print before – completely open (“out” as we would later say) gay people, presented as perfectly ordinary citizens whose only real point of difference was whom they chose to have sex with. Within days, letters started to arrive for the organisation, and within a year, this little group was a national organisation with 1800 members, branches in all capital cities and on most university campuses, a newsletter and clubrooms. It was the launching point for the kind of gay politics that are with us still. Newspapers, magazines, radio and even television rushed to interview homosexuals and to report on this new-found minority.

The catalyst was the Australian. Deamer’s decision to make more of the issue than other papers had done, the Australian’s national audience and the extensive coverage on a Saturday gave the group and homosexual politics a start that no amount of money could have bought.

And yet, while the paper’s contribution is undeniable, it was the prominence it gave to the issue that was different, not the fact that it covered the issue at all. The willingness to talk about homosexuality in a serious way was emerging in the smaller-circulation Australian press at about this time – in alternative outlets such as the Humanist and the civil liberties newsletters, in the student press, and in the Bulletin, Nation and the Australian Book Review. It was only a matter of time before the mainstream press – the Age and the Sydney Morning Herald, most obviously – began to join in. (The Canberra Times moved early – reporting extensively on the Homosexual Law Reform Society from the organisation’s founding in 1969.)

The Australian’s role was to bring to the attention of tens of thousands of people an issue that had previously been known only to much smaller numbers. It spoke to, and reinforced, the modernising liberalism of the audience that the Australian was cultivating, and in so doing undoubtedly served to advance those politics strongly. But if the Australian hadn’t existed, developments would not have been significantly different.

Repeatedly over the 1980s, the issue of decriminalisation arose, as each state grappled with the question of whether men ought to be allowed to have sex with each other. Alongside it, the expansion of the gay agenda into the field of anti-discrimination against individuals and couples ensured that gay issues remained in full sight. The Australian’s approach to all this was cautious but supportive.

And then came AIDS – a real test for the Australian media. The first reports of this virulent new disease came in the gay press (which was obsessively interested in US gay life); the mainstream press in Australia started to report on what it was inclined to call “the gay plague” in 1982 and early 1983, and then only spasmodically.

On 28 June 1983, in the same issue that reported the first Australian to die of AIDS, the Australian editorialised under the headline “No Need for Hysteria.” It argued against any sense of panic, rejected the idea that this was a twentieth-century Black Death, and denounced the views of those who saw in the disease any evidence of biblical visitation. Only the “coldly clinical view of the medical specialist” should carry any weight in the community, said the paper. Despite this, the Australian went on using the phrase “the gay plague” for longer than many other responsible papers, and one letter it published criticised its coverage as “inflammatory, alarmist, moralistic,” noting that it had ignored the press release of the recently formed AIDS action committee. Another noted that the paper seemed happy to report Fred Nile’s alarmist and homophobic comments.

On 25 August 1984, the Australian published an editorial, “AIDS and the Gay Community.” It expressed sorrow about AIDS and its impact on gays, noting that the disease had appeared – and with it the risk of a public backlash – just at the time when gay people were starting to gain acceptance. But the editorial focused most on the medical threat, observing that it was one of many that had surfaced recently (toxic shock was another, for example) and asserting its optimism that cure and treatment would not be far away. The call for calm is the dominant note. It came on the same day that Neil Blewett, federal health minister, was reported (widely) as having criticised talk of an epidemic and lamented the emergence of panic, blaming “irresponsible and sensational publicity.” (That a leading politician speaking out against public panics and the media campaigns that promote them might come as a surprise points to the degeneration of public debate and political leadership in more recent times.)

Generally speaking, the Australian held to a responsible line over the coming years. The paper’s general promotion of calm and reasoned debate, and its opposition to discrimination, was perfectly in keeping with one strand of the mainstream media’s work in the 1980s and 1990s. But it maintained in its stable of writers people such as B.A. Santamaria and Father James Murray, who could be relied on to provide a more inflammatory take on public events, including those concerning gay people and HIV/AIDS.

The real test for the claim that the Australian is a paper of influence comes with the debate over gay marriage. In 2003, Canada started to recognise same-sex marriage, and Australians with Canadian citizenship were being married and expecting to have their relationships recognised on their return, as was the case with opposite-sex marriages. John Howard moved fast and, supported by the Labor Party, legislated reforms to the Marriage Act to make it clear (as it had not been to that point) that marriage was a contract between one man and one woman. A further clause made it clear that overseas marriages between people of the same sex could not be recognised here.

The Australian, its neoconservative turn by this time thoroughly embedded, moved as quickly as Howard and Latham to express its opposition. On 27 February 2004, it editorialised under the headline “Same-Sex Marriages Not on the Agenda.” Focusing on the debate in the United States, it declared that the issue was more “Machiavelli than marriage” (that is, that it was a matter of politics rather than human rights), that it was not an issue here in Australia (a claim rather belied by the publication of the editorial) and that it was not a debate that we needed to have. Marriage was not a “first-order problem,” and most people in Australia saw it in exclusively heterosexual terms. Same-sex couples had the right to live together in a permanent relationship, should have the same property rights as opposite-sex couples, and were able to celebrate their commitment in any way they chose (except in marriage, of course; a point the editorialist did not make). “Gay activists who think this is a form of discrimination should get over it and focus on practical issues,” it insisted, and same-sex couples should resist the politicisation of their private lives by pro- and anti-marriage activists.

Two months later, on 28 April 2004, the editorial’s headline read “No Bouquets Needed for Gay Marriages.” By this time the editorialist (clearly also the author of the previous effort) had come to terms with the fact that it was an issue and needed to be debated. There were a couple of shifts in the line of argument – instead of activists trying to politicise gay lives, it is the same-sex couples who believe that they are being discriminated against who should get over it; and the tone is noticeably more strident – although juvenile might be a better word: “Political wizards who want to raise an electoral storm… conjuring up a phoney debate,” and so on.

These two editorials set the line of the Australian for the duration of the debate, except to the extent that changing circumstances undermined some lines of attack. The idea that public opinion was not onside with gay marriage lost its validity rapidly. (Indeed, one of the remarkable features of the same-sex marriage debate is the extent to which the Howard–Latham legislative coup started a process during which support for same-sex marriage grew steadily.)

The Australian’s editorial team came to rely on three arguments. One is that only the “traditional form” of marriage should be legal. This cracked apart as it became clear that for most people the traditional form of marriage involved an expression of love and commitment between two people made by a formal ceremony in front of their friends; that the couple were of the same sex was an innovation, no doubt, but not a violation of how most people saw the matter. Faced with family, friends, colleagues wanting to marry, most Australians seemed to find it hard to think of a reason why they should not be allowed to do so.

(The theologically inclined – of which the Australian seemed to have a strong representation – saw marriage in biblical terms as a sacred and holy union in which a man and a woman became “one flesh.” But in a radically secular country they could hardly go public with that particular line of argument, or have much influence with it if they did.)

Then there is the argument that same-sex marriage is not a first-order issue. In a world wracked by climate-change, inequality, poverty and decaying democratic structures, this is, of course, true. But it is a first-order issue for those committed to fighting for it and it is hard to see them adjusting their political priorities on the Australian’s say-so. And as for the politicians to whom the Australian speaks so stridently – it is likely that at some point (probably sooner rather than later) they will decide to just do it and get the damn issue off the agenda.

Finally there is the argument that Labor’s support for same-sex marriage (however half-hearted it might be) was undermining the party’s standing among its working-class base. There is not a shred of evidence for this. Even the party has never publicly pushed that claim to make its case, and I know of no opinion polls that show that opposition to same-sex marriage is disproportionately concentrated among working-class people, who are just as likely to have gay family and friends as anyone else. (My guess is that the hardcore 30 per cent who are opposed represent the smaller religious denominations disproportionately.) It is worth remembering that after the restoration of Kevin Rudd to the prime ministership, while he was furiously pandering to the (perceived) xenophobia of (sections of) the electorate in relation to refugees, he quite loudly declared his conversion to support for marriage equality. And Julia Gillard’s opposition speaks more to her dependence on right-wing party factions than to any genuine opposition to such marriages.

If the Australian had hoped to demonstrate its influence via this issue, it has done precisely the opposite. Support for same-sex marriage is now higher in Australia than ever before and as a reform it is pretty much unavoidable.

Indeed, this is a fight the Australian should never have picked. It flies in the face of what Australia is, and is becoming, in a quite remarkable way. When the Australian rants against the modernisation and liberalisation of Australian society, when it engages in contemptible smear campaigns against people like Larissa Behrendt – whose supporters it abuses (as Chris Graham has documented) as mere academics, lefties, progressives, Aboriginal sophisticates, elite activists – when its team denounces feminists as The Sisterhood, and others as cosmopolitans… when it does this, it is arguing against the very nation it has otherwise done so much to help create.

The neoconservatives want free markets, economic liberalism and individualism alongside a moral order that privileges what has been over what people are now choosing. If the gay agenda has gone too far, where should it have stopped? If our moral order is a product of a demonised 1960s, is the alternative a return to the 1950s? If university education corrupts the minds of those who get it (and it does in that it promotes critical thinking), should we scale it back? The sin of the cosmopolitans is to be engaged with the rest of the world. Is there any alternative to this?

Under Chris Mitchell (and his boss), the Australian has, on social questions, become the voice of grumpy old men, railing against the way things are these days. Perhaps they should accept that on gay equality we have won and they have lost – and get over it. •