Gallipoli

By Peter FitzSimons | Random House Australia | $49.99

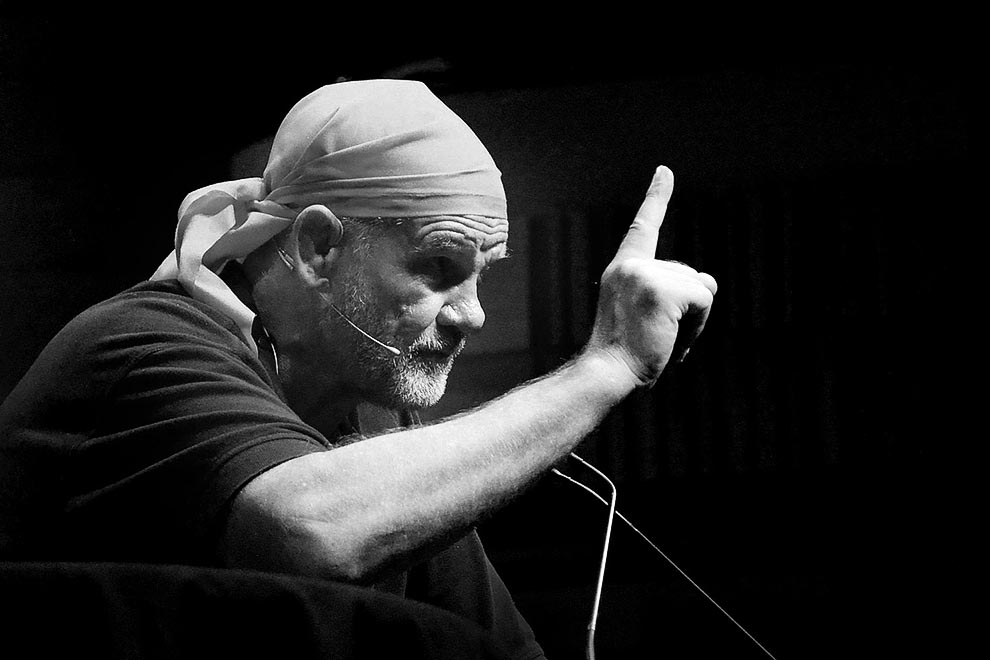

Many years ago – before he became a “storian,” and possibly even before he wore a bandana – I read a book written by Peter FitzSimons. It was 1998, and the book was a conventional biography of Kim Beazley, who was the opposition leader at the time. I suspect it didn’t sell a huge number of copies but it was a competent and judicious effort. Some time after that, “Fitz” (I reckon he almost demands to be called that these days) found that he would sell a lot more books if he adopted a style that made readers feel as if they were right in the action; “like the Red Baron’s co-pilot” is how he phrases it.

Reading Fitz’s latest book, Gallipoli, confirmed my view that he didn’t need to flick the switch to vaudeville. There is enough solid historical research and sustained writing in Gallipoli – including about what happened on the Turkish side – to satisfy most discerning readers, provided they can get at it among the other stuff. Large sections of the book are marred by AUTHORIAL PESTERING (including egregious font changes and capitalisations) and heavy-handed pointers about how the reader should respond to what he or she is being told by the author. Time and again I was just starting to get absorbed in FitzSimons’s writing when, out of a trench or from behind a metaphorical bush, Fitz would leap like Jack Nicholson in The Shining. “Gawd help us all,” “Tricky buggers!” “Hurrah! Hurrah!” “Outrageous” and “Yes, mate, you’ve done your duty” peppered the pages. In the most frenetic chapters, like the ones describing the landing on 25 April, this poltergeist was fairly hopping.

If this manic character had had additional dialogue written for it, it would have been along the lines of “Did you get how horrible that last bit was?” or “Pathos coming up here, Dear Reader” or simply “Look at me, look at me!” (When Fitz spoke last year in Canberra about his latest book, his well-honed opening remark was that, while there had been lots of books written about Gallipoli, “Guess what? I haven’t written one!” The crowd loved it.) I’ve read an awful lot of non-fiction books, including many where it is clear that the author is passionately interested in his or her subject. There was Clare Wright in The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, Joan Beaumont in Broken Nation, Paul Daley in Collingwood: A Love Story and Peter Stanley in Black Saturday at Steels Creek, all books where the authorial presence was palpable. Yet I’ve never cringed at an author’s antics like I did at Fitz’s in Gallipoli.

In some ways, Fitz’s book is more like a biography (of the place, Gallipoli, and how it overwhelmed the humans who clung to it) but my comment applies equally to that genre. Even Edmund Morris, inventing a character in Dutch to try to get closer to the enigmatic Ronald Reagan, wasn’t as annoying as Fitz is in this book. The Gallipoli story, of all Australia’s many stories, least needs a Chorus.

Commitment to one’s subject matter shouldn’t require the author to be all over it (and the reader) like a rash or to wear his heart on his sleeve so much. “I weep,” he writes, at the fate of Hugo Throssell VC (though a few pages earlier, he misplaced the mother of Throssell’s dead NCO, Sid Ferrier, my great-uncle, in Western Australia, rather than Victoria). The Red Baron’s co-pilot might have shed a tear at that point but this Dear Reader just thought “too much altogether.” The reader can be brought to his or her own conclusions – by the laying out of hypotheses and evidence – about the fate of Throssell, or anyone else, without clunking hints like that.

Dear Reader can even be encouraged towards the same conclusions as the author draws but without the need for regular whacks on the head. Evidence expertly led always trumps primary sources plonked down in wodges and linked by authorial ejaculation. (I use that word in the sense that Enid Blyton often did, as in “‘Gosh, Dick, this is a scrumptious ice!’ Julian ejaculated.”) The depth of an author’s feeling for a subject shouldn’t be measured by the number of exclamation marks scattered across the page. The persistence and intensity of the authorial intrusions in Gallipoli are such, indeed, that one is inclined to attribute them to affectation rather than enthusiasm. This is Fitz playing to the fans.

When the man in the bandana restrains himself, though, as he mostly does in his description of the truce of 24 May and the evacuation in December, to give two examples, he shows himself to be approaching a fine writer. Fitz the storian becomes more like FitzSimons the historian. I did weep at his description of the evacuation and the feelings of those who were leaving mates behind, but at that point I was not an author telling readers how to react but a reader responding to a historian effectively plying the historian’s trade.

Russell’s Top, opposite the Nek, is the last occupied frontline post [FitzSimons writes]. It has been so hard-won, with so many Australian lives lost there that it is hard to leave, but, at exactly 3.14 am, the raggedy remnant of the 20th Battalion, those phantoms of the trenches, turn on their padded heels and walk away…

Much of the rest of the book, however, is marred by what I talked about earlier. Overwritten paragraphs, often splutteringly so, excessive quotation of sources rather than letting them speak in a way that supports an argument (or paraphrasing them to the same end), Fitz leaping in with a nudge or a wink about what it all means – all when a more careful (and confident?) author might have presented a judicious, possibly slightly qualified conclusion on the basis of evidence.

Fitz says he eschews drawing conclusions in the way that historians do. But don’t be fooled by this claim into thinking that he does not take positions. The book reeks of themes: heroism, blood and guts, sacrifice, patriotism, sudden and unexpected death. Try these for size:

“[B]lood momentarily spurts from the soldier’s head just before he dies with a snapped neck.” (There is an endnote making clear that there is no evidence that this happened on the particular occasion, merely an assumption by the author, based on medical advice.)

“Dead bodies begin to wash up on the shore, their hands all too frequently reaching for the solid land, their legs bobbing in water red with blood.”

“[W]ith a sudden crash, the sub hits the banks of the eastern shore. Oh… Jesus and Mother Mary… have mercy.”

“[H]e has just killed a man – put his bayonet right through him and sent him from this earth.”

Realism in war writing is a good thing, of course, but realism in this book too often slops over into ghoulishness, mawkishness and, occasionally, jingoism, while mostly stopping short of considering why all this blood was being spilt and whether it was worth it. The epilogue of the book, where Fitz might have chanced his arm on bigger questions, is mostly standard “what happened to” tying up of loose character ends.

Fitz has been well-placed on the Council of the Australian War Memorial, an institution that has a similar cockeyed appreciation of war. (Masses of sentimental memorabilia on what happened, very little on causes and impacts.) Fitz’s welcome activism in other causes, such as the Republic, flag reform, sexuality and gender, and abuse of children by teachers, is offset by his fellow-travelling, witting or unwitting, in Anzackery, the overblown commemoration-celebration of Australian military history and the most conservative and least questioning of our national obsessions.

In many respects Fitz’s Gallipoli reminded me of W.H. Fitchett’s (Fitch’s?) Deeds that Won the Empire, written to “nourish patriotism,” published in 1897 and reprinted twenty-nine times around the world before 1914.

What examples are to be found in the tales here retold [writes Fitchett], not merely of heroic daring, but of even finer qualities – of heroic fortitude; of loyalty to duty stronger than the love of life; of the temper which dreads dishonour more than it fears death; of the patriotism which makes love of the Fatherland a passion.

As in Fitz’s Gallipoli, there is no lack of blood and guts in Deeds (“Die hard! my men, die hard!” “One private reached the sword-blades, and actually thrust his head beneath them till his brains were beaten out.”) but a bloody death is honourable, particularly if one lasts long enough to leave some inspiring final words. Taking a cue from Fitch’s patriotic potboiler, Gallipoli could be subtitled “deeds that birthed a nation” and Fitz is, for now, close to being the Fitch of the twenty-first century.

Like Fitch also, Fitz misses nuances, such as the rise and fall and rise again of Anzac over a century, a trend that Carolyn Holbrook documented in Anzac: The Unauthorised Biography. Compare Holbrook with Fitz’s couple of lines on page 687 about a tradition that allegedly has grown steadily from the 1920s and left each one of us ever since with “a naturally bowed head” regarding Anzac Day. Our changing national mood about Anzac is a pretty big nuance to gloss over; perhaps Holbrook’s book came out after the Fitzian research team had knocked off, though Holbrook is by no means the first writer in this field.

One could challenge FitzSimons, for the purposes of a future book, to heave the reader out of the Red Baron’s plane – a colleague points out that the Baron’s Fokker Dr.I only had one seat anyway – and let the author’s suppressed historian glands suppurate a bit more. The poltergeist has given plenty of hints that he has more under the bandana – perhaps a pair of brains – than he mostly lets on. I hope Fitz is not even more hooked on the current formula than his tens of thousands of readers are. (It must bring in a motza. Fitz’s website says he has been Australia’s best-selling non-fiction author in the past decade.) That would be a pity, because we need all the historians we can get.

Storians should stick to writing comics. Fitz’s claim to be just a storian is a form of reverse snobbery. Fitz sells FitzSimons short. Fitz should let his inner historian blossom, even if he has to take considerably longer honing his books. The fans looking for a Fitz for Christmas can always fall back on Stephen King. •