Sixteen years ago, during the 1992 US presidential election campaign, Bill Clinton would fire up rallies with the slogan, “It’s the economy, stupid.” Such a simple phrase, yet somehow capturing the mood for change, it built momentum and left crowds roaring.

If you can remember this, your memory is faulty. “It’s the economy, stupid” was not a campaign slogan, but a note on the wall in Clinton’s headquarters; its purpose was to keep the troops focused and prevent them getting side-tracked by less important issues. It was made famous by the fly-on-the-wall documentary The War Room, but it was not at the time meant for public consumption. Yet in the collective memory it has become something it was not.

History can be like that – just plain wrong. More often, it is a bit dodgy, with the wrong emphasis or important facts left out. But that’s always a matter of opinion.

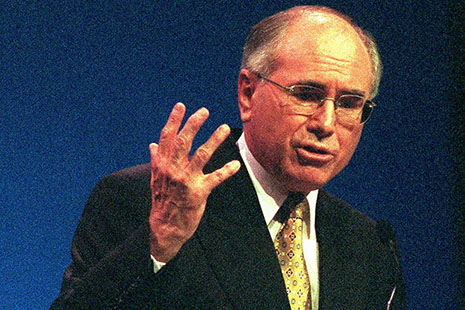

The Howard Years – four fifty-minutes episodes, of which the ABC has screened two – is a bit dodgy. For one thing, it has the tone of the early Howard years all wrong because it views them through the prism of the later ones. It’s like remembering a deceased friend as you last saw them, recalling that old person enacting their youthful endeavours.

It is fair to say that from late 2001 John Howard was widely seen as a strong leader, a “conviction politician” – in George Bush’s words, a “tough little dude.” The genesis of this persona was in the Tampa “crisis,” and it was consolidated by the “war on terror” and Iraq. But the first two terms, 1996–98 and 1998–2001 were, as anyone with a clear memory (or access to newspaper archives) knows, very different.

Like many new governments (including the current one) Howard and his colleagues took a while to find their feet. They seemed at times not to be sure why they were there. Like Kevin Rudd, Howard had promised before the 1996 election, in so many areas of policy, not to change anything, leaving little room to move. Also like Rudd, Howard appeared rather timid politically, seemingly unaware of the strength of incumbency.

Yet the first two episodes of The Howard Years apply the “conviction” template to the actions of the young Howard government. This makes for some lines preposterously at odds with reality. Narrator and interviewer Fran Kelly informs us that Howard came to power with a “mission to recast Australia.” In early 2001, she tells us, when opinion polls appeared diabolical, “some might have been rattled, but not John Howard.” The “Man of Steel” is a continuous presence.

For a more realistic view, here was the judgement of the Australian’s Paul Kelly at the government’s first anniversary in March 1997: “During the 1980s there was an orthodoxy about Howard – that he was the reforming spearhead of the Coalition, but weak on politics. Yet the orthodoxy today is more likely to be the reverse – that Howard is an adept politician with doubts about his ability to implement genuine change.”

And things only got worse from there. As the conservative commentator Michael Duffy wrote in the Daily Telegraph, urging readers to vote for Howard before the 1998 election: “Howard does not seem to have leadership qualities. He lacks the ability to inspire… He simply doesn’t rise well to some of the challenges of leadership.” (But vote for him anyway, wrote Duffy, because Kim Beazley is even worse.)

From late 2001, no commentator would have written such things about Howard, because he had come to be seen as strong and decisive, someone who speaks his mind. Up to that point, not even his greatest supporters would have called him “Churchillian.”

The second episode of The Howard Years improved on the first, mainly because it devoted substantial time to a matter of substance – the accidental policy of independence for East Timor. The GST negotiations with the Democrats, with prime ministerial staffers frantically searching for herbal tea, were good fun. The coverage of the Tampa was also interesting, but tiptoed around the political angle: here, once again, was a conviction politician doing “what was right,” with no mention of the electoral considerations that fuelled intemperate language from Howard and his immigration minister, Philip Ruddock.

An obvious comparison is with Labor in Power. In that 1993 ABC series, the major players – Bob Hawke and Paul Keating – were, as you would expect, determined to push their versions of history. But lower down the food chain, ministers and staffers were often much more relaxed, flippant and candid, which must have made for hundreds of hours of excellent raw material for the editing suite.

By contrast, everyone in The Howard Years is relentlessly on-message. Peter Costello’s advisor Tony Smith gravely informs us that his boss was “ashen-faced” upon discovering the true fiscal situation inherited from the Keating government. Costello agrees, adding that they were willing to lose government if that was what it took to fix the budget. This political spin 101 is presented with a straight face, and no correctives. Everyone’s words are taken at face value. And everywhere we turn is the Man of Steel.

Why is this series such timid television, so scared of offending? Gerard Henderson suggests that the show “breaks little new ground – perhaps because the interviewees did not feel that Kelly is empathetic to their positions.”

This is probably true. Like most journalists, Fran Kelly comes across as “a bit left-wing.” Liberals tend to be suspicious of journalists for this reason, and when those journalists work for our ABC, that suspicion multiplies. The participants in Labor in Power probably felt relaxed enough to be relatively frank without fearing they’d have a job done on them. But those who were interviewed for the current series might not have thought the producers would give them a fair shake. Terrified of finding a misspeak blown into a headline, they stuck to the script.

This would have given those putting the show together less interesting raw material, but somewhere in the production process the problem seems to have been exacerbated. I suspect that the ABC was so eager to avoid allegations of bias that it erred on the side of caution, accepting everything their Liberals said at face value, even the flakiest spin. This must also be why we see and hear so much of Howard’s best friend Graham Morris, who stopped working for him in 1997 but appears to be on hand for the whole series to keep the story on track.

In an ABC series called The Liberals, screened in 1994, the interviewer and narrator was the high profile journalist and now NSW state Liberal MP, Pru Goward. Her interrogations elicited much more candour than this one, no doubt because her presence elicited trust. And maybe the ABC did not feel so under siege in those days, or perhaps having Goward on board gave them more breathing space, but those producers were able to stick together a show with flesh and blood and correctives and three dimensional characters.

So far, The Howard Years has offered little complexity. A combination of forces has flattened its narrative. But maybe the final two episodes will be different. •