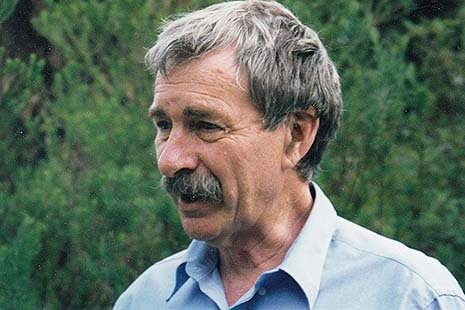

The boy from Boort | Ken Inglis

I FIRST heard the name Hank Nelson in February 1966, just forty-six years ago, at the Australian National University. I’d been appointed to the chair of history at the so far non-existent University of Papua and New Guinea, but I wasn’t moving until the beginning of 1967. I was asked to find someone to teach history to a group of between fifty and sixty students who were taking a year of preliminary studies that would prepare them for work towards a degree. Bill Gammage, a recent ANU graduate, readily agreed to go. But when he got to Moresby he found that somebody else was already there to take that very course, appointed by the principal of the PNG Administrative College, David Chenoweth, who in the scramble to get the university going had been given the task of organising the preliminary year. This somebody’s name was Hank Nelson. Some American blow-in? It turned out that he was a Melbourne graduate in education now lecturing at RMIT, and that Hank was the name conferred on him at high school. The confusion was happily resolved by Chenoweth and the newly appointed vice-chancellor, Dr John Gunther.

In mosquito-ridden tin sheds until lately occupied by a firm named Tutt Bryant, Hank and Bill teamed up to teach history to the young men and women – mostly men – aspiring to be their country’s first graduates. The Tutt Bryant School of Pacific Studies, Hank and Bill called the incipient university. Hank and Jan, who had met while teaching in Victoria, were married before they went north, and had three children by the time they left. I went up from time to time during 1966 for meetings of the professorial board in one of the sheds, and met some of the students at the Nelsons’ house.

Hank and Bill, boys from the bush, plain speakers, good listeners, encouragers, seemed to me wonderfully well suited to be mentors for these young people. I recall conversations at the Nelsons’ place with future leaders of the country, among them Tony Siaguru, Bernard Sakora, Bart Philemon and Rabbie Namaliu. (Bill reminds me that Charles Lepani was in the second-year intake of preliminary year students, in 1967.) And I remember Hank’s well-informed and shrewd briefing on PNG society and culture from the driving seat of a Volkswagen on a hairy journey up into the hills behind Moresby.

Bill came back to Canberra at the end of 1966. Hank, based for a while at the Administrative College and then in the sturdy concrete buildings of UPNG, taught in two courses on the history of PNG, one introductory and the other advanced. He also contributed to the Sydney-based fortnightly journal Nation on the rapidly changing politics of a nation poised for self-government. Penguin Books, spotting a likely author, commissioned from Hank what would become his first book, Papua New Guinea: Black Unity or Black Chaos (1972).

His lectures were always well-prepared, clear, and unerringly pitched, neither condescending to students nor overwhelming them. He responded to a high-tech lecture theatre, installed in 1969, with some amusement. “You feel bloody inadequate with just talk and chalk,” he said, tongue in cheek. In the advanced class he made much use of oral history, simply getting on with it while academics in Australia and elsewhere fussed about the rewards and hazards of the approach. Our external consultant, D.W.A. Baker of the ANU, judged this course the best of its kind he had come across.

Hank was a stickler for accuracy, in his own work and in the work of students and colleagues. After a lecture in which I had carelessly sketched the history of federal politics, he said with a smile, “Hey, you just abolished the Scullin government.”

Beyond the classroom he was a quietly sociable presence at sporting events and barbecues. He was a diligent boundary umpire at Aussie rules matches. He didn’t drink beer, though he was no wowser.

When I think of the special regard for Hank among students, this story comes to mind.

It’s 7.30 am, the time the UPNG day begins, and exams are on. Hank is supervising. As the examinees await permission to begin, one of them, Ekeroma Age, beckons to him and points to an empty desk. “Claire must be still asleep, Hank,” he says. “You’d better go and wake her up.” So the lecturer sprints off to the women’s dormitory and wakes Claire, just in time for her to get to the exam. This may be a story about the singularity of UPNG in those days, as well as about Hank.

In 1973 the Nelsons moved to Canberra, where Hank embarked on the thesis about gold mining which made him Dr Nelson and became in 1977 the book Black, White and Gold. As a PhD student he had been housed in the Research School of Social Sciences. Then he moved to the other side of the Coombs building to what in those days was called the Research School of Pacific Studies, and there he remained for the rest of his life. At the ANU he took to new fields of study – prisoners of the Japanese, bush schools, Australians in Bomber Command, all of them involving use of written and oral sources – while also pursuing subjects gestating from his PNG years.

In his advanced course in PNG history one common topic for oral history exercises had been “My Village During the War.” The second world war was now just far enough away for Papuans and New Guineans who had lived through it to talk candidly about their experiences, and close enough for their memories of it to be vivid. There’s a direct line from the testimonies gathered in that class to the award-winning film Angels of War, produced and directed by Hank, Gavan Daws and Andrew Pike in 1982. Hank’s other work out that year, Taim Bilong Masta, also draws on the collection of oral histories during Hank’s years in PNG, followed up in fertile collaboration with Tim Bowden to create the splendid series of ABC radio programs on which the book is based.

Hank has become legendary both for his own work and for his wise and self-effacing contribution to the work of others, young and old, whatever their place on a spectrum from empiricism to postmodernism. In recent years he has written for general readers masterly surveys of the intricacies of contemporary affairs in PNG and elsewhere in Melanesia.

Emeritus Professor Nelson, FASSA, AM. The well-deserved honours didn’t actually displease him, but he didn’t find it easy to take them with a straight face. He remained the boy from Boort, evoked in a lovely memoir recalling the days when he and his brother John drove to school in a jinker pulled reluctantly by a malevolent horse named Bunny.

I like to imagine him in a posture well remembered by John, in a paddock on the family farm, sitting on a tractor, reading a book. •

“What are you doing here?” | Bill Gammage

I WON’T be able to say all about Hank that he deserves. Few people achieve as much as he did, and fewer manage to keep their heads below the parapet so well. He was not one for public parade, but his influence was immense among the many students and staff he helped, or who heard his talks, read his books, heard him on radio, or saw his films. He established PNG history as a discipline, and entrenched into it an emphasis on the experience of Papua New Guineans. He wrote all his history about ordinary people.

I met him in Port Moresby early in March 1966, when he claimed that he was to help me teach the university’s first preliminary year history course. No one had told me that, but we soon settled on a course much better than the one I’d begun. I would continue with European history, where we had our only textbooks, and Hank would teach PNG history. This was a stupendous task. The few books available were on PNG’s colonial administration, but Hank was determined to talk about Papua New Guineans, so he set about searching the only records accessible: reports, statistics, regulations. From these he built up pictures of Papuan lives under the gavamani, comparing these with New Guinean lives in the taim bilong masta – plantation and goldfield labourers, carriers, boat crews, mission helpers, police. Soon Hank’s students were saying in class what their parents did in those days, comparing what should have happened with what did, and steadily bringing local knowledge and perspectives into their history.

The same careful, hard-working, commonsense approach that Hank showed in 1966 marked his work for the rest of his life. He was a born and committed teacher. His writing was simple and effective. Not for him any postmodernist navel gazing, and so he was among the few academics with a much bigger audience outside universities than within. He was a superb administrator, on the side of students, careful with budgets and reports, setting no-nonsense meeting agendas, never tempted into more than acting in those senior administrative jobs which convert most people from academics into lackeys for public servants.

One time we were on ABC radio, live to air, Hank and our host in Canberra, me in Adelaide. We had a yarn, then were asked what we thought of some aspect. Hank spoke, then our host said “Bill?” I said something like, “Yeah well, that’s what you’d expect Hank to say. He’s been on that line for years. You’d think he would’ve learnt a bit after all this time.” Hank said, “Bill’s a careful lad, but he used to play Rugby, which explains a lot. We need to be tolerant.” About when I regretted that Hank couldn’t run a chook raffle, our host concluded that we were drifting off course, and stopped us. Hank told me later that someone said to him, “I didn’t know you and Bill hated each other.” “Yes,” Hank said, “Sad isn’t it? And I have to work with him.”

That spirit never faded. In the hospice not long ago he asked me, “What are you doing here?” You might have to come from the country to appreciate that. Hank was a country lad. He grew up on a mallee farm near Boort, and he loved to talk about how the crops were, or the fallowing, or new varieties coming in, or the water debates. The bush shaped much of his writing: his MA on Port Phillip missionaries and Aborigines, his books on one-teacher schools, the country boys in Bomber Command or on the Kokoda Track or the Burma Railway.

In the 2008 Queen’s Birthday Honours Hank got an AM for outstanding service as a teacher and commentator on PNG. A tribute said in part:

Hank established PNG history as a discipline, from 1966 teaching it at the Administrative College and at UPNG. He co-wrote its first two texts for secondary and lower tertiary level (1968 and 1973), contributed regularly to Nation, and in 1972 wrote the first popular account of the emerging nation, Papua New Guinea: Black Unity or Black Chaos [though the title was not his and he did not like it]. He shifted the focus of PNG history from its administrators to its people – in a country of over 800 languages, with few published sources, no small achievement.

At ANU from 1973, Hank was the leading teacher, writer and commentator on PNG matters, and after hours, as he was scrupulous in observing, became an expert on Australians in the second world war. He published Black, White and Gold in 1977, With Its Hat About Its Ears in 1989, The War Diaries of Eddie Allan Stanton in 1996, and Chased by the Sun in 2002. He co-produced, co-directed and narrated the prize-winning film Angels of War in 1981, and helped make another prize-winner, Man Without Pigs, in 1989. For ABC radio he co-wrote and narrated Taim Bilong Masta in 1981 and Prisoners of War: Australians under Nippon in 1985, and wrote both companion books. He was historical consultant to numerous other documentaries on PNG or the Pacific war. Almost invariably his work revived a dormant public interest, most notably for former POWs. From the 1960s to 2011 his writing on contemporary PNG included regular contributions to Australian and Pacific media. Hardly a book, radio program, press comment or serious article on PNG was done without consulting him, and many students, public servants and Pacific islanders benefited from his teaching and wise guidance.

Hank was acting director of the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at ANU, a long-term convenor of Pacific and Asian History, and chair of Pacific History’s editorial board. In what is playfully called retirement, he chaired the council and the steering committee of the State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Program, or SSGM. He was elected a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in 1994, and made emeritus professor not long before his retirement in 2002. Hank made one comment on all this: “Haven’t you anything better to do with your time?”

Hank never stopped commenting. At two morning teas in his honour last year he was ill, and could easily have just got stuck into the cakes – he never stood back from anything sweet. Instead he gave two memorable talks. The first, at SSGM, began, “I trust there is no relationship between my gradual disengagement from SSGM and its obvious flourishing.” He gave statistics to prove that flourishing, then listed ways in which scholars might help PNG, under the headings Corruption, Compensation to Land Owners, PNG and Democracy, Governments by Competing Groups, and Autobiographies. His talk was a typically brilliant expression of practical concern for the wellbeing of the people of PNG. At the second morning tea he spoke almost entirely on how much he and everyone owed to the school and department secretaries and office staff. You see what sort of man Hank was.

It’s not easy to realise that a great mate is also a great man, especially when that mate was deceptively unobtrusive, unpretentious and egalitarian. But Hank was a great man. The 2008 tribute to him concluded:

Hank Nelson has been a pivotal and inspiring innovator, the pioneer of PNG history, an early exponent in bringing university work into the public arena via film and radio, a model in applying the highest research standards to illuminate experiences of Australians [and Papua New Guineans] in peace and war. Few academics parallel his range, diversity, and service, let alone to the people of two countries, Papua New Guinea and Australia. •