Why Acting Matters

By David Thomson | Yale University Press | $39.95

Anyone interested in film will be familiar with David Thomson’s indispensable Biographical Dictionary of Film, first published in 1975 and into its sixth edition by 2014. There are also book-length biographies of Nicole Kidman, Orson Welles and others, as well as more wide-ranging reflections on aspects of film and film-making. It is easy to disagree with Thomson’s assessments of any number of persons, films or ideas, for he is nothing if not idiosyncratic. But he is also provocative in the best sense of the term: that is, he provokes us into reconsidering long-held notions, and sometimes persuades us to drop these in favour of the line he has thrown out.

First, then, to the title of this new book. It sounds like a statement of intention but inevitably raises in the reader the corresponding question – why does acting matter? – to which we will then be looking for some kind of paraphrasable answer. I’m not sure we get one. Matters to whom? To audiences or to actors themselves? As diligent readers persist, they may well feel rewarded by the sharpness of unexpected insights while yet assaulted by a pretension that threatens to lead to disengagement.

Perhaps I’ve been too literal-minded in wanting Thomson to keep his eye on the theme his title seems to announce, but when he does, almost a third of the way into this slim volume, the effect is more than a little overwrought. “Finally, acting is nothing less than a description of the struggle between life and death, right and wrong, truth and dream.” Or, acting “can move thousands or millions of strangers in ways they will never understand.” But he can also surprise with the clarity of how media has made acting available for everyone: “We have been thrilled and amused, and we have taken actors and actresses into our private imaginary worlds.”

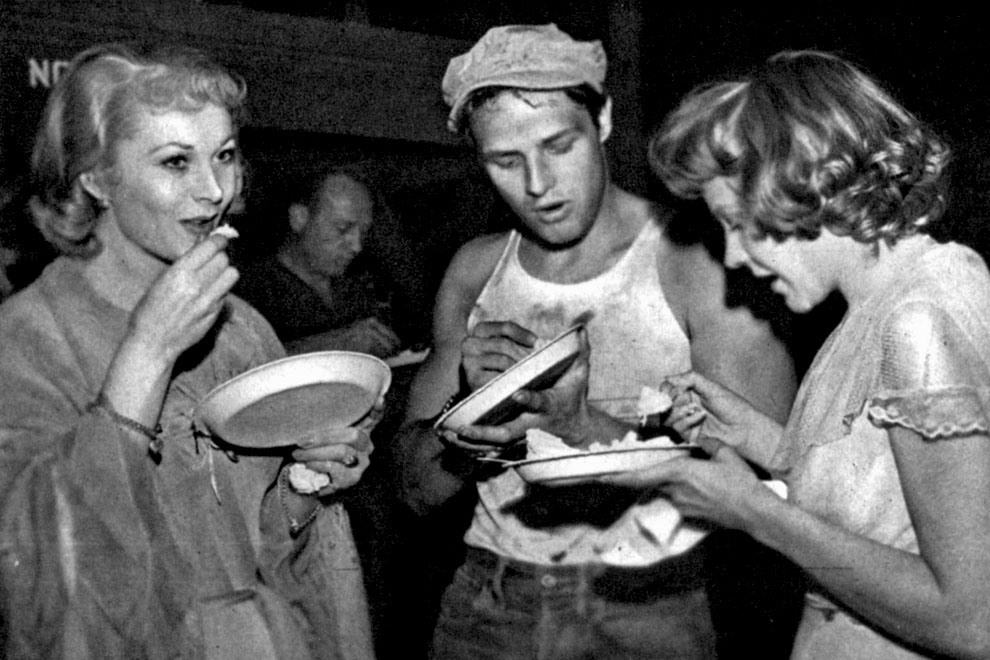

So, how does he go about dealing with the proposition announced in the title? One of the book’s strengths is its encyclopaedic overview of actors at work on stage or screen, in Britain and America, historic as well as the histrionic. He gives very vivid insights into the respective acting styles of, say, Marlon Brando and Laurence Olivier, always ready to move away from their spot-lit professional achievements to ponder the messier dramas of their personal lives – and equally ready to suggest connections between the two.

In fact, the inextricable meshing of the two is the subject of some of the book’s keenest aperçus: for instance, he considers the extent to which Vivien Leigh’s fragile emotional state was rendered more precarious in the course of her playing Blanche in the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire. This was directed by Elia Kazan, who had previously directed another English actress, Jessica Tandy, in the role on stage, where her performance drew attention to the “dangerous spontaneity” of Brando’s Stanley.

There are long and revealing accounts of Brando’s style as compared with Olivier’s, often evoking what made them so riveting in their respective countries and media. Thomson puts before us the spectacle of Olivier in The Entertainer, on both stage and screen, as the nudie-revue comic Archie Rice: “he was an arresting, insolent scoundrel, dishonesty made supreme. Those few feet away [on stage] I could see the greasepaint on his face and imagine the decay.” He is equally evocative in writing about Brando in, say, The Godfather, when the actor gave such a “convincing portrait of resolute age and the conflict between immigrant ambition and enforced wickedness in a man… aware that the actor needed to leave a hidden area, more secret than ingratiating or self-pitying.”

But though these two magisterially disparate achievements are made palpable before the reader – and the book offers many more such close-ups of what actors are up to in their diverse styles – I’m still not wholly persuaded that we are being shown why such acting matters. Nor does the perceptive analysis of how the advent of the movies affected the public’s relations with actors. The audiences for a theatrical performance may have run to thousands, but those for a successful film were more likely to be millions. As Thomson writes:

Before movies, leading actors were seen by only a fraction of the public. The screen ended that isolation, and it offered the actors in a way theatre had never possessed: it did them in close-up so that they were obliged to be better looking.

And the media – print, radio, television – were able to pursue them and present them, accurately or otherwise, to those who came to feel, by way of the screen, as if these performers were their intimates. For film stars, the studios’ publicity departments may have “colluded in a fraudulent bill of sale for an impossible intimacy… As in their films, so the publicity kept them adorable.” Celebrity on a scale scarcely imaginable by pre-cinema actors exacted its price from both actors and the watchers and readers who were so often given what they wanted to hear rather than what was actually the case.

The dark side of this fixation with celebrity is that quite often audiences become aware of what results from sudden extremes of wealth, and possibly from the pressure of public expectations, in matters of, say, scandalous divorces, wild extravagance, drug-taking and alcoholism. Thomson doesn’t avoid these by-products of the stardom with which audiences have rewarded actors. Perhaps this is another reason why acting “matters”: it may bring untold accolades to those who excel at it, but it can also exact untold costs from them.

Among the book’s sharpest perceptions comes in Thomson’s account of Olivier’s film of Henry V, when he recalls “the nervous actor preparing to be the king” before emerging as the magnetic eponym. This is a neat example of what he means when writing of the success of Shakespeare in Love fifty-odd years later, a success he attributes to “divining the show behind the show.” Actors, in the end, are people, adjusting their workaday selves to the wearing of diverse personas. And we empathise with this process because it is a more potent extension of the way we, in our everyday lives, present different selves to different people. Acting can help us to understand ourselves more comprehensively if we give it a chance. Actors’ scrutiny of themselves in the interests of a particular role may excite an element of self-scrutiny in more ordinary us.

One of Thomson’s devices is to invent imaginary scenarios about how actors’ lives and careers might have veered this way or that according to different roles they sought. In one vignette, an attractive young couple meet at the Bristol Old Vic, fall in love, marry, and are “available” for work: for him this might be in “a stupid Tom Cruise thing… a shit part but they think I’ll get noticed,” whereas for her it involves an audition, possibly requiring her to strip, for a role in “an experimental London production from Wedekind.” There are several of these mini-dramas, suggestive of the paths that may or may not be open and what may happen if they are taken.

I’m not sure the device tells us much about why acting matters, but it does give us some insight into the pressures of the profession. “To be an actor is to admit to the possibility of bipolarity: it is akin to being in work or not, having a role or a life, or waiting.” This is the kind of summarising comment the book offers: sometimes, it can seem deliberately oblique; sometimes, as here, tantalisingly to the point – and a point whose sharpness may not have struck us before. Acting can have its dangers, as in the case of Vivien Leigh, where life spills over into performance that then overflows back into the fragilities of life.

Even when I was puzzled as to exactly what Thomson had in mind by some of his more arcane usages, and even as I kept wanting and not quite getting answers to the issue implied in the title, there was never a time when my attention wavered. With Thomson, the reader is always on the look-out for the unexpected yoking together of idea and word and the light of insight that can follow. •