It is often said that when a film pitched in an area of major conflict draws disapproval and argument from both sides, they must be getting something right. What, on the other hand, can we conclude when both sides actually approve the representation of the struggle in question? This seems to be the case with Dror Moreh’s superb feature documentary The Gatekeepers, which presents the retrospective thinking of six former directors of the Israeli intelligence organisation Shin Bet. Its functions have been (and still are?) like those of ASIS and ASIO, the CIA and FBI combined; counter-terrorism, counter-espionage. The evidence from the six eloquent talking heads should set John le Carré fans off into an ecstatic spin: take these and these tracks into problem-solving, and you become part of the problem in no time flat.

As documentary, the film deploys a conventional range of tactics: the interviews, which take up most of the film’s time; archival film from many sources; and air-surveillance footage, with sights sliding and wobbling as a vehicle moves on an urban grid far below the helicopter, and then a fix on a suburban house, with fragmentary dialogue on the intercom: take them out or not? How much collateral damage? Still shots from the archive, and eloquent moving footage from the Six-Day War: never has that much-referenced chapter of recent history seemed so real. Footage of the Israeli leader Yitzhak Rabin moving round, deliberating and arguing, in the days before his assassination on 4 November 1995, letting us see that he wasn’t so saintly; and his busy presence in the huge, surging pro-peace rally in the moments before the event. Here, I’d have liked more on the mentality of the assassin, Yigal Amir, and the part played by religion in impelling his action (he’s still there, jailed for life).

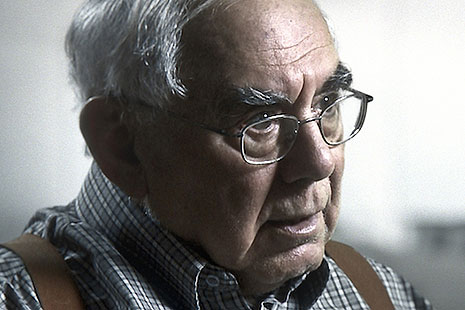

The assassination is the film’s pivotal moment; before it, The Gatekeepers takes in snapshots of the history, including the famous hesitant handshake on the White House lawn, with Yasser Arafat as the more willing of the two, and Bill Clinton (surely intent on his own role in the drama) standing back and between. These registrations of history provide the field in which each of the Shin Bet leaders speaks reminiscence and evidence, beginning with the first in sequence, Avraham Shalom. He’d be quite endearingly elderly, in check shirt and braces, if it weren’t for his unabashed ownership of Shin Bet’s tactics. One of the film’s chapter headings notes that it’s a story of tactics without strategy, a point reinforced by Shalom’s and his successors’ accounts; in supporting the settlements on the West Bank (and failing to comment on the overwhelming oppression of Gaza) they have a lot of trouble reaching the conclusion that – as I once heard a Jewish Australian mildly concede – “yes, the Palestinians do have a case.”

The other, younger witnesses are somewhat more ready to recognise the claims of the dispossessed; and speaking out as they do from privileged positions in the Israeli political establishment, they offer hope against hope. Shalom sees the future as dark; if there’s any light it can be glimpsed in the manifest honesty of the last speaker in the sequence, Ami Ayalon. With his lean, troubled face, he emerges as the most searching of all these highly intelligent operatives; as a presence, he could have been cast by Ingmar Bergman. Moreh gives him the last devastating line: “We’ve won all the battles, but lost the war.”

That clear assessment is the framework for the film’s making, and its circulation. Across the Western world, the recognition of the rights of the Palestinians and the extent of their oppression has been gathering force through the past decade. Thus the film’s appearance assumes a degree of receptivity in the audience; but when it comes to the Australian audience, a question floats around, as it were in the air in the cinema; how many understand what’s happening here? How many see and feel how startling it is that a film thus allows Israel’s agents to answer for their own record? The audience can only do so if they know Middle Eastern history, at least in outline, for the time since 1948. There have been many films; we can retrieve, among others, Paradise Now (2006), Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008); then this year’s The Other Son and The Attack, seen at the film festivals. All these filmmakers get beyond the obvious terms of conflict (and there’s one book I know that lengthens the view invaluably, Ilan Pappe’s History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples). The struggles in this arena are everybody’s business, not least when we too belong to settler societies; and more than ever in this particular moment here, when one unmerciful government is followed by another which seeks to apply always colder and harder forms of examination, exclusion and surveillance to the strangers within the gates.

YOU may have experienced the delights of the much-awarded The Rocket at the film festivals; they are worth revisiting now that this modest local film is on the circuits, not least its evidence of anthropology transformed as cinema. Entirely suitable for children from nine or ten upwards, it carries political freight, legibly but lightly; when governments and rulers, of whatever political stripe, determine on major construction projects, and small sustainable villages are swept away, who really benefits? A boy of ten, Ahlo, contemplates a giant dam, from the base of its wall and then from the walkway above. He goes swimming, and finds drowned statuary, pieces of a lost culture. A second dam will be built; Ahlo, his family and their neighbours will be dragooned away, and chivvied from one campground to another in the mountains of northern Laos. The filming of the settings, the forests and pathways, the beautiful open timber structures which are not quite houses, has both conviction and poetry; these places are well and truly known, and we can therefore be taken a long way into them.

The producer and director team, Sylvia Wilczynski and Kim Mordaunt, were there earlier for their documentary Bomb Harvest (2006); some of that film’s political elements are registered here, when we see that these forests are still littered with lethal ordnance. The story of a lone boy’s high aspiration is a very old one, but here it is stronger because Ahlo’s ambition, and a good deal of his screen time, are shared with his sane and determined little girlfriend Kia; both are motherless, but they have attending angels in Ahlo’s father Toma and Uncle Purple, who is something like a magician. The two kids are wonderfully played by Sitthipon Disamoe and Loungnmal Kaisano – and for them, the film leaves a trail of questions: what next for them? will other films be made in Laos? They should be; these filmmakers have opened a trail into a landlocked, poverty-stricken country which could well be better known. If The Rocket is something of a fairy-tale, there’s documentary bedrock underneath it. •