“YOU DON’T win because you don’t care enough.” The Ukrainian chess player’s pithy observation in Allan Massie’s fine novel A Question of Loyalties resonates today where the continent’s extremes meet, from the eastern borderlands to the far northwest.

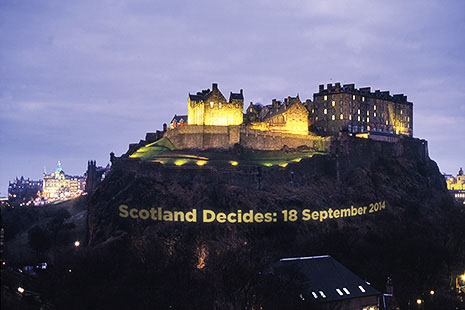

The violent political coercion in Ukraine is in deep contrast to the peaceful, democratic nature of the process under way in Scotland, where Scots will vote on their country’s independence on 18 September and therefore decide also the destiny of the United Kingdom state. Yet if the principles at stake in each case – sovereignty, law, citizenship, belonging – are similar, so too is the fact that those seeking to change the status quo seem driven by a far greater inner conviction than their adversaries. (And this is true of both their immediate adversaries and, in Brussels and London, their more remote ones.)

Scotland’s chief twentieth-century poet and controversialist Hugh MacDiarmid (1892–1978) is more often quoted by scandalised anti-nationalists these days, but his lines, “The present’s theirs, but a’ the past and future’s oors,” well conveys the confident ownership of the independence argument by the “yes” side, led by the Scottish National Party, or SNP, government in Edinburgh.

Greatly aided by an ultra-committed grassroots campaign (whose architect, Stephen Noon, describes its mantra as “conversion through conversation”), the “yes” side is managing an extraordinary feat. It is making “no” advocates resemble squatters in their own land, unable to offer a coherent vision of Scotland’s future as a nation in its own right. The latter are aware of the danger; as Alistair Carmichael, the Scottish secretary in London’s coalition government (and a Liberal Democrat), writes in the Scotsman on 16 May, “[in] this crucial debate on the future of our nation, we cannot allow the feeling to grow that to be on the other side of the argument from the SNP is somehow to be less Scottish.”

True, nothing is predestined in post-Calvinist Scotland. And a feature of this long campaign – launched in the early weeks of 2012 and thus now well into its third year – is that the anti-independence, or unionist, side has enjoyed a consistent, if lately diminishing, polling lead. It remains the favourite to win. But atmosphere and momentum matter, both in themselves and because they reflect what both camps perceive to be happening on the ground. With the winning post lying just beyond a packed season of symbolic national jousts – the Bannockburn battle anniversary, its Armed Forces Day rival, the Commonwealth Games, the Great War commemoration – the youthful Yes Scotland steed looks more sprightly than the Better Together pantomime horse.

THE EARLY weeks of 2014 made the contrast more marked, in two ways.

First, they provided fresh and vivid examples of the political misjudgement that has long gripped the wider case for unionism in Scotland. A series of speeches by the UK establishment’s economic A-team – prime minister David Cameron, chancellor George Osborne, Bank of England governor Mark Carney – questioned the case made in the Scottish government’s vast independence prospectus: namely, that a post-UK Scotland could expect to continue in a currency union with the rUK (“residual” or “rest of” the UK). The tone of the interventions varied according to the persona and his position. Cameron’s more placatory address (delivered at the site of the London Olympics) was a don’t-forget-Emeli-Sandé celebration of the United Kingdom’s “intricate tapestry,” Carney’s a nuanced outline of the concessions of sovereignty that a currency union would require (using the eurozone’s troubles as a subtle code). Osborne alone, the cold strategist to Cameron’s sunny-side-up act, exuded genuine menace.

Such warnings were reinforced by statements from several high-profile companies with head offices or extensive interests in Scotland. For them, the prospect of independence raised potential risks and costs that in principle might influence investment or location decisions. The Confederation of British Industry, or CBI, attempted to register as a “no” supporter with the electoral commission that governs the referendum process; this would allow it to spend money on advertising its views. In addition, UK ministers from several government departments continued to insist or imply that matters in their field of competence – defence and its contracts, pensions and their guarantees, energy and its subsidies, security and its intelligence sharing, the European Union and its conditions of membership – would turn out badly for Scotland if the country voted “yes.”

Taken together – especially by a Scottish public acutely sensitised to real or perceived slights from a southerly direction, but even by the non-aligned or mildly independence-sceptic – the heavyweight barrage looked and sounded intimidatory. An argument could be had on equal terms, was the dominant feeling; if the empire was striking back, though – whether consciously or because it couldn’t help itself – then it would be rebutted. The Scots, amid the flurry, realised that the political terms of trade between themselves and London had moved, if not actually reversed.

Indeed, the impact on the polls was the opposite of what London’s schedulers intended, for the ensuing weeks saw a perceptible rise in “yes” responses – albeit by different measures and without clarifying voters’ many underlying uncertainties. Moreover, fourteen leading Scottish institutions, among them universities and broadcasters, resigned from the CBI in protest at its implied political stance. And in a stirring editorial, Glasgow’s Sunday Herald – whose weekday stablemate is considered, alongside Edinburgh’s Scotsman, Scotland’s only national broadsheet – “came out” for independence (the phrase from the doomed Jacobite rising of 1745 seems oddly, perhaps ominously, apposite):

We believe that now is the time to roll up our sleeves and put our backs into creating the kind of society in which all Scots have a stake. Independence, this newspaper asserts, will put us in charge of our destiny. That being the case, Scots will have no one to blame for their failings, no one to condemn for perceived wrongs. We will, for the first time in three centuries, be responsible for our decisions, for better or worse… What is offered is the chance to alter course, to travel roads less taken, to define a destiny… The prize is a better country. It is, truly, as simple as that.

It’s too early to say that the first months of 2014 will prove a turning-point in the entire campaign (a case Iain Macwhirter, the Herald’s political columnist, argues with characteristic verve). These developments do, though, signal the exhaustion of the rhetoric of command as a tool of intra-British statecraft. The Scots, albeit helped by an ingenious filtering of the top-dog aspects of their past, have gone way beyond that. But all is fair in love, war and Scottish politics. The crucial question now is whether Better Together has anything more convincing in its locker.

HERE IS the second, and deeper, deficit in the unionist stance exposed in 2014: precisely the lack of a positive, driving – perhaps, above all, panoptic – argument for the UK union. This flaw has become ever more disfiguring since the establishment of the “devolved” Scottish parliament in Edinburgh in 1999 created new institutional forms of national community that pro-independence forces could in principle seek to exploit to lever more power. The election of a minority SNP government in 2007, and its re-election with a substantial majority in 2011 made these fears, and hopes, all the more acute.

The SNP, skilfully led by the take-on-all-comers first minister Alex Salmond, has been able to use the “devolution settlement” to position itself as the party best able to carry Scotland’s interests forward. Along the way, it has harnessed power, history, the sense of a national journey and a substantial cohort of the country’s intellectuals. Unionists, by contrast, have floundered.

Many factors have contributed. The withering of the structural bonds underpinning “Britishness,” from empire and religion to industry and welfarism, is a formidable obstacle to a revived unionism. Divided and dependent leadership matters too (with the unionist case split between three main parties – Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat – each inhibited by an often awkward association with its London HQ). Labour particularly has suffered from the indifferent quality of its senior team, with the party’s male heavy-hitters since 1999 favouring Westminster over Holyrood as their ladder of ambition. (This has left several impressive Labour women members of the Scottish parliament, or MSPs, to be gradually sidelined there.)

Every one of these is accentuated by a newer element: a dysfunction between unionism’s “Scottish” and “British” strands. In historical terms, support for a Scottish parliament with legislative powers has been seen by all British parties and their Scottish sections as quite compatible with – even a natural extension of – a strong London-centred UK polity. The colour of their unionism may have differed – the Tories’ martial-imperial, the Liberals’ home rule–federal, Labour’s statist-developmental – but none felt a contradiction between Scottish and British patriotism, not least because the latter was capacious enough to accommodate most versions of the former.

All is changed, palpably if not yet utterly. A continuing self-governing impulse now exists in Scotland, both as a local expression of global trends and as a measure of alienation from the content and style of UK governments (Conservative in particular). This makes it more than ever necessary for any unionist argument in Scotland to be Scotland-centred, portrayed in Scottish terms, explicitly advancing Scottish concerns, and it frames the residual UK link in frankly what’s-in-it-for-us terms. If that requires the impulse to sound almost indistinguishable from nationalism, or just a prosaic descent from more elevated notions of heart-stirring partnership, so be it. It also means that, here and now, the most effective proponents of the unionist position will tend to be Scots in Scotland. The finest words from any respected Westminster figure, far less from an establishment historian such as Simon Schama, will not cut it. The facts of life – as the Tory warhorse Quintin Hogg once said of his own party – are now quasi-nationalist, and starting from there may be the only way to preserve the United Kingdom.

For most unionists this remains a step too far. But a skewed recognition of it may underlie an abrupt refocusing of Better Together’s efforts. Alistair Carmichael, for example, writes that the “dual identity” of Scottish and British “works for us, personally and politically,” and that the United Kingdom “has ‘Made in Scotland’ running through every single part of it.” Labour’s former prime minister Gordon Brown, whose graveyard socialism still carries weight among the “yes” side’s prime target voters, provided his own twist in a speech in Glasgow on 22 April that put secure pensions, jobs, health and stable finance at the centre of a contractarian union-from-within:

[The] real debate is between two Scottish visions of Scotland’s future – the nationalist one based on the breaking of all political links with the UK and our vision based on a strong Scottish parliament backed up by a system of pooling and sharing risks and resources across the UK.

AMID the “no” side’s daily palpitations, Brown and Carmichael sound as if they care enough. But the referendum campaign so far confirms what the last two decades in Scotland (and arguably the whole period since the mid 1960s) show. The will to self-rule retains sinuous energy, and it represents global shifts and democratic pressures as well as a burgeoning of nationalist sentiment per se. Together, these have made the ground of political calculation in places like Scotland more complex and asymmetrical. This doesn’t have to be fatal to unionism (which as an ideological currency has many strands to draw on), but – like that Ukrainian chess player – former knights have to adapt to becoming pawns.

Perhaps, as in his case, that will only happen after catastrophe. It is too late to elaborate a comprehensive plan for a confederal United Kingdom before the referendum, which is perhaps all that could stand between Scotland and secession in the longer term. There are plenty of ideas around, though nothing near a consensus, including over the knotty matter of devolution for England. The open question of the United Kingdom’s (or rUK’s) membership of the European Union further clouds the view. But if the unionist cause does go down to defeat on 18 September, the two years of hard negotiation that follow before a Scottish state is established will give plenty of opportunities for its adherents to emerge from the general reassembly in new and perhaps reinvigorated form.

Yet even after a “no” vote, all the main British parties promise to support further devolution to the Scottish parliament (notably power over taxation). That means constitutional change will remain on the agenda whatever the result, though here the precise numbers will greatly affect the post-referendum dynamics. Turnout, which was in the low sixties in the referendums of 1979 and 1997, could become a factor; so could the preferences of the newly enfranchised sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds, almost 100,000 (or 80 per cent) of whom have registered to vote. Scots abroad, and in the rest of Britain where 750,000 live, cannot vote, which has provoked a legal challenge as well as frequent harrumphing in the press.

With its many public meetings and associated creative projects, the ardent campaign has been to Scotland’s democratic credit, though the hate-filled tone of some online coverage is not. It is little consolation that the zealots, among whom bigoted nationalists are in the vanguard, will lose many more votes for their own side than they gain.

In the end, though, the outcome will be a true expression of the views of Scotland’s people as a whole, and accepted as such by all sides. The contrast with Ukraine, as Allan Massie himself points out, is telling, and reflects something of the nature of the state that Scots and their English and other neighbours have created. But democracy is about choice not self-congratulation. The question facing Scots – should Scotland be an independent country? – cuts deep. The answer will test their own loyalties to the limit. •