There is something maddeningly paradoxical about corruption in the Philippines. No country in the Asia–Pacific region, with the possible exception of China, is mounting such an intensive effort to combat corrupt behaviour, yet the underlying structural causes are untouched, and the problem seems as intractable as ever. Two living former presidents have been charged with corruption offences, but the problem extends right through the political system and range of government agencies.

In July 2013, media in the Philippines published a series of stories claiming that five senators and twenty-three members of the House of Representatives were involved in a fraud involving the diversion of ten billion pesos (US$220 million) in public funds over the previous ten years. They were accused of benefiting from the alleged embezzlement of billions of pesos from the Priority Development Assistance Fund, widely regarded as a pork-barrelling exercise, under which the government allocated 200 million pesos to each of the country’s twenty-four senators and seventy million pesos to each of 290 members of Congress. Intended for development projects, the funds were used by the political dynasties to buy votes. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled the fund illegal, but only after a newspaper exposed a scheme to funnel money to bogus NGOs, which would then give kickbacks to politicians.

High-level officials and public servants are particularly prone to corrupt practices, according to the US Department of State’s Investment Climate Statements 2013. While the judiciary is constitutionally independent of the executive and legislative branches, it is understaffed and subject to corruption. Bribery is widespread and corruption is especially rife in local government. The extensive forestry sector is riddled with rent-seeking and corrupt practices. The military has been implicated in a number of corruption scandals, with senior and retired military officials accused of siphoning military funds to personal accounts. A 2011 survey found that almost 50 per cent of the population believe the armed forces to be the most corrupt of government institutions.

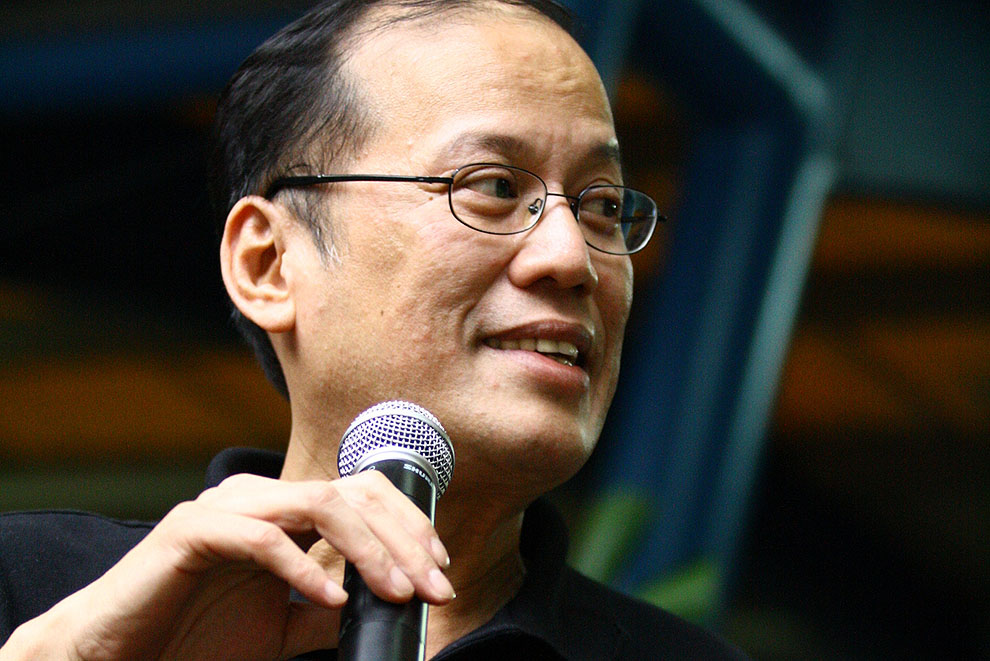

A culture of impunity, stemming in part from a case backlog in the judicial system, hampers efforts to clean up these parts of Philippine society. President Benigno Aquino’s laudable “straight road” campaign (matuwid na daan) continues to encounter heavy resistance in the legislature. Stalled in Congress are a number of key anti-corruption measures, including a freedom of information bill, fair competition legislation and a controversial anti–political dynasty bill that seeks to curb the influence of the powerful families who have held sway since colonial times. Whistleblowers are given no protection.

The real problem is power, and the powerful players in the Philippines, probably the most dynastic in the world apart from North Korea’s, are not only doggedly resistant to reform but baulk at even the mildest accountability measures. Despite the outward appearance of a presidential political system based on the US model, with a House of Representatives, a Senate and political pluralism, the reality is not so much a vibrant modern democracy as an essentially feudal state presided over by an enormously wealthy land-owning elite.

In itself, that isn’t unique. But on current projections, with a rapidly developing economy and a profound demographic shift under way, the Philippines is being propelled into a dynamically different future while it is still tied to an archaic social and political base that most of the former Spanish colonies cast off when they reformed land ownership in the nineteenth century. Without reform of the latter, the potential of the former remains severely constrained.

HSBC, the multinational banking conglomerate not noted for making extravagant forecasts, sees the Philippines leapfrogging from its current position as the forty-third largest economy in the world to be sixteenth by 2050. But without a modicum of transparency in the political system, the necessary confidence to fuel economic growth will stay on hold. The country’s power elite, the real source of a pervasive and seemingly endemic culture of corruption, simply refuses to yield.

The popular overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos in the 1980s might have removed a dictator, but the power structure remained largely intact – and for evidence one needs to look no further than the fact that his widow, the notorious Imelda Marcos, and his son, Ferdinand Jr, are both members of Congress today. Ferdinand Snr, according to official estimates, looted US$10 billion from public funds, of which only US$4 billion has been recovered. Only last year a former aide to Imelda Marcos was sentenced to prison for attempting to sell a US$32 million Claude Monet painting, part of the ill-gotten Marcos wealth.

Research by Ron Mendoza, executive director of the Asian Institute of Management Policy Center in Manila, starkly reveals how elected politicians in the Philippines operate as a self-serving oligarchy. Not only is the political elite strongly dynastic, with 75 per cent of all elected officials at national, sub-national and local levels having close relatives in similar positions, but – and this is truly staggering – the average net worth of a member of Congress is 178 times that of the average Filipino.

By way of comparison, in Thailand, the next country in the elected dynastic stakes, just 40 per cent of elected officials have close relatives in similar positions. The net worth of the average member of the US Congress is equal to the wealth of twenty-three typical American adults. Australia registers no dynastic significance and the gap between the net worth of elected members and ordinary voters is far lower, at around four times for a Labor MP or senator and sixteen times for a non-Labor representative.

Yet despite the ruling elite’s reluctance to open itself to greater scrutiny, fearless crusaders against corruption, both within government and outside it, are making some significant inroads.

The formidable national ombudsman, Conchita Carpio-Morales, who took over from the disgraced incumbent in 2011, told a conference last month that since she took up the position well over 6200 administrative and criminal cases have been resolved, 631 criminal complaints have been disposed and 825 cases have resulted in administrative penalties. By the end of 2014, she said, some 8700 cases were on the docket (a reduction of 12 per cent). She estimated that her agency would eliminate the backlog altogether by the end of her term in 2018. This is all the more impressive given the considerable backlog she inherited when she took over, including approximately 11,000 pending criminal and administrative cases.

One of the festering sores in the country is the notorious Bureau of Customs, but at the same conference the current commissioner, Bert Lina, spoke of reforms to enhance transparency and streamline customs processes, including improved monitoring of customs flows. Lina has been pushing for a paperless e-customs platform to facilitate data collection and dissemination, along with a performance management system to assess the efficiency of customs reforms. He has even invited civil society groups to partner with the bureau to develop scorecards and other analyses of its performance.

Civil society scrutiny of the Bureau of Customs has already had an impact, with activists photographing the expensive cars and lavish homes of lowly paid officials and using social media to pose the obvious questions. Just last week, two deputy commissioners resigned. But a prominent activist, Jesuit priest and Citizen-Customs Action Network head Bert Alejo, told me that much remains to be done.

Attempts at greater legislative scrutiny of the executive have been less successful. The powerful Senate Committee of Public Officers and Investigations has the job of investigating irregularities, but one senator, Aquilino Pimentel III, himself a former victim of electoral fraud, wearily told me how senators can stall the committee’s work simply by not making up a quorum.

The government’s efforts have not gone unnoticed ly. The country has gained eleven consecutive credit upgrades since the Aquino administration took over, and reached investment grade by late 2014. One key reason, says Ron Mendoza, is the improved governance climate, which has produced knock-on effects in macroeconomic stability, debt management and other economic indicators.

But President Aquino, himself a member of a powerful family and the son of a former president, comes to the end of his term next year, and just who will succeed him is far from clear, as is the future of his “straight road.” A bright future awaits the Philippines, but it could be delayed by an entrenched power elite steadfastly defending its feudal privileges. •