AS WE sped along the sandy track, bumping over ruts and slamming through axle-smashing gullies, I peered nervously out the window at a sun-bleached land speckled with scrawny goats, termite mounds and scrub. We were on our way to Dagahaley, one of five camps that make up the world’s largest refugee complex, in Dadaab, northeastern Kenya. Ahead of our car, a police truck with our obligatory escorts raised dust and lifted my anxiety level.

Were there any explosive devices under the sand? Would the shrapnel reach our car if the truck were hit? My natural pessimism was not unwarranted. Just a few days after my visit, a Kenyan Red Cross ambulance was attacked by gunmen on the same road. Kenyan police patrols have also been targeted inside the camps.

Shootings, bombings, rape and robbery are also real dangers for the 448,000 mainly Somali refugees living in Dadaab. Dadaab became a media hotspot in 2011 as thousands of Somalis arrived on foot, fleeing famine and the atrocities committed by al-Shabaab militants. For their part, the militants use the sprawling camps — which lie just ninety kilometres from the border with Somalia — as a safe haven. Pictures of emaciated women clutching sick children defined the world’s view of the camps at that time.

This violence is what the outside world associates with this part of the world — along with the hunger and death. But just as Los Angeles is home to both Hollywood and a lethal gang culture, and London encompasses the opulence of Knightsbridge and the gritty council estates of the East End, so Dadaab, one of Kenya’s largest urban centres, is more than the sum of news headlines.

People go to the market, study at school, wash their clothes, decorate their homes, dance, sing, rap, play basketball and joke — all away from the gaze of the world media. Now, the refugees themselves are telling these stories through a multimedia project that aims to create a three-dimensional picture of life in the camps. The stories are as unique as Dadaab itself — a vast refugee camp that has become a permanent home for generations of displaced Somalis.

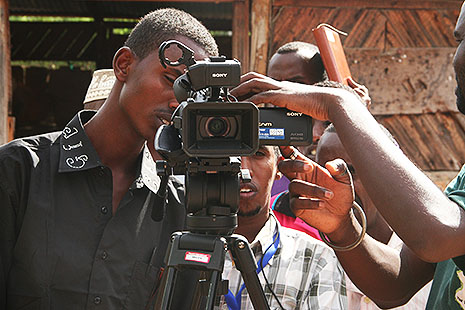

Dadaab Stories was created by FilmAid, a humanitarian organisation that has been working in Dadaab since 2006. The project brings together poetry, music, community journalism and personal blogs, as well as video interviews.

One video clip features Yusef, a twenty-five-year-old who runs the Dagahaley Body Fitness Centre, the only gym in Dadaab. As young men pump weights inside a small room walled with corrugated iron sheets, he encourages them by quietly repeating, “Strong, strong.”

Yusef, who arrived in Dadaab in 1992, talks about how his friends in the diaspora helped raise money to buy the basic equipment. “My dream is to become an actor,” he says. “That is why I am building my body. My future will be like that man,” he concludes, referring to Arnold Schwarzenegger. Then he adds, as if to soothe the viewer’s innate scepticism, “… if possible.”

Rafiq Copeland, one of the creators and executive producers of Dadaab Stories, tells me this is one of his favourite clips. “I could watch that over and over again,” says the Melbourne-born film-maker, who is humanitarian liaison officer for Internews Europe, a development organisation that works with journalists in the camps. “Here is someone who has started his own business. It’s the opposite of what you would imagine when you think of a refugee camp. It’s a really good story of someone doing something positive and defying expectations.”

People might also be surprised by a featured music video, “Dear Mr Peace,” performed by the Dadaab All Stars. “What we need is love, love, love. What we need is peace, peace, peace,” sing three ostentatiously cool young men, as sleek women in vest tops, and others in traditional buibuis, or shawls, dance in the background. The song mixes lyrics in French, Swahili and English. Some of the singers rap, some croon. It is a fitting metaphor for the diversity of a place that is all too often defined by a single thread of its complex narrative tapestry.

Liban Rashid, a twenty-five-year-old who worked as a field producer for Dadaab Stories, also tells his story in one of the videos. He came to the camps as a child but his father, a religious man and a farmer, returned to Somalia, where he was killed. Rashid hopes to join his family in Minnesota, where they have been resettled; in the meantime, he is putting his father’s advice “to depend on myself” into practice.

Dadaab Stories is “about giving a voice to the community and giving a clear picture of the situation in the camp, with both positive and negative stories,” he tells me. “There are so many talented youths in the camp, who know about music and singing, who are just here, and they think nobody needs their talent. Now, they can share their stories, and some people might like what they are doing, and might give them a market.”

The inhabitants of Dadaab challenge the very notion of what constitutes a refugee. The desperate people who arrived on foot from Somalia two years ago are part of the picture, but only one element. Around 8000 children in the camps have parents who were themselves born in the camps. Dadaab is the only home these people have ever known.

JUST as Dadaab’s residents defy the refugee stereotype, so the camps have their own distinct personalities. Dagahaley is one of the oldest camps, established when the complex was opened in 1991, and its winding streets lead to mud-plastered homes surrounded by fences made from kimora plants. It is also home to thriving businesses, hotels, schools and hospitals. Kenyatta University plans to open a campus here to cater to refugees and people from the host community. It will be the first higher-education institution to service a refugee site.

But since a spate of kidnappings in 2011 and 2012, access to the camps has become increasingly difficult. Two Spanish doctors with Médecins Sans Frontières were seized from Ifo 2, one of the newest and most insecure camps, in October 2011. They are still missing, believed to be in Somalia. Even aid agencies on the ground have limited access to the camps, which are administered by the UN refugee agency UNHCR. Foreign visitors must take a police escort.

In Dadaab Stories, the refugees’ voices are heard beyond the constraints of this insecurity, in a context not defined by need. The project demands only one thing from outsiders: curiosity, though it required a lot more from the refugees who worked on it.

Copeland tells me that some of the producers were questioned by nervous Kenyan police who feared those filming might be planning attacks. And there were fears the refugees who appear onscreen might be targeted by armed groups in the camps. “We worked closely with the protection officers, and we were very candid with anyone who is involved about the fact that it would be online,” Copeland says. “It was a concern and it still is, but we found ways of doing things. People want to get their stories out there.”

Friends warned Rashid that he might be shot for filming, but he was undeterred. “We have tried our best, and we will continue,” he says. “I will do what I can to spread our stories.” Most of the story ideas came from the refugees themselves, covering subjects including rap artists, an Ethiopian dance troupe, basketball players, a cholera prevention scheme, and a trip to the camel market.

One of the most touching videos features Mohamed Ali Ahmed, a former professional football player and father of nine children who is the sole caretaker for his severely disabled son, Abidirsack. “I love this child, and disability can strike anyone. I am determined to care for him until one of us dies,” Ahmed says. We see him washing his son, laughing with him and stroking his hair. He says the women of his neighbourhood take care of Abidirsack, who is thirteen now, when he needs to go to work.

Rashid, who has received many emails congratulating him on the project, believes stories like this will debunk stereotypes, while the project’s very existence may cause some to question their assumptions about refugees. “It’s a wonderful thing,” he says. “People never thought refugees could do and manage a thing like that.”

For Copeland, this is exactly the point. “There’s this helplessness that people associate with refugees,” he says. “They do need assistance but it doesn’t mean they don’t have agency over their own destiny.” •