FOR five days early this month, Kenya held its breath. After queuing for up to ten hours to choose their president, Kenyans endured an even longer and more agonising wait as the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission struggled to deliver results in the most complex and important election since independence in 1963.

At first, all went well. The numbers flowed in, and the electronic screens at the commission’s tallying centre in Nairobi updated reassuringly. But then the updates sputtered, slowed and finally stopped. The electronic system had crashed, the commission announced, and it was resorting to tallying the votes manually.

Information was sketchy, and allegations of rigging began to swirl. But these troubling questions took second place to the main concerns – who had won, would there be a second round, would peace prevail?

Finally, five days after the poll, Uhuru Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s first president Jomo Kenyatta and the country’s richest man, was declared the winner with 50.07 per cent of votes cast. That was scarcely 8000 votes more than the cut-off point that would have triggered a second round.

But still Kenya held its breath. How, we wondered, would the losers react, especially given their claims about serious anomalies? All eyes were on the losing candidate, prime minister Raila Odinga, not least because it was his defeat and allegations of fraud in the 2007 ballot that led to the explosion of brutally intimate, tribe-on-tribe violence that cost around 1200 lives and cast such a shadow over this election.

In a sun-dappled garden in one of Nairobi’s upscale neighbourhoods, Odinga, who got 43.31 per cent of the vote, finally appeared before the cameras. He refused to concede, but urged his supporters to remain calm, promising to challenge the results in the Supreme Court. A few tense hours after this appearance, Kenyans collectively began to breathe again. Peace appeared to be holding.

So what was different this time? The theories are manifold and the truth probably lies in a combination of factors, some obvious, some reflecting a more Machiavellian reading of those five tension-filled days.

Before the poll, many Kenyans spoke of lessons learned in 2007, arguing that people didn’t want to descend into the abyss of looting, burning, murdering and raping that brought east Africa’s largest economy to the brink just over five years ago. In the weeks before the 4 March vote, I spoke to peace activists, tea farmers, youth leaders and many others, all of them fervently hoping for peace.

Mercy Wanjiru, a twenty-nine-year-old actress who starred in a peace film called Ni Sisi (Swahili for It Is Us), said Kenyans had seen the cost of violence last time, and did not want to pay it again. “People really suffered,” she said, sitting in her tidy apartment beside a pile of toys belonging to her one-year-old daughter, Angel. “Houses were torched, people lost their relatives, their livelihoods…” Kenyans, she believes, are tired of all that. “They just want development, they don’t want setbacks, and now people are more enlightened.”

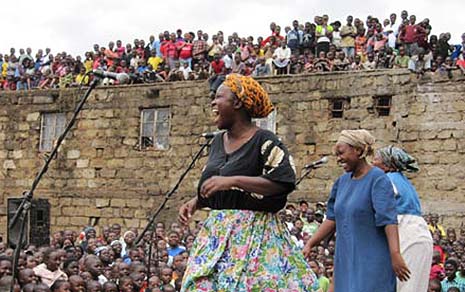

Wanjiru’s answer encapsulates many of the factors cited by analysts to explain the calm since the election – as does her profession. Activists like her, as well as celebrities, musicians, graffiti artists and religious leaders, worked hard in slums and villages across Kenya to spread a message of peace. The candidates too called for peace, with Kenyatta, a member of the dominant Kikuyu tribe, and Odinga, a Luo, appearing together at a prayer meeting in Nairobi a week before the vote.

Kenya’s press and broadcasters threw their weight behind the campaign – repeatedly urging people to stay calm during the marathon tallying process. There has been some criticism, however, that this pro-peace push took the edge off a media renowned for its combative spirit.

For Kenyatta, the result showed that Kenyans had “demonstrated a level of political maturity that surpassed expectations.” But not everyone agrees. “It was not… a renewed self-confidence that drove us,” Kenyan cartoonist Patrick Gathara wrote on his blog. “Quite the opposite. It was a fear, a terror, a recognition that we were not as mature as we were claiming to be; that underneath our veneer of civility lay an unspeakable horror just waiting to break out and devour our children.”

Fear may be one factor that led to the post-election silence from Odinga’s supporters. There was a heavy police presence in his strongholds, and no doubt the fear of personal loss, and vivid memories of the cost of dissent last time, played their part.

But if that is a negative reading, there are positives to take from an election that saw Kenyans choose senators, county governors and members of parliament, as well as a replacement for president Mwai Kibaki.

Veteran journalist Charles Onyango-Obbo pointed to economic development as a key factor in determining reaction to the results. “If you give people real hope that tomorrow will be better, and you build symbols to that hope, they are inclined to be less violent. Therefore a couple of projects and structural shifts explain why Kenya had a peaceful election,” he wrote in Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper. He mentioned the Thika Superhighway that leads out of Nairobi, and the upgrading of the airport in Kisumu, a western town on the shores of Lake Victoria in Odinga’s heartland.

Another potent factor was a renewed faith in the reformed judiciary, now led by chief justice Willy Mutunga, a widely respected former rights activist who received death threats before the vote but feistily responded that the justice system would not be held hostage by a “cabal of retrogrades.”

THIS election has exposed a country on the cusp, struggling to fulfil its economic potential, propelled by institutional reforms like the 2010 constitution and devolution but fettered by an ethnic-based politics exploited by a canny elite brought up to divide and rule. Once again, assuming the results are broadly accurate, Kenyans seemed to vote on ethnic lines. Alongside those loyalties, the rise of a kind of jingoistic patriotism harked back to the past rather than anticipating a confident future for a country that drives growth in its region, boasts an innovative IT sector, and has ambitious plans to become a middle-income economy.

Kenyatta, who may face trial at the International Criminal Court, or ICC, this year for crimes against humanity related to his alleged role in orchestrating the violence in 2007–08, chose William Ruto, a Kalenjin who is also facing trial at the ICC, as his running mate. Both men deny the ICC charges. Together, aided in no small measure by the ICC’s apparent inability to push the cases forward, they helped turn the election into a referendum on Kenyan sovereignty. The portrayal of the ICC as a Western construct, intent on harassing African leaders, has resonated across the continent.

It did not seem to bother Kenyatta’s supporters that he and Ruto, a former ally of Odinga’s, were fierce enemies in 2007, and that some of the most vicious attacks involved their two communities. An optimistic reading would say voters believed that giving power to these men would preserve peace between the Kikuyu and Kalenjin. But analysts say the alliance is fragile, with no guarantee it will hold under the strains of government.

The ICC charges also mean that Kenyatta’s yet-to-be-confirmed victory may prove a headache for foreign diplomats, but his indictment is looking increasingly shaky after a key witness withdrew.

While Kenyans wait for the result of Odinga’s legal challenge, and an ICC ruling on whether the case against Kenyatta can go ahead, life has returned to normal: people have gone back to work, schools are open and Nairobi’s infamous traffic is clogging the city’s arteries again. And yet there is still a sense of caution.

On Saturday, Odinga’s team filed their legal challenge against what the prime minister called “stunning IEBC failures” that led the once-lauded body to conduct the poll in a “criminally negligent” manner. “I have no hesitation whatsoever in lawfully challenging the election outcome,” he said. “To do otherwise would be a betrayal of the new constitution and therefore of everything that Kenyans hold dear. They would forever lose their faith in elections and democracy.”

It is hard to see how the Supreme Court can dismiss out of hand all the allegations of incompetence, inflated voter registers, and improper tallying. On these points, Odinga’s dossier appears comprehensive. But if the judges do reject the claims, how will Odinga’s supporters react? Will the hunger for peace prevail over fury at another perceived ballot-box robbery?

It’s a heavy burden for Chief Justice Mutunga. After receiving the death threats in February, he said he was ready to lay down his life for justice and democracy. But is he willing to risk the lives of others? If the court finds in favour of Odinga, will he order a second round, knowing that could stoke the flames that nearly consumed Kenya five years ago? •