The Holtermann Collection

State Library of New South Wales

In 1951, in a backyard shed in the Sydney suburb of Chatswood, the photographer, journalist and photographic historian Keast Burke found what he had been looking for: a collection of glass-plate photographic negatives, some 3500 in all, neatly arranged in boxes made of cedar or japanned tin. The photographs had been taken in the 1870s by the splendidly named Beaufoy Merlin and his assistant (and ultimate successor) Charles Bayliss, working under the patronage of the larger-than-life visionary Bernhardt Holtermann. Burke’s excitement comes through clearly in an account he wrote for the Australasian Photo Review in 1953, in which he drew a parallel between the recovery of the Holtermann archive and the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb thirty years before. For Burke, this was an archaeological treasure that comfortably held its own against the riches of Ancient Egypt.

Here were photographs that recorded a “life and culture” – most notably the life and culture of the goldfields of Hill End and Gulgong in western New South Wales – that had become part of the remote past, a kind of ancient civilisation. Here, wrote Burke, “were incredible numbers of negatives, records that were in due course to disclose every detail of the lives of our goldfields pioneers – the men, the women and the children, their homes, their business enterprises, and their mining shafts, their populous towns and larger cities.” In 2013, sixty years after Burke first entered that Egyptian tomb, photographs from the trove, newly and painstakingly brought to life from the glass-plate negatives using high-end digital scanning techniques, form the core of the State Library’s restored collection.

From the beginning, even before Bernhardt Holtermann came on the scene as patron and financial supporter, the photographs were intended to be a comprehensive record – of Australia, of a new landscape and of a new way of life. The primary motivation was, of course, commercial. Merlin, having tried his hand as an actor and a theatrical entrepreneur, had latched onto the new art of photography in the 1860s and, assisted as the business grew by the youthful Bayliss, established the American and Australasian Photographic Company. (In addition to adding an alliterative touch, the “American” appears to have served the same purpose as “international” or “global” would today, implying a broad sphere of activity and a worldly clientele.) Under this banner the two men travelled throughout southeastern Australia, lugging their cumbersome equipment and photographing people and places as they went.

Stealing a march on Google Street View by a century and a half, Merlin had the brainwave of documenting the streetscapes and individual buildings of Melbourne and the country towns of Victoria, and later of New South Wales, building up a portfolio of images that could, for a fee, provide would-be settlers and investors with an idea of what they could otherwise only imagine. “You could go into their studio in Sydney,” says the State Library of NSW’s Alan Davies, “pay a shilling, and look at their photographic library of Goulburn.” For the people who had no need to imagine Goulburn because they were already there – or in one of the many other towns that the photographers visited – these images, generally produced in the small, carte de visite format, were a record of the lives they had made and the buildings they had built, the success they had found or, standing upright for their portraits in their best Sunday suits or borrowed outfits, the success they hoped to find.

While Merlin and Bayliss were travelling and taking pictures, Bernhardt Holtermann, a young emigrant from Prussia, struck it lucky on the goldfields of Hill End and made his fortune almost overnight. A man with an eye to posterity, he began to think of ways to celebrate the country that had made him rich, and to encourage others to follow his example by leaving the old world for the new. It just so happened that Beaufoy Merlin was in town, plying his trade to the goldminers and shopkeepers of Hill End, Gulgong and surrounding areas, and so one of the great patron–artist relationships in Australian history was born, between a man who instinctively understood the power and potential of the new medium, and a man who understood exactly how it worked.

What became known as the Holtermann collection was intended at least partly for an international audience. Photographs taken by Merlin and Bayliss, at the behest and often the specific direction of Holtermann, were exhibited to considerable acclaim at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876 and the Paris Exposition Universelle Internationale in 1878. For all his focus on the future, it seems clear that Holtermann was also aware that the rapid changes he was part of – and that his project was so comprehensively documenting – were rapidly becoming part of the past.

Not only would many of the people captured in the photographs die early from accidents and illness and lack of available or competent medical care (indeed, Merlin, Bayliss and Holtermann were themselves all destined to die in their forties) but also the streetscapes and urban panoramas that formed a substantial part of the collection would very soon be historical documents. In the case of Hill End, the buildings that went up quickly to service the new gold town went down again almost as quickly, after the rush was over and the caravan had moved on.

Despite the rapid pace of change, what strikes a viewer now is the quality of stillness in the photographs, the way time seems to have stopped to allow the images to be captured with such sharpness. The deliberate and posed nature of early photographs can be unsettling, not least because we have gotten out of the way of stillness and have become used to the kind of photography, whether of wars or weddings or the natural world, that puts us into the middle of the action and invites us to continue animating it in our minds. The capacity of modern digital photography to record the instant has meant more and more photographs of more and more instants, sometimes staged, sometimes drawn from nature.

Add to this the popularity in recent years of such innovations as the cinemagraph, in which a portion of an otherwise static image can be made to move continuously (hair blowing in the breeze, champagne bubbling); or the one-second video (contestants in the Montblanc Beauty of a Second competition of 2010–11, which ran under the oversight of film director Wim Wenders, were invited to “seize the moment”); or the up-to-six-seconds format of the recently launched Vine, a visual companion to Twitter “that lets you capture and share short looping videos.” This blurring of the distinction between still and moving pictures seems like a logical extension of our expectation that the photograph should convey a sense of movement, a sense that everything is going unstoppably forward.

The formal pose has come to seem artificial, or a deliberate aesthetic choice on the part of the photographer, rather than being dictated by the limitations of the medium. At the most basic level, there is no longer any need for the sitter to sit still. Keast Burke admired Merlin for his ability to capture his subjects with “little sense of strain” in their bearing or expressions, despite the requirement for them “to ‘hold it’ for five or ten seconds.” (Burke put this down to Merlin’s habit of being “always gentle, persuasive, artistic and confident.”) To achieve that level of composed stillness today, to recapture something of the insight of the traditional studio portrait by exploiting or perhaps bypassing the self-consciousness of the modern, media-savvy sitter, calls for increasing inventiveness on the part of the photographer. Indeed, some of the best contemporary photography does just that, reworking the portrait and reinventing stillness – by echoing older practices of dressing the subjects in costumes or arranging them in tableaux, for instance, or by catching the subject unawares, as in Tim Hetherington’s Afghan war photographs of sleeping soldiers.

IN HILL END, in the early 1870s, this quality of stillness was inherent in the very business of producing a photograph. These photographs were made rather than taken, by means of a long process that stretched from the coating of the glass plate, itself a delicate and laborious business that was not always successful, to the development in sunlight of the final image. It was taxing work, requiring enormous skill and patience on the part of the photographer. In one such composition, a wedding portrait (below) of the seventy-one-year-old Dr John O’Connell, medical officer at Hill End Hospital, and his twenty-four-year-old bride Theresa, née Cummins, the figures seem pasted onto the background, unconvincingly linked to one another by means of the bride’s hand resting lightly on the groom’s shoulder, their pose of intimacy and physical connection telling us that this portrait shows not a father and daughter, as a first glance might suggest, but a couple about to embark on married life.

Dr John O’Connell, medical officer, and his twenty-four-year-old bride Theresa, née Cummins, at Hill End. State Library of New South Wales

Because blue or very light-coloured eyes did not reproduce well in photographs of the day, Theresa has something of a blank, almost frightened and otherworldly look, in contrast to her husband, whose darker eyes and fixed stare suggest self-confidence and purpose. That impression is almost certainly false: the library’s label quotes an item in the Hill End Observer lamenting O’Connell’s professional shortcomings, including the “lack of ‘a firm, steady hand.’”

While the doctor appears nailed to the floor, Theresa’s otherworldliness is compounded by the fact that she seems on the point of floating upwards to the ceiling – an effect that probably derives, ironically enough, from the lack of a ceiling to float up to. The absence of a roof meant that natural light, all-important to the making of a photograph, could stream in unimpeded. In what was in effect a pop-up studio, there may even have been reflectors in use, or some kind of device that allowed the intensity of the light to be managed according to whether the day was sunny or overcast. The result is an almost over-illumination from above of Theresa’s face and a corresponding darkening of the area below the hem of her dress, producing the impression that, rather than holding onto her husband, she is about to let go. Theresa was to die seven years later, at the age of thirty-one, following a stillbirth.

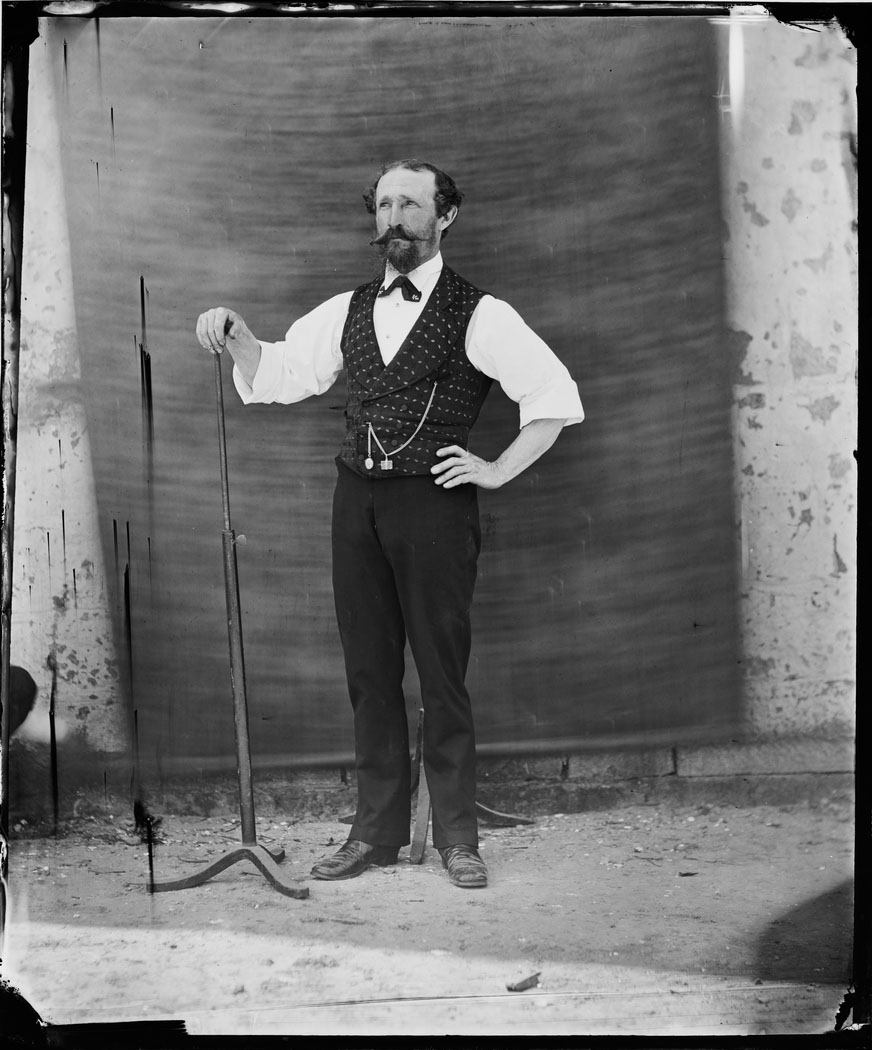

So important was it for the subjects of the photographs to remain still for the duration of the exposure that they were literally clamped to the spot, by means of an instrument that resembled a hatstand. The device can be seen most clearly in a portrait of Bernhardt Holtermann (below) from 1875, in which he stands proudly beside the height-adjustable device, his hand gripping and thus obscuring the small padded wings that fitted to the back of the subject’s head to hold it firmly in place. A second set of metal feet is visible behind him, presumably part of the contraption holding up the background screen but also, it is tempting to think, helping to hold up Holtermann. The photograph was part of a dummy run for several montage images of Holtermann standing, with proprietorial air, next to the so-called Holtermann Nugget. The actual nugget had long since been crushed and dispersed but not before it had been photographed for posterity shortly after its discovery by employees of Holtermann’s mine.

The wealthy, larger-than-life visionary Bernhardt Holtermann, who funded much of the two photographers’ work. State Library of New South Wales

By substituting the nugget for the head-clamp and adding a more impressive background – the veranda of Holtermann’s North Sydney mansion, built with the proceeds of his success on the goldfields – Holtermann’s permanent association with the nugget was assured. But in the context of the making of the entire collection, it is not so much this proto-Photoshopped image of Holtermann and his nugget that commands our attention, as the original template of Holtermann and the “hatstand,” which serves as a reminder of the effort – on the part of both photographer and sitter – that went into these photographs.

Nowhere else in the collection do we see the head-clamp so clearly and entirely, but there are occasional hints and glimpses. Sometimes the device is covered by drapery; more often it can be inferred as lurking behind a false skirting board. A gap between the board and the wall served to accommodate the feet of the device; sometimes this gap is made visible by the angle at which the subject – the diminutive Miss Jeffree, for example – is viewed by the camera. And sometimes, as in the portrait of the young August Godolf on his top-of-the-range tricycle, or that of On Gay, a snappily dressed Hill End shopkeeper – shown with one hand holding an umbrella, thus affording himself additional stability – the trunk of the clamping device can just be seen, not quite hidden by the human subject in front of it.

Children, then as now, found it particularly difficult to keep still, whether clamped or unclamped, to the extent that many studios of the time charged double for photographing anyone under the age of four. For parents, the price was worth paying, not least because the resulting photograph acted as a kind of hedge against the real possibility that their child would not survive into adulthood. The State Library exhibition that launched the restored photos included a greatly enlarged digital image of the children of Hill End School, taken in 1873, the year after the school was built; the resolution of the photograph is so fine that it is possible to zero in on the faces of individual children, separating them from their fellows and singling them out from the crowd, leading us to wonder what became of them, and whether they survived into adulthood.

All 3500 images from the Holtermann collection can be viewed online. Many are of buildings or open country rather than people, but a surprising number combine human figures with views of the built and the natural environments, something of an innovation by Merlin. People are photographed outside their homes or shops or pubs, or pausing in the middle of the street; in the latter case, when there was nothing handy for the townspeople to lean on, it was harder to keep still and the faces as a result are often blurred. The facades of buildings, on the other hand, could serve as a kind of outdoor head-clamp, as shopkeepers and customers leant for support against the structures behind them. In the Hill End and Gulgong photographs in particular, the people and the buildings seem almost to be propping each other up.

AFTER Beaufoy Merlin died, in 1873, Bayliss stepped naturally into the role of lead photographer. With Holtermann’s encouragement, he became even more adventurous technically, producing large and sometimes gigantic glass plates of up to a metre by a metre-and-a-half, the largest ever made. The urban and harbourside panoramas of Sydney and other places that Bayliss, often actively assisted by Holtermann, captured with these super-sized plates still have the power to thrill today, with their comprehensiveness of detail and their extraordinary level of resolution, impressive even by the standards of twenty-first-century digital imaging technology. The collection itself, including these startling panoramas, nevertheless represents a mere fraction of the images that were made by Merlin and Bayliss. The vast majority have disappeared, and it is highly unlikely that there are any more garden sheds.

But the images that have survived make up a remarkable resource, for historians not only of photography but also of economics, agronomy, architecture, manners, costume and food, as well as, more generally, for anyone interested in Australia’s past. For that we should thank Holtermann, as the enthusiast and visionary and provider of crucial funds; Bayliss, who progressed from a sixteen-year-old apprentice to Beaufoy Merlin to an outstanding photographer in his own right; and most of all Merlin himself, who was the one who started it all. He died before the jumbo plates and the panoramas brought international attention to the enterprise, but the entire project grew out of his talents as an entrepreneurial, an artistic and a technical wizard. It is no wonder that after toying early on in his career with various spellings of his name – Murlin, Merling, Muriel – he settled on Merlin as the one that seemed the best fit. •