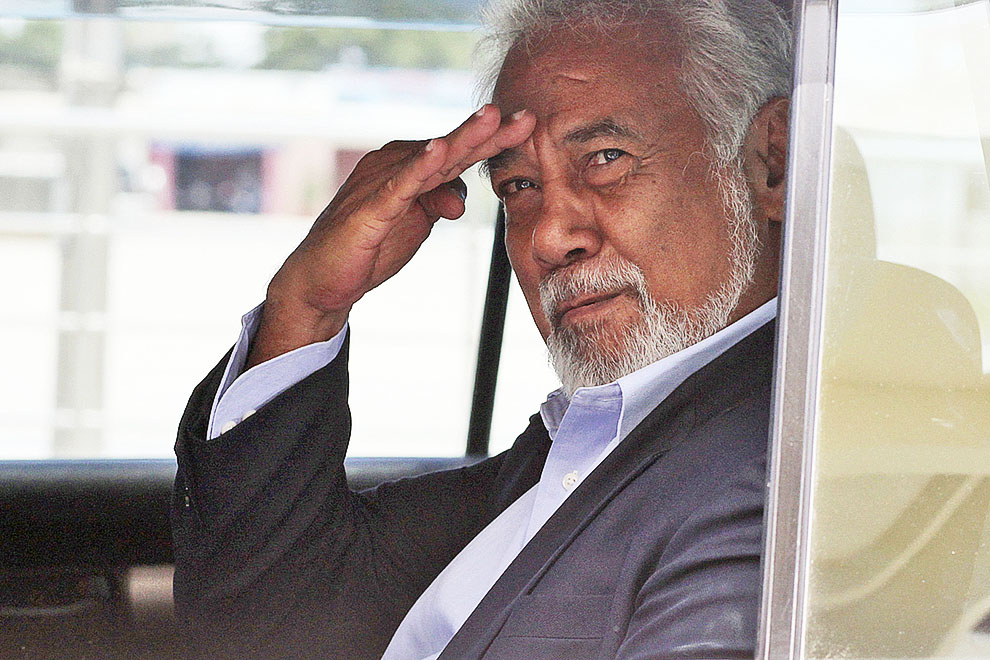

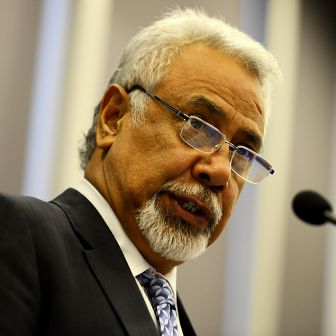

Visiting Marces Beach Paintball in Hera, outside Dili, is a new pastime for Dili’s emerging elite and expat communities. The place was established by two young, English-educated Timorese men who import paintball equipment and other more serious technologies from Europe. On this day in January I’m one of the parents watching a group of kids battle it out, and the man sitting next to me happens to be the former president and prime minister, Xanana Gusmao, who these days is Timor-Leste’s planning and strategic investment minister.

The paintball players are using Airsoft guns to shoot soft plastic balls full of fluoro paint, which explode on contact and mark their opponents as “dead.” The balls can hurt, so the kids wear protective clothing – fake military camouflage outfits, chest protectors, helmets and masks. Still, my daughter, the only girl among the players, will go home with half a dozen bruises.

The playing field is made to look like an urban frontline. The kids have been split into teams and placed at either end of the field with the aim of capturing each other’s flags. They have fun arguing about who shot whom, and who has ultimately won the battle. Their personalities crystallise in the playing of the game: one, easily distracted, is shot early and often; another, playing safely and carefully, avoids being shot but never wins a battle; another is reckless, shooting off rounds and rounds, running out of bullets and being forced to retire. My daughter becomes careless in her mission to prove she is tougher than the boys, and even takes a potshot at Xanana. The most frequent winner is a daring and sometimes reckless boy who is also focused and strategic. His team wins nearly every game.

I started off laughing with Xanana at the kids’ antics and disagreements. Then, as he started advising his sons from the sidelines on guerilla tactics, I watched and listened. “Move up, move up and get behind the can.” “Don’t shoot your bullets all at once, keep them and fire them occasionally to keep the enemy guessing.” “Try to get around the back and shoot from behind.” It was a reminder of his deadly past and the things he’d had to do during the Indonesian occupation of his country – a reminder that we were standing here playing at war because he’d actually fought one. But the kids didn’t obey his commands; they were intent on their own game plan. They didn’t think of him as an ex-guerilla soldier with direct experience of war. For them he was just a dad, by his own admission not fit enough these days to join in the battle.

Many others in the new nation, though, still think of Xanana as the Commander. The week before the paintball game, I made a return visit to the village of Bauro in the country’s far-east with Xanana’s former wife, Kirsty Sword Gusmao. She wanted to visit Jacinta Nogueira, who had supplied food and water to Xanana when he was in hiding during the worst period of the Indonesian occupation. Avo (or grandmother) Jacinta looks many years older than her age, her face engraved with deep lines of sadness, and she wept when she realised Xanana was not with us. I had last seen her in 2001, when I was researching my biography of Xanana and she had shown me his old hideout. Along with her remaining family, including teenagers and barefoot children, she had taken my three companions and me on the same bush trek she’d made often twenty years earlier.

We had climbed over old stone walls overgrown with lantana, which had to be cleared by the two machete-wielding men in the lead. The track was overgrown, too, and people became confused and started to argue about the way. It was slow going and, as the morning marched towards midday, the temperature rose. At one point we emerged from the undergrowth into a hot, flat area, stumbled across sharp black coral, and then dove back into the scrub. I began to think about how fearful the guerillas must have been to have hidden so deep in the bush: how real and present the danger must have seemed to take such enormous precautions; how secretive it would have made them.

Suddenly we came down a little crest and then, as we turned the corner, I saw my friend disappearing like a rabbit into a hole set in some rocks. The little boys were crowded around the entrance and someone began to hand out earthenware bowls. These were the vessels, Avo Jacinta told us, in which she used to carry the food to the fighters. I was amazed; they had been down there for twenty years, untouched. No one had disturbed this place in all that time. No one had even talked openly about its existence until now. My friend called from inside that there was a second little room with a bamboo sleeping platform that was Xanana’s. I looked inside the room by torchlight; it was tiny and claustrophobic. Only a desperate person, I thought, would sleep there.

We sat on the rocks and grass around the cave as one of the village women told their stories. Avo Jacinta’s husband and only son were executed in retribution for her having helped Xanana; her husband’s hands were cut off before he was killed. The village surrendered to the Indonesians and many were killed and tortured during the eighties. Avo Jacinta nodded her head and let her story be told in English, a language she doesn’t speak.

These stories from that period are remembered in Timor and hugely significant in the new society. A hierarchy based on past service to the resistance has been established, and in this society Xanana remains the Commander, or Maun boot, the big brother. Pensions and payments to male veterans are one of the biggest expenses for the government, and veterans are favoured for important government positions and in the awarding of government contracts for national infrastructure. Outsiders see it as a kind of corruption; the veterans see it as their due. Anthropologists have described an indigenous belief that those who fought and sacrificed “purchased” the nation with their own lives and are therefore owed a living.

In February last year Xanana resigned as PM and handed that job over to Rui Araújo, a younger man with more formal education. After much factionalism and fighting, a stable middle ground appears to have been created in Timorese national politics. The decision to relinquish power won praise for Xanana. The new government might just be the government of national unity that he has been seeking since the early 1980s, reflecting a mode of indigenous political consensus. The nation feels more stable, reflecting the apparently peaceful transfer of power from the older leadership of veterans to a younger leadership of educated professionals.

Yet Xanana has remained deeply engaged in the government as the minister responsible for the new super-ministry covering strategic planning and economic development. He has cherrypicked important portfolios from other parts of the government, overseeing the national development planning process and budget. He retains a strong influence over oil and gas resources and government contracting, and influential relationships with key ministers who owe him their positions. He has “his hand on the tap,” as Timorese say, able to turn on and off the water supply to the rest of government.

Xanana has taken himself further and further from the spotlight. He has moved out of the Government Palace and into an out-of-the-way office. He has fewer and less-experienced staff, and few advisers. But perhaps, from there, he still leads much as he did from the hideout in Bauro: through trusted couriers and lieutenants, strategic relationships with outsiders, and little counsel but his own. In Timorese political culture he is the grandfather and primary patriarch, a virtual deity to many of the ema kiik, those on the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder, who survive in deep poverty. For them, Xanana remains the Commander, but what now is the war? •