“Ni avec toi, ni sans toi.” If Britain’s long and often tortuous relationship with the European Union could be summed up in a single phrase, the epigraph of François Truffaut’s film La Femme d’à Côté is a good candidate. Across seven decades, the two sides have been enveloped in fluctuating tides – of politics and history, of interest and emotion, of loyalty and ideology, of reason and longing – without ever settling into a definitive resolution. “Neither with you, nor without you,” indeed.

If truth be told, though, they shared little of the passion of Truffaut’s doomed couple. Britain’s early encouragement of continental cooperation in the late 1940s; its protracted negotiations over the infant European Economic Community in the 1950s; its twice-vetoed applications to join in the 1960s, and the successful bid in the 1970s; wrangles over budgets, labour rights and exchange rates in the 1980–90s and tensions over the new European Union’s constitutional treaty in the 2000s; and the eurozone crisis in the 2010s – through all this, the story has been one in which rows have often given way to hard-won agreement, yet also in which divorce was no more feasible than real intimacy.

Now, in 2013, comes a new chapter that offers the possibility of a radical break. In a long-delayed and much-trailed speech on 23 January, prime minister David Cameron announced that four years hence he intends to hold a referendum on whether Britain should stay in the European Union. Departure is not his preferred option. The speech delineates a series of principles for a reformed European Union (competitiveness, flexibility, devolution of power, democratic accountability, and fairness); if they can be codified to Britain’s advantage in negotiations with other member-states, they would allow Cameron to recommend that the British vote to stay in the union.

The very act of putting withdrawal on the agenda changes the terms of political trade in Britain in four ways. It addresses the deep divisions within the governing Conservative Party on the European issue (and though in no way resolving them, does buy Cameron time with his increasingly febrile party). It establishes greater distance from his (pro-European) Liberal Democrat coalition partners. It sets down a marker that Cameron intends to fight the election due in 2015 and stay in power beyond. And it takes the initiative against Ed Miliband’s Labour Party, challenging it to clarify its own (so far ambiguous) position on a referendum.

In itself, though, Cameron’s manoeuvre secures no guarantees about the future. His party is polling around 10 per cent behind Labour, which makes its chances of winning a parliamentary majority next time look slender; the promise of a referendum has had no effect on voters, while reinforcing the conviction among the party’s more hardline anti-EU voices that the future belongs to them; and the new constitutional timetable complicates Cameron’s strategy towards the other “in-or-out” referendum – namely Scotland’s. (On 30 January the Electoral Commission prescribed the wording of the question Scottish voters will be asked in autumn 2014: “Should Scotland be an independent country? Yes/No.”)

For the “yes” side north of the border, a protracted argument about Britain’s position vis-à-vis Europe creates welcome opportunities. This is less because (as some polling evidence suggests) the Scots are more “pro-European” than their southern neighbours and more because independistas see the chance to portray Cameron’s effort to reclaim powers from Brussels as validating its own stance towards London. Moreover, the potential of the Scots to turn any 2017 referendum into a vote about the place in the European Union of England, Wales and Northern Ireland will concentrate minds. Complicating things even further, a “yes” vote in 2014 would leave the details of Scotland’s independence and its relation to Europe to be negotiated with London and Brussels, to name only those. The London part especially – from oil revenues to nuclear weapons via pensions, currency and diplomatic assets – would not be easy, whoever is in charge at Westminster.

In these circumstances, most voters might end up opting for the status quo – Scotland in Britain, Britain in Europe – in search of a simple life. Most recent polls show a majority in favour of leaving the European Union (one in the Financial Times on 18 February reports the out–in numbers as 50–33 per cent), though they also suggest that Europe ranks a low fifteenth among the issues of importance to voters. But the mere fact of the new timetable – which includes elections to the European parliament in 2014, and the 2015 general election – increases both the stakes and the risks for David Cameron.

There are early hints following his big speech that his preferred negotiating track might prove smoother than many had reason to expect. The initial response among his fellow leaders – most significantly Germany’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, the union’s pivotal figure – was more accommodating than hostile. The EU summit on 7–8 February produced a budget deal for 2014–20 that, at €960 billion (A$1230 billion), represents a 3 per cent cut on the current seven-year cycle. Cameron’s newly proactive stance on the union’s future may have contributed to that outcome (though the European parliament’s endorsement of the budget is far from certain). More generally, the long eurozone crisis – albeit in remission following the European Central Bank’s pledge in September 2012 that it would make “unlimited” purchases of sovereign bonds – has exposed the European Union’s institutional problems and made another tranche of reform essential. True, most in the eye of the currency storm argue that the direction must be towards deeper integration rather than the loosening Cameron wants, but the very fact that his agenda is now explicit may prove useful in bringing the core European arguments into focus.

THE focus is also inevitably retrospective. A formal process that could result in Britain’s departure from the European Union takes its place amid the knotty relationship that unfolded over the post-1945 decades. (Among the library of books devoted to the topic, Hugo Young’s This Blessed Plot: Britain and Europe from Churchill to Blair, published in 1998, is still among the freshest.)

Some of its broad themes are traceable to an even more distant past. Among them are the eighteenth-century efforts of the British empire-state to maximise its freedom of action and minimise continental entanglements while standing ready to contain any major European rival. Horizons were further enlarged by global commitments that developed in step with the high tide of empire in the nineteenth century. (John Darwin’s Unfinished Empire: The Global Expansion of Britain, published in 2012, is a brilliant synopsis.) Underpinning Britain’s fleeting moment of dominance on the world stage was a cohesive elite possessed of an ingrained belief in its far-reaching mission – and of the weapons necessary to enforce it. The cataclysm of 1914 foreshadowed a decline in power that the rise of the United States and the challenge of Germany had already intimated; the troubled interwar years were a holding operation as new and threatening forces – protectionism, anti-colonialism, totalitarian state-forms – took root.

The second world war brought a victory tempered by exhaustion, near-bankruptcy and the prospect of strategic retreat (not least from the empire’s keystone, India). The scale of indebtedness to Washington was symbolised by the latter’s dominance over the new World Bank and International Monetary Fund. (Benn Steil’s recent book, The Battle of Bretton Woods, encapsulates the power shift in its portrait of the unequal relationship between Britain’s John Maynard Keynes and US treasury official Harry Dexter White.) Nonetheless, the war had given Britain, in Hugo Young’s words, an “exquisite sense of national selfhood, and the experience of vindication” that accompanied it.

The conflict left Europe shattered and divided. Apart from a necessary share of responsibility for control of postwar Germany, the continent’s political future was low among Britain’s priorities. Under Clement Attlee, Labour won a landslide victory in the 1945 election on a program with domestic rebuilding, state control of industry and social security at its heart. (“Food, work and homes” was among the formulations of its elegant manifesto, “Let Us Face the Future,” drafted by Michael Young.) Overwhelmingly, “overseas” still meant the empire (or as it increasingly became referred to in polite circles, the Commonwealth). There was little interest in Europe as such, let alone the scarcely imaginable idea of its political coordination.

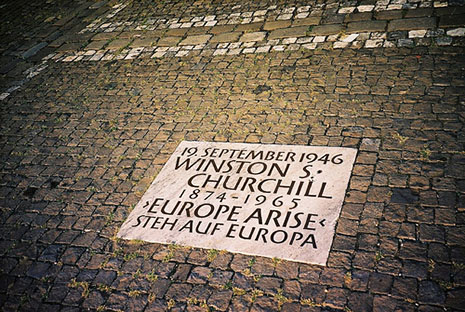

It was the wartime leader Winston Churchill, now in opposition, who put his vaulting rhetoric to the service of the idea of continental unity in a series of speeches. In Zurich in September 1946, for example – six months after his more famous “iron curtain” address in Missouri – he proposed “a structure” under which “the European family” could find peace, safety and freedom. “We must build a kind of United States of Europe,” with its first step “a partnership between France and Germany.”

The vision drew on interwar “pan-European” initiatives, whose aspirations were soon to be embodied in such groups as the Union of European Federalists and the European Movement. It, or variants, was shared by politicians such as Jean Monnet, Altiero Spinelli and Paul-Henri Spaak, for whom the very scale of wartime destruction – spiritual as well as material – meant that the route to realism lay through grand ambition. In addition, exiled Europeans who had found shelter in London during the cataclysm believed that Europe’s rebirth after two civil wars within thirty years demanded new forms of association. It seemed to some that the moral capital Britain had accumulated by standing alone in the depths of the war – however skewed a picture this was, given the country’s imperial and Atlantic lifelines – invested it with a unique capacity for leadership in what they hoped would be a common task.

The idea of European unity as a socialist project was to have some traction among parts of the non-communist left. George Orwell, for instance, wrote an article in its favour in 1947, published in Partisan Review. (“A western European union is in itself a less improbable concatenation than the Soviet Union or the British Empire.”) The freezing of Europe’s east–west division by 1947–48 was part of a complex of elements – including the dislocations and uneven pace of economic recovery, the US re-entry to Europe with the Marshall Plan, and the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany in May 1949 – that accelerated the search for mechanisms of closer transnational cooperation.

Britain was deeply involved in all these developments. But a Labour government striving amid straitened circumstances both to deliver results at home and to reaffirm the nation’s great-power status saw little reason to join any “federal” initiative on the continent. It remained outside the Schuman Plan of 1950 that gave rise to the European Coal and Steel Community in 1952, the nucleus of the six-member European Economic Community, or EEC, created in 1957.

The strategic choices of the immediate postwar years extended through Churchill’s last hurrah in government in 1951–55. In the following year came his successor Anthony Eden’s Suez adventure, with a British-French-Israeli attack on Nasser’s Egypt, founded on diplomatic deceit, ending in worldwide obloquy and humiliating evacuation. The crisis shredded illusions about Britain’s power, convulsed the political order, and opened a generational divide. In the aftermath, the search for a direction included the formation of a European Free Trade Association with six of the smaller European states in 1960. This “spoiler” operation brought as few benefits as did Britain’s efforts to play an “honest broker” role in the new superpower rivalry. The response to this stream of failures brought a repositioning, if not a fundamental rethink (Britain doesn’t do those): make the most of an inevitably subordinate strategic alliance with the United States, and strike out politically for membership in the EEC.

Neither proved an easy ride. In 1963, Charles de Gaulle vetoed the request of Harold Macmillan, the latest patrician Tory prime minister, to join what London called the “common market.” De Gaulle cited Britain’s Commonwealth trade preferences and its military bonds with the United States as barriers; he might have added that Britain’s references to a “common market” indicated a much narrower commitment than the pledge of the EEC’s Treaty of Rome “to lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe.” The French president delivered a second veto to Labour’s would-be moderniser Harold Wilson in 1967. But de Gaulle’s retirement in 1969 opened the door, and on 1 January 1973, after the lengthy process of acquis communautaire (member-state incorporation of European law), Britain – holding hands with Ireland and Denmark – at last walked through.

THERE is an appropriateness in the fact that Britain’s entry to the EEC was led by Edward Heath, who inflicted a surprise defeat on Wilson to return the Conservatives to power in 1970. Heath is the sole “ideologically” pro-European figure of Britain’s thirteen postwar prime ministers. But this personal triumph, along with his ambition to transform the economy, soon foundered on hyperinflation and trade-union muscle, and Wilson was back after a four-year interregnum. His Labour Party, however, was just warming up for a fifteen-year civil war in which Europe amplified the deep divisions between a pro-EEC right and a withdrawal-demanding left. The splits reached into the cabinet too, leading Wilson – following a cursory “renegotiation” over budget contributions and New Zealand’s dairy produce – to hold a referendum to ratify the new terms, thus fulfilling the promise of Labour’s election manifesto.

It was all very new: the first ever UK-wide referendum. (The second, on the alternative vote, had to wait until 2011.) Clement Attlee had described the referendum as “a device for despots and dictators.” This was long the consensus view of a British political class which both took for granted the superiority of the Westminster model of “parliamentary democracy” and assumed that referendums could find no place within it. But this system’s genius (or if you wish, its hypocrisy, though perhaps they amount to the same thing) is to embrace incremental change while affirming that everything – most of all, the diamond-hard sovereignty of the “crown in parliament” – remains as it was. By July 2011, when the new European Union Act prescribed a referendum over any amendments to the constitutional treaties governing the European Union, the device had become a hallowed tradition.

The suspension of collective responsibility at cabinet level eased inevitable tensions and aided a vigorous campaign, with 67.2 per cent voting in June 1975 to remain in the EEC. The journey “from rejection to referendum” – as the senior diplomat Stephen Wall has it, in the compendious second volume of his official history – was complete. Honour was sated, Labour’s right elated, its left deflated; and Europe as a political issue died. Or, rather, as it turned out, hibernated.

EUROPE had always been the source of tensions in both parties. Labour’s post-Attlee leader Hugh Gaitskell, influential to a generation of the party’s right, declaimed to its conference in October 1962 that EEC membership would be “the end of a thousand years of history.” The Tories’ pro-imperial voices agonised over a retreat from a world role, the party’s sterner cold-warriors over the fraying of the coveted “special relationship” with Washington.

Such attitudes reflected the lack of positive strategic definition in Britain’s thinking about itself since the war. Everything, it came to seem by the 1970s, had been improvised. In October 1947 Churchill had described Britain as being at the centre of “three overlapping circles” of power – the Commonwealth, the Atlantic Community, and Europe. (“Young man, never let Britain escape from any of them,” he told the new ambassador to Washington.) Allowing for a rhetoric made windier by the absence of war, the heroicising metaphor strained at the seams before new geopolitical realities.

The lack of definition conjured a world where policy was ever a “response to” rather than a “shaper of.” It also had its absurdities – none greater than the way that senior British diplomats in the 1950s spent much time propitiating imaginary American worries about any shift by London towards Europe. The settled view in Washington was mordantly realistic, and all the other way. Dean Acheson, former US secretary of state and an adviser to President J.F. Kennedy, spoke in December 1962 of prospective British membership of the EEC as “another step forward of vast importance,” and dismissed “Britain’s attempt to play a separate power role” via its various international associations as “about played out.” His words read like a direct riposte to the pro-American Gaitskell.

There is a contemporary echo here in the mismatch between the views of Tory hawks, who fear that Britain will “lose” America if it maintains a pro-European stance, and the warning against British withdrawal delivered in January 2013 by Philip Gordon, the US assistant secretary of state. Harold James – author of Making the European Monetary Union, published in 2012 – sees Washington as the interloper; the current situation, he says, is “a Shakespeare comedy of confused identity. Europe and Britain are married, but Britain wants to deepen its relationship with the US, while the US cares more about Europe.” In that case, the new momentum behind a US–EU free-trade pact – the subject of a high-level joint statement on 13 February – might yet throw all partners into a bewildering ménage à trois.

THE contours of the European question in domestic politics – and its American dimension – again shifted in the 1980s as a result of Margaret Thatcher’s instant bond with Ronald Reagan and more gradual alienation from her European partners. As a young education minister in Heath’s government and then (from 1975) as Conservative leader, Thatcher had been pro-European, and she campaigned strongly for a “yes” vote in the referendum. But as prime minister – after surviving shaky early years to emerge with a confident international profile – the narrowly financial focus of her European diplomacy became a source of tension. The case that Britain was over-paying was made, but as rebates were secured so was a reputation for abrasive nationalism.

The tensions belonged to political culture as much as policy or even personality. Here was a leader enjoying the near-untrammelled power allowed by Britain’s executive-centred system faced with a pluralistic, coalitionist, deal-making continent ever inclined to the “compromise” she loathed. Yet she also made the deals, not least the Single European Act of 1987 that was the basis for later consolidation.

At the apex of Thatcher’s reign in September 1988, the vision of Britain in Europe elaborated in her Bruges speech – drafted by her close adviser Charles Powell – rejected the notion “of some cosy, isolated existence on the fringes” but also affirmed that “willing and active cooperation between independent sovereign states” is the route to a successful European Community. The way ahead was a practical, outward-looking, reforming, free-trading association that seeks to “work more closely on the things we can do better together than alone” yet avoids the temptation to “try to suppress nationhood and concentrate power at the centre.”

The stiletto was in a single sentence: “We have not embarked on the business of throwing back the frontiers of the state at home, only to see a European super-state getting ready to exercise a new dominance from Brussels.” It was aimed at the heart of Jacques Delors, president of the European Commission. Days earlier, he had been warmly received at the conference of Britain’s trade union movement when he proposed that the “social dimension” of the single market offered real opportunities for workers to secure new rights.

Each address reverberated among its intended constituency. Among the results of Thatcher’s was the formation of the Bruges Group; of Delors’s, a burgeoning affection for Europe on Britain’s centre-left, partly on the “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” principle. But the political weather was soon to change in unexpected ways: intransigence and cabinet division over Europe corroded Thatcher’s power, and her replacement as party leader by the unobtrusive John Major in 1990 gave the Tories an extended lease in office. Major’s complaisant aura had made him the great grey hope for those – after eleven and a half years, most of the party – seeking Thatcherism with a more human face. But his post-election authority, already hedged by a slim majority in the 1992 election, was destroyed by Britain’s chaotic exit from the proto-euro “exchange rate mechanism,” or ERM, later that year. His endorsement of further EU harmonisation in the Maastricht treaty made him the enemy of the now-coalescing “Eurosceptic” tendency.

WHAT was, is, “Euroscepticism”? The term emerged in the early 1990s as a useful shorthand for a sentiment that animated much of the Conservative Party and the media; flowed through many in the Labour Party and wider left; and inspired the formation of the United Kingdom Independence Party, or UKIP, in 1993. It also elided proper distinctions between outright opponents of British membership of the European Union and critics who would accept a reform of its terms. In practice – because the former were noisier, punchier and more visible – it tended to make public argument about Europe more absolutist and undiscriminating. It also tapped into broader emotional and psychological currents – fear of loss and change, of immigration and the other, of shadowy string-pulling elites – that in post-Thatcher Britain had greater appeal on the political right.

This messiness was both strength and weakness. It allowed the European Union’s opponents to tie their case to the wider, ever-resonant narrative of national-moral decline, but it also made a strategic focus on particular issues harder. In turn, it reflected the fact that Euroscepticism was a coalition in which those with varying priorities – withdrawal or reform, identity or policy, moralistic conservatism or free-market liberalism, defence of national sovereignty or resistance to a “capitalist club,” a more globally oriented or a more localised economy – found common cause. The single label acted to empower but also to mislead: many “sceptics” were more truly “Europhobes,” others were “Eurocritics” or (as some preferred to say) “Eurorealists,” though none of these terms – and even less “Europhiles” – gained purchase.

The differences mattered little under Major’s premiership, which was dogged by the ERM fiasco, bruised by scandals, and menaced by a Labour opposition at last recovering from the traumas of the 1980s. Its wipeout by New Labour in 1997 was a blessed release. But the Conservative purgatory only deepened in the new political era. The party’s next three leaders – William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith, and Michael Howard – tacked to the right but still failed to propitiate the Eurosceptic monster that had gripped it. After three election defeats, David Cameron took the helm in 2005 with a promise of modernisation and a warning to colleagues and grassroots in 2006 that it was time to “stop banging on about Europe.”

Most Conservatives, by that stage, were ready to listen. A party that lived for winning and wielding power was tired of losing. The image of the party projected by the more intransigent Eurosceptics – obsessive, punitive, negative – had come to define the Conservatives as a whole to much of the electorate, including the non-aligned whose support they needed to regain power. A party that always saw itself as representing the nation had allowed its social antennae to shrivel. It was prepared to give Cameron’s makeover a chance, even if the latter’s showier elements (such as a visit to the Arctic to express passion about climate change) conveyed the sense of a necessary fiction.

To a degree, the process worked. Europe did indeed recede as an issue in domestic politics. The European Union was coming to terms with the major enlargement of 2004, when ten states (mainly in eastern Europe) joined, to be followed by Romania and Bulgaria in 2007. And it was engaged in an arduous negotiating process to agree a new constitution for the now twenty-seven-member body (with more to come). The former could plausibly be seen as a delayed vindication of Margaret Thatcher’s insistence (including at Bruges) that Warsaw, Prague and Budapest were at Europe’s heart; the latter tended to reinforce the old fears of a move towards a continental superstate. For Eurosceptics, after all, this was the true monster, and it was always likely that they would be back to grapple with it.

By 2010 several factors were conducive to a fresh surge of Eurosceptic feeling. Cameron’s victory in the election of that year, which also brought to his backbenches a new cohort of energetic, right-leaning MPs, had ended a political cycle dominated by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. Immigration from the new accession countries was unexpectedly large-scale. The UKIP had survived and prospered, gaining 16.5 per cent of the vote (and thirteen seats out of seventy-three) in elections to the European parliament in 2009. Britain’s economic anaemia since the crisis of 2007–08 had increased the appeal of radical and populist fixes. And, most of all, the eurozone had imploded, threatening wholesale financial breakdown and pushing EU leaders to consider more integration as the only long-term prophylactic. The eurozone calamity both vindicated the decision to stay out of the single currency (initially Major’s, then Brown’s against pressure from Blair) and shone as the jewel in the Eurosceptics’ crown: a unitary Europe spells disaster.

This precarious conjuncture makes the prime minister’s referendum démarche on 23 January all the more intelligible, and his craftsmanship in turning a political trap into a tryst with destiny all the more impressive. It will soon become clear whether it proves to be a bravura effort to reshape the agenda by creating a new political current (the “Euroreform-and-then-stay-in-ers”) or a more desperate holding operation against the “Brexit” tide. (An excellent new book by David Charter, Au Revoir, Europe: What If Britain Left the EU?, examines the options, and even poses the big question – adieu or au revoir? – in Truffaut-esque fashion.)

AT THIS stage, the opening of a new phase in Britain’s forty-year marriage with the European Union suggests four conclusions. First, so polarised has this debate been for so long that it will be very hard to establish even a shared definition of its terms as a basis for the detailed public discussion to follow.

Second, there will be more fissures and realignments inside as well as between both main camps. It may be, for example, that the incompatible visions within the Eurosceptic pantomime-horse – the populist anti-immigrant moralisers of the UKIP, the localising eco-left, and the globalising libertarians – will at last properly be explored. The argument that Britain can and should become a flexible, dynamic, low-tax hub of world trade – and that this is the exit-route from economic stagnation as well as from Europe – needs to be made, as does the argument that only a radical shift towards a more settled, hi-tech, low-carbon economy can ensure prosperity and security.

Cameron’s “Euroreformers” – as they may come to be called – will also find it hard to build a cohesive coalition in favour of the endgame the prime minister seeks. Some outflanking will come from the contentedly pro-EU side as business lobbies and new pressure groups mobilise; and internal Tory pressures will accentuate as EU reform (and eurozone integration) evolve between now and 2017. (The perceptive Alex Massie even predicts these will result in a split – though perhaps the UKIP is, in effect, that split).

Third, for all the appeal of declinism, elections (and referendums) in Britain tend to be won more by optimism. This is bad news for gloom-spreading Europhobes (and, insofar as they dominate the Eurosceptic camp, the latter as a whole), and may in the end – despite current evidence – be good news for independence campaigners in Scotland.

Fourth, the “in or out” question is also the latest episode of displacement in this, the genre’s master-country. Much of the post-1945 history reviewed here can be read as one of abortive modernisations – with Wilson, Heath, Thatcher, Blair and now Cameron as the leading cast. In this long-running play, “Europe” is – and perhaps always was – a convenient hook on which to hang a problem that is actually internal to the country: an unresolved sense of its post-imperial place in the world.

In this larger frame, the next several years begin to look even more testing for a Britain more confident with its past than comfortable with any of the futures on offer. Perhaps the machinery of governance will continue on its adaptive way – after all, muddling through is arguably not just what Britain does, but what it is. For all that, a country used to evading clear choices for so long may one day find that it has lost the ability to make them. •