One hot evening in March 2000 I drove to the outer eastern suburbs of Melbourne to see immigration minister Philip Ruddock addressing a community consultation on migration. Refugees and asylum seekers had been in the headlines, but the most passionate debate that night centred on another issue altogether: parent visas. Although they rarely rate a mention in the mainstream media, these visas for parents of permanent residents have continued to arouse great passion as ministers have come and gone.

Now, the Turnbull government is attempting to manage the problem by introducing an entirely new five-year temporary visa, commencing next July. With the immigration department apparently unable to provide basic information about how great the demand for such a visa might be, it looks like a political fix rather than a coherent policy initiative, and is likely to create a new set of problems. To understand how we arrived at this point, it helps to go back to Melbourne’s outer eastern suburbs on that March night more than a decade and a half ago.

In his opening presentation, Philip Ruddock proudly described the government’s success in swinging the pendulum of permanent migration away from family reunions and towards skills. Under the Hawke and Keating Labor governments, family visas had made up around two-thirds of all places in the migration program; after the Coalition took office under John Howard in 1996, the share soon fell to less than half. (Since then the share has fallen further; for many years now, the family stream has made up only about a third of the permanent migration program, or 57,400 of 190,000 places in 2015–16.)

Ruddock bolstered his bias towards skills with numbers. According to the neat charts he projected onto the screen, every 1000 people who entered the country as skilled or business migrants created a net gain to the federal budget of $36.7 million over five years. The same number of family migrants, by contrast, cost the budget $1.8 million. And because not all family visas were alike – migrant parents impose “a significantly higher ongoing cost” than spouses and partners, for instance – he had changed the character of family migration by capping parent visas at 500 places per year. With 20,000 applications pending, he cheerfully revealed, the waiting time to bring aged parents to Australia was roughly forty years.

For many in the audience – Australians of migrant backgrounds who were keen to find ways of bringing older relatives to join them here – that last piece of information wasn’t at all cheering. But it wasn’t news. Ruddock’s capping of parent visa numbers was one salvo in a war of attrition with the Senate. In 1998, the Coalition had attempted to manage the growing demand for parent migration by introducing a contributory parent visa, which would have allowed sponsors to bring their parents to Australia as permanent migrants as long as they were willing to stump up $17,000 – a revenue-raising measure designed to offset some of the costs these migrants might impose on the community as they aged. Labor and the Senate crossbenches initially disallowed the new visa on the basis that it amounted to “queue jumping”: the rich would have the capacity to bring their parents swiftly to Australia; the poor would wait forever. Ruddock returned fire by imposing his 500-place cap.

In Knox that night, I saw how this blunt instrument had swung many migrant families to his side. Given the choice between an indefinite and uncertain wait for an affordable parent visa and a relatively short wait for an expensive one, they would choose the latter. I recall passionate pleas from participants at the consultation, promising to take full responsibility for their parents living expenses, to provide for their housing and to guarantee their healthcare costs, if only the minister would allow them to bring parents to Australia quickly. The government had to understand how crucial it was in their culture to honour and care for your parents in their elder years, and how essential it was for grandchildren to know their grandparents and hear their stories. If required, migrant families of all backgrounds were willing to pay large sums to get their parents to Australia.

Ruddock’s tactics were ultimately successful. When the Senate relented in 2003, the contributory visa immediately became the main mechanism used by families to bring parents to Australia. In 2003–04 the cap on parent visas was raised from 500 to 5000 places, but around 70 per cent of visas were in the new contributory category. In recent years 80 to 85 per cent of parent places have been set aside for contributory visas. (In 2015–16, this translated into 7175 out of 8675 parent places.) If the Coalition government had got its way, the non-contributory parent visa would have disappeared altogether. It tried to abolish the category in 2014, but was again stymied by the Senate.

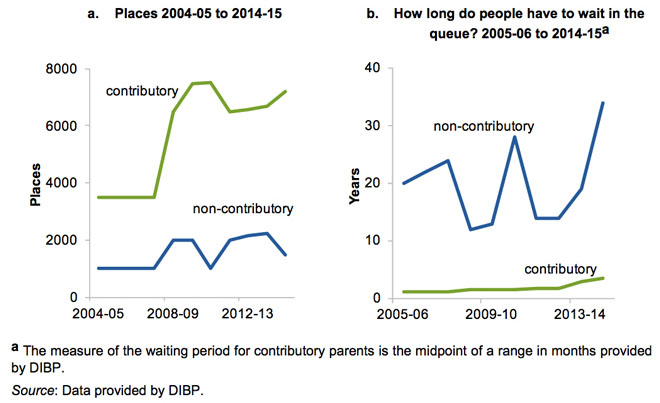

Predictably, the cost of the contributory visa has also increased sharply over time, from $26,200 when it was introduced in 2003 to $47,295 today (and this doesn’t include the cost of migration advice or outlays for such things as medical checks and police reports). Despite the high charges, the federal government has no trouble filling its annual quota, and there are almost 30,000 applications in the pipeline. Applications are usually finalised within two years of being lodged, although as the right-hand graph in this chart from the Productivity Commission shows, processing times have been lengthening.

In the parental queue: places and waiting times

Source: Productivity Commission, Migrant Intake into Australia, figure 13.3.

As the graph shows, however, the waiting time for a non-contributory visa (which carries a base visa application charge of $3870) is much longer; currently it is a ludicrous thirty years, so only relatively young parents would have much hope of living to see their visa issued. Despite the wait, there is nevertheless a backlog of more than 50,000 applications. Clearly there is huge pent-up demand for parent migration, especially when you consider that applicants for the two parent visas must also satisfy the balance-of-family test: at least half the parents’ children must be living permanently in Australia, or they must have more children living permanently in Australia than in any other country. Tens of thousands of potential parent migrants no doubt fail to meet these criteria.

This unsatisfied desire to bring parents to Australia has fuelled what might seem like a paradoxical campaign for a new, temporary visa category for families that don’t meet the balance-of-family test, or can’t afford the expensive option of permanent migration under a contributory visa and don’t want to suffer the indefinite wait for a non-contributory visa.

It’s important to be aware that migrant families are already bringing parents to Australia on temporary visas. For now, however, their options are limited to a maximum twelve-month stay on a subclass 600 tourist visa. When that visa expires, the foreign parent must leave Australia and remain outside the country for at least six months before applying for another visa.

Frustration with this arrangement coalesced into a concerted campaign for a temporary “long-stay visa for parents.” Adelaide bus driver Arvind Duggal, who was instrumental in getting this campaign off the ground, told SBS that the visa restrictions prevented him from fulfilling his responsibilities as a son and that he was tired of answering his children’s repeated questions about why grandma was leaving again. Duggal’s appeal struck a chord: two years ago he started an online petition to immigration minister Peter Dutton that has now attracted almost 30,000 signatures. Migrant communities saw an opportunity in the lead-up to the 2016 election. They lobbied Labor and the Coalition on the issue, including in marginal electorates, and both parties responded with apparently hasty campaign promises that passed largely under the radar of the media. Labor pledged a temporary visa that would allow parents to remain in Australia for three years and would only require them to leave for four weeks before qualifying for a renewal. A few days later, the Coalition upped the bidding, promising a five-year parent visa.

The final factor in the mix that may have influenced the government’s thinking on a temporary parent visa was the Productivity Commission’s report into Australia’s migration intake. The report suggested a new “provisional visa” that “would permit parents to stay for a longer period of (say) five years” and could, “after a given period of absence from Australia, be renewed multiple times.” While the commission’s report was not made public until well after the election, it had been presented to government in April 2016, about a month before the campaign kicked off. So the idea of a new temporary parent visa may well have been knocking around already in the heads of immigration department officials and ministerial advisers.

Returned to office, the Turnbull government moved relatively quickly to make good on its election commitment. On 23 September, assistant immigration minister Alex Hawke announced a series of community consultations on the design of the new visa. The immigration department also published a discussion paper and called for public submissions to be lodged by 31 October.

Supporters of Arvind Duggal’s push for a long-stay parent visa were elated. “My heart is in celebration by the chance of having my mum close to me for longer than six months sporadically,” wrote Viviana Aroujo on the campaign’s Facebook page. “I cannot express how happy I am for reading this media release… having my mum for at least three years near her only grandchild is a dream… Gosh, I am in tears!!!!!!!”

The Productivity Commission looked at the issue with much drier eyes. Its support for a temporary parent visa was motivated less by any emotional and physical well-being that results from bringing families together than by the huge future costs of the system of permanent parent visas, whether contributory or non-contributory.

The commission’s argument goes like this. Compared to other immigrants, parent migrants are likely to have weaker English-language capabilities, fewer skills, lower personal incomes and lower volunteering rates, thus reducing their chances of forming “deep and broad community connections.” True, “immigrant parents can make valuable social contributions to their families,” but these “mainly benefit the family members themselves.” Even when unpaid childcare is provided, for example, this essentially amounts to a private benefit – in the form of family savings on childcare costs – rather than a public good. Indeed,the “need for childcare is greatest for infants, and so often not enduring,” whereas “the responsibilities of taxpayers for supporting the parent visa stream apply throughout the rest of their lives.”

The long-term costs of supporting parent migrants were the commission’s main concern – and according to its calculations, those costs are considerable. It estimated the “cumulative lifetime fiscal costs” of a migrant parent on a permanent visa in 2015 to be “between around $335,000 and $410,000 per person (with the ‘best’ estimate being just over $370,000).” As the report concluded, “the current contributory visa charge of $47,295 meets only a small fraction of the fiscal costs for the 7175 contributory parent visa holders in 2015” (while the 1500 non-contributory parent migrants make an even less significant contribution).

The commission calculated that the net liability for providing assistance to the 8675 parent visa holders who arrived in 2015 was, over their lifetimes, “around $2.9 billion.” Even if there were no increase in the number of parent visas issued each year, it estimated, the costs to the Australian community of permanent parental migration would still be between $68 billion and $85 billion from now to 2050. (The commission noted in passing that this cost might rise even further due to “the effect of decreased mortality rates for successive cohorts” – in other words, if migrant parents inconveniently start living longer.)

In short, the commission thinks permanent parent visas are a thoroughly bad idea. To reduce the future burden of supporting more old migrants, it suggested the government dramatically increase the application charge for the contributory parent visa – “by roughly double in the first instance” – and simultaneously cut the annual intake. It suggested scrapping the non-contributory visa altogether, and instead introducing a strictly limited “compassionate parent visa.” This visa would only be available in a few compelling circumstances – if both parents of Australian citizen children were killed in a car crash, for instance, and the foreign grandparents were the most appropriate alternative carers.

Alone, such recommendations were not going to be politically palatable; they would enrage migrant communities lobbying to bring their parents to Australia. But the commission also sought to resolve the “tension between… the significant fiscal costs of this visa category and the desire to allow some parent and child reunion” by proposing a temporary but “longer-term” visa class, periodically renewable, which would allow parents to stay for longer than the maximum twelve months permitted under a visitor visa.

That’s the outline of the new visa now under discussion. In theory, it enables the government to reconcile the competing pressures identified by the Productivity Commission: the growing demand by migrant communities to bring parents to Australia, versus the associated public costs. As the discussion paper on the proposed visa puts it:

The Australian Government believes that parents should have the opportunity to visit children and grandchildren who live in Australia as long as parents and their sponsors can satisfy community expectations and that their stay in Australia does not have an undue cost impact on the Australian community.

This will be achieved by attempting to privatise all the costs of parent migrants under the guiding principle of “user pays.” In other words, temporary migrant parents will be required to have private health insurance and cover all their own medical bills, housing costs and living expenses. Sponsors – their Australian children – will be responsible “for ensuring that their parent does not become a burden on the Australian community.”

Sponsors’ capacity to meet this responsibility will be subject to threshold tests: an income assessment to show that they can support their parents, and a minimum number of years “living in and contributing to Australia” to ensure that they “have had sufficient time to become engaged with the Australian community and to contribute to Australia financially.” The longer a sponsor has been resident in Australia, the higher his or her priority for getting a visa for a parent living overseas. Sponsors will also be required to post a “significant” financial bond (immigration minister Peter Dutton has suggested between $5000 and $15,000), which government can use to recoup some costs in cases “where sponsorship obligations have not been honoured.”

But while drawing a boundary between temporary and permanent migration might appear bureaucratically neat, it won’t resolve all potential problems. As some of the questions posed in the immigration department’s discussion paper make apparent, things could get messy:

What (if any) limits should be placed on the total liability of sponsors where their parent incurs significant health or aged care costs not covered by their private health insurance?

In the event that the holder of a parent visa is unable to depart Australia due to illness or accident:

• what responsibility should be borne by the sponsor and their immediate family, and

• to what (if any) extent would it be reasonable for these costs to be borne by the Australian community?If a sponsor dies:

• in what circumstances, and what timeframe, should their parent be required to leave Australia

• what liability should remain with their immediate family, and

• in what circumstances should their immediate family be able to take over the sponsorship to enable the parent to remain in Australia?

It’s not hard to imagine difficult scenarios:

• A son-in-law sponsors his wife’s widowed mother to Australia but a few years later the marriage ends. The estranged husband withdraws his sponsorship and demands his bond back and the wife can’t step in because she has no independent income. The mother’s visa will be withdrawn, yet the distressed wife is in a vulnerable psychological condition, possibly suicidal, and she and her children need the support of her temporary migrant mother more than ever.

• After living in Australia for more than ten years on a temporary visa, an elderly parent develops Alzheimer’s. He claims he is being subject to elder abuse by his sponsor child. The relationship deteriorates to the point where the child withdraws sponsorship so the parent must leave Australia. But there is no one in the homeland to care for him. Does the father get sent back anyway? If not, who intervenes and who pays for the parent’s high-needs care?

These are not far-fetched possibilities. Human lives are messy and complicated and tend to explode administrative systems and rules, no matter how detailed and thoughtful. Cases like this will end up in the media and as lengthy, resource-intensive and tortuous appeals to immigration ministers to use their discretionary powers. The more people who use the visa, the more unforeseen circumstances and unintended consequences are likely to emerge. Such problems may be many years down the track, and so will land in the laps of future governments, but that’s no reason not to take them seriously today.

At this stage, though, the immigration department appears unable to offer even such basic information as an estimate of the expected demand for a new visa. We know from the length of the existing queues that there are at least 80,000 potential applicants, but the numbers are likely to be significantly higher once we factor in people who are put off by the current cost or the length of the wait, or who fail to meet the balance-of-family test. The discussion paper makes no mention of the potential number of future temporary migrant parents, and when I asked the department for data on how many people currently use work-arounds like the twelve-month subclass 600 tourist visa, I was told that the information was not “readily available.”

For those of us old enough to remember the non-alcoholic beverage Claytons – “the drink you have when you’re not having a drink” – the new temporary parent visa seems a lot like Claytons immigration. We allow people to live in Australia long-term – for five, ten, perhaps even fifteen or twenty years – but we never permit them to become Australian because of the costs they might impose on us. The requirement to leave for a month or two every five years is just a fig leaf to enable the deception: it means government can call migration temporary even when it is essentially permanent settlement, as with New Zealanders on special category visas, or refugees on temporary protection visas. The government can maintain the pretence that parents are just visiting, when in reality they are making their homes here.

The question of parent migration is undoubtedly difficult. All of us can understand the strong desire to keep fathers and mothers close by as they age, to have grandparents pass on cultural and familial knowledge to Australian-born kids, and to express our love for our parents in tangible, practical, intimate ways. Yet the Productivity Commission’s dry-eyed data is also compelling. As the commission argues, public funds spent supporting ageing migrant parents are funds that will be diverted from other areas of social policy. “Ultimately, every dollar spent on one social program must require either additional taxes (reduced private consumption) or forgone government expenditure in other areas … such as mental health, homelessness or, in the context of immigration, the support of immigrants through the Humanitarian Programme.”

A temporary parent visa might seem to offer a way out of this dilemma, but it risks creating a new cohort of people who are not quite Australian – who live in the nation for an extended period but have no say in the decisions that are made, no representation and no access to public support in times of need, and have restricted rights. To exclude long-term Australian residents from full membership of the political community in this way is inequitable and undemocratic, and age should make no difference to those fundamental principles. •