Dracula

By Bram Stoker | Penguin | $9.95

WHEN Bram Stoker’s vampire novel Dracula was first published it did not strike its readers as especially new or innovative. Despite its contemporary setting and some startlingly direct set-pieces – the description, for instance, of the asylum inmate Renfield ravenously consuming raw birds and afterwards disgorging their feathers retains its squirm-making power even today – the novel still seemed of a piece with the popular category of Gothic horror that stretched back into the eighteenth century. To the reader of 1897, busy dashing into modernity, Stoker was not so much reanimating, so to speak, the myth of reanimation – of corpses that could come to life to wreak havoc among the living – as recycling it. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla, for example, which set a clear precedent in the category of eponymous bloodsuckers, had appeared a good quarter of a century earlier.

Stoker’s novel seemed to hark back rather than forward, perpetuating a fictional form that like the vampire had lived beyond its allotted span. And Stoker did indeed owe much to the past. His vampire was an adaptation rather than an invention, derived not only from his literary predecessors but also from the Central European and other folkloric traditions that dwell with fascination on these frightening figures, whose modus operandi varied but who typically left as their calling card two subtly ominous bite marks in the softer regions of the neck, and who could be truly killed only by a stake driven, resolutely and without hesitation, straight through the heart.

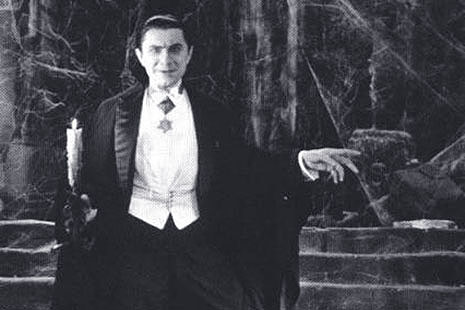

And yet with time Stoker’s creepy Count has come to seem not just another vampire in a long line of vampires and similar creatures of the night, but a true original, the first of his kind; a vampire for the modern world. In the years since Stoker first introduced the mysteriously ageless man with the pale skin and wispy hair, vampires and modernity have continued to keep pace with each other, developing in the process an increasingly complex and interdependent relationship. From the perspective of 2012 – the centenary, as it happens, of Bram Stoker’s death – we glimpse the figure of Count Dracula as it is refracted through the vast overlay of imitations, reinventions, homages and spin-offs that he has inspired.

For today’s readers, Dracula comes not at the end of the line but at the beginning, as the instigator of a never-ending chain of versions and sequels, in which the successive components are – like Stephenie Meyer’s “Twilight” novels, to take just one of many recent and spectacularly successful examples – themselves made up of self-generating sequels. It’s a population explosion of the UnDead. And it is with the Un-Dead – the creatures who, once bitten, become vampires themselves, hovering forever between life and death – that Stoker so accurately caught the spirit of modernity and its problematic relationship between progress and tradition. Dracula’s bite condemns the victim to be, like Dracula himself, marooned for eternity between the competing calls of the future and the past.

The characters in Stoker’s novel who, under the direction of Professor van Helsing, “one of the most advanced scientists of his day,” challenge the vampire and eventually defeat him – the young solicitor Jonathan Harker, his devoted wife Mina, Professor van Helsing’s former pupil Dr John Seward, together with Seward’s boon companions, Quincey Morris and Lord Godalming – are all children of the newly emerging technological age, determinedly up with the latest, committed to logic and rationality and scientific method. By deploying a narrative form that combines the direct or indirect commentary of all of these characters, Stoker depicts a world of continuous technological invention and improvement. Mina composes her journal entries and transcribes Jonathan’s shorthand notes on her typewriter, which travels with her everywhere. Jonathan, in addition to writing everything down, also takes pictures with his Kodak. Dr Seward dictates his thoughts into a phonograph. Recording is a way of coping with the ever-changing world, of rendering it logical and manageable and under control, even as this new world surges forward at a pace that makes it difficult to keep up.

Yet for all the efforts made by Stoker’s cast of vampire hunters to document and record and understand what they are up against, the unmanageable has a way of defying rational explanation. In the long first section of the novel, in which Jonathan travels on business to Transylvania at the request of Count Dracula only to find himself made a prisoner in the Count’s castle, the young man comments self-mockingly on his own shorthand skills (Pitman’s system of shorthand made its first appearance in 1837) as being “nineteenth century up-to-date with a vengeance.” But being up-to-date is no protection against unexplained influences from the past. “Unless my senses deceive me,” muses Jonathan, “the old centuries had, and have, powers of their own which mere ‘modernity’ cannot kill.” On the one hand technology and human inventiveness seem to hold out the prospect of a brighter future; on the other, “we seem to be drifting to some terrible doom.”

It is this fascination with ambiguity and contradictoriness and the borderlands between ostensibly definable states – not only between the past and the future, but between death and life, instinct and reason, masculinity and femininity, tradition and innovation, hope and despair – that makes Dracula, despite the many characteristics that identified it as old-fashioned when it first appeared more than a century ago, a truly modern novel. When the good guys can say of the unfortunate Lucy Westenra, who has been lured by Dracula into joining the ranks of the Un-Dead, that not only must they drive a stake through her body in order to save her soul, but also “cut off her head and fill her mouth with garlic,” we know we are in the midst of a morally unsettling and contradictory universe.

This latest edition of Dracula appears as one of 100 classic works of fiction in the new Penguin English Library, a series that first appeared in the sixties and has now been reworked for the twenty-first century. With strikingly-designed covers by Coralie Bickford-Smith, employing repeat motifs that allude strongly to wallpaper (“So, which cover have you settled on for your digital wallpapers and backgrounds?” asks the English Library Twitter feed), and block-coloured spines that stacked together have the look of a Bridget Riley painting, the series makes a claim for the virtues of reading – and possessing – the physical, aesthetically pleasing object rather than the digital download. As Bickford-Smith suggests in a recent interview, the rise of new technologies can stimulate the old technologies to do better, which is partly what accounts for the massive revitalisation of book design in recent years. “If it’s cheaper and more convenient to read a novel on your phone,” says Bickford-Smith, “then books have to justify their presence and expense by accentuating the qualities of the physical object.” They do so, you might say, by demonstrating “powers of their own which mere ‘modernity’ cannot kill.” •