White Noise

By Don DeLillo | Picador | $22.99

TO MARK the fortieth anniversary of its founding in 1972, Picador has reissued a set of its twelve most popular and prize-winning fiction titles. Among the twelve are Bret Easton Ellis’s controversial American Psycho (1991) – still sold in shrink-wrap in this country – Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones (2002) and, as a welcome Australian inclusion, Tim Winton’s Dirt Music (2001). Most of the novels selected for this international dozen made their first appearance relatively recently, and some could even be described as new – Mother’s Milk by Edward St Aubyn from 2007, Room by Emma Donoghue from 2010.

A few of the dozen do date from nearer to the beginning, when Picador launched its strikingly designed paperback editions onto the market. Picadors were not, typically, lined up in bookshops with all the others, in long rows of standard shelves, spines stoically facing forward. Instead their bright, in-your-face covers would appear full-frontal, on one of those wire-and-plastic versions of the traditional revolving bookcase. As often as not the display stand would be plonked down in a high traffic section of the bookshop, making it a more attractive proposition to stop and browse than to try to struggle past.

Something about the look of a Picador paperback made it seem very much of the moment. In many cases, that cutting-edge quality, whether of the cover artwork or the contents or both, has lasted amazingly well. It is even tempting to think that the really outstanding novels among them, the ones that were destined to be regarded as modern classics, managed somehow to instil an extra level of inspiration when it came to designing the cover.

Such was certainly the case with Don DeLillo’s White Noise, another of the festive dozen and arguably the most lauded and influential of them all. First published in 1985, when it won the US National Book Award, White Noise became almost immediately – and has remained ever since – the defining text of postmodernism, with its endless play on notions of originality and imitation, of the trivial and the serious, the innocent and the knowing. The genesis of that original cover (shown right) is recalled in a brief collection of notes and snippets about the publication history of White Noise that appears at the end of this new edition. The design deployed video images, computer graphics, photography and typography in a kind of overload of new technology and mixed media. The illustrator, Russell Mills, based the final design on “monochromes using car spray paints” that had been specially commissioned, in a nice postmodernist touch, from the rock musician and video artist Brian Eno.

DeLillo has described White Noise as “an aimless shuffle towards a high intensity event,” the occasion being a toxic spill that forces the inhabitants of a Midwestern town to evacuate their homes. DeLillo’s “aimless shuffle,” which is of course anything but aimless, covers an extraordinary variety of ground. We follow Jack Gladney – a professor in the new field of Hitler Studies – and his wife, ex-wives, children, stepchildren, friends and colleagues, as they face the big issues – principally the prospect of death – in a world where nothing is original, where “everything was on television last night,” where people act out the events of their lives according to the standard plots – what would now be called the story arcs – of movies. And it is on this question of imitation – the idea that everything is a simulacrum of something else, and that no matter how hard you look you will never locate the original because it is unlocatable – that White Noise has suffered, ironically enough, from an excess of imitation.

One frequently quoted passage centres on “the most photographed barn in America.” Waves of tourists and pilgrims come to the site with their cameras, not because it represents events of historical or social significance, but because it has been repeatedly photographed. It is famous because it is famous. “No one sees the barn,” says Jack’s friend Murray. This idea, that the barn has no substance of its own, that it exists only in photographs and images which themselves can be endlessly manipulated, has become so embedded in our cultural mindset that it is difficult today to feel the full force of DeLillo’s metaphor.

In most other respects, though, White Noise continues to strike an impressively prescient note. DeLillo is brilliant on the unthinking habits of daily life, the ways in which we continue to behave in primitive, herd-like ways, without ever quite cottoning on to just how the system is supposed to work. We suffer from a surfeit of inventiveness, which promises to make our lives easier and more rewarding, but often just makes everything more confusing than it already is. Jack describes a visit to the supermarket, where the produce bins “were arranged diagonally and backed by mirrors that people accidentally punched when reaching for fruit in the upper rows.” And in a vignette that seems to collect all the feelings of incipient despair that can be drawn out by a simple trip to the shops, Jack zeroes in on the way that “people tore filmy bags off racks and tried to figure out which end opened,” a behavioural tic that is as characteristic of supermarket shopping today as it was in 1985, and may finally disappear only with much heralded legislation against the use of plastic bags.

DeLillo catches in their developmental stages those aspects of the social landscape that have come to dominate it – the rise of the internet, the decline of privacy, the re-emergence of religion as a driving political force. He is especially good on the widening gap between intention and outcome – he has fun, for example, with the psychic Adele T., who is sometimes called in by the local police to help with difficult cases. Adele has a poor track record, except when it comes to locating things – bodies, the stashed proceeds of robberies – that the police haven’t actually been looking for.

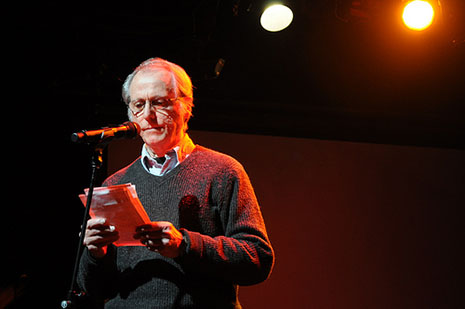

In several recent interviews, DeLillo has raised the possibility of the end of narrative altogether – the end of one thing leading to another. Instead of responding to narratives and stories that originate outside ourselves, we will each of us be able to create our own. “An individual will not only tap a button that gives him a novel designed to his particular tastes, needs, and moods, but he’ll also be able to design his own novel, very possibly with him as main character.”

A hint of that labile future is contained in the cover design (right) for this latest re-issue of White Noise. In common with the other titles in the set, it is starkly black and white, with both image and typeface reinforcing a distinctly retro look while also being aggressively up to date. A television screen contains a human silhouette, partly obscured by interference, or “white noise.” The chief designer for Picador, Neil Lang, explains on the company blog how it was important to produce something that would work well online. To this end, the cover was also created as a gif animation, a kind of simplified moving image. Click on the link and the bands of interference on the television screen move up and down. What’s that about? Lang is not quite sure, other than to explain it as an attempt to “just create interest and maybe get people talking.” What the gif really means, for the changing relationship between print and the moving image and for the very future of the novel, will almost certainly be clearer by the time of the next re-issue of White Noise. •