The story is familiar enough. An opposition leader seeks to modernise his party by transcending the old ideological opposition between state schools and church schools. Above all, he wants to woo the Catholic vote needed to win government. Prevailing over his rivals, he jettisons the party’s century-old opposition to public funding of private schools.Then, on winning government, he initiates a process of consultation, negotiation and policy formulation that culminates in a widely hailed breakthrough. Those years in power, from 1972 to 1975, come to be seen as a turning point that still defines the education landscape.

Gough Whitlam’s Australia? Yes, but also Norman Kirk’s New Zealand. That’s where the likeness ends, though, for the new educational epoch Kirk ushered in was quite different from the era created by Whitlam and his education adviser Peter Karmel. In Australia, church schools got what we called state aid, but they remained distinct from the state school system. In New Zealand, church schools became state schools, creating a single system of schools, some religious, most secular. It was “perhaps the most important educational measure passed by parliament in the twentieth century,” says Sir Patrick Lynch, chief executive of the New Zealand Catholic Education Office for more than two decades.

New Zealand’s parliament passed the Private Schools Conditional Integration Act in October 1975. Like its Australian counterpart, Kirk’s Labour government fell just weeks later (though in much more conventional fashion). But the Integration Act came into force the following year, and by the end of 1984 every Catholic school in the country had become part of the state system. Today, 13 per cent of New Zealand’s schools are “state integrated” in this way. They are mostly Catholic, but also include Anglican, Nonconformist, Muslim, Jewish, Steiner and Montessori schools. Non-integrated private schools constitute just 3 per cent of New Zealand’s education sector.

The essence of the NZ compromise was that schools would be state-funded and state-run but would retain their religious ethos (or “special character”). Schools that integrated into the state system would continue providing religious education and services according to their own lights. An exemption to anti-discrimination legislation allowed them to favour co-religionists in employment decisions, and all but 5 to 10 per cent of enrolled students would come from among the faithful.

The proprietor of the newly integrated school – typically the Catholic Church – retained ownership of its (often substandard) buildings, was responsible for their maintenance, and was obliged, where necessary, to make improvements to ensure they met basic requirements. Because of these obligations, and because many of them entered the government system carrying significant debt, Catholic schools were permitted to charge “attendance dues.” But they could be used only for those circumscribed purposes, and only after the government had signed off on the quantum. Integrated schools were also subject to a “maximum roll,” a cap on enrolments designed to prevent state-funded schools from cannibalising each other. In other words, the systems on either side of the Tasman became very different indeed.

Before all this happened, New Zealand and Australian schooling had run on parallel tracks. The Australian colonies established public schools between 1851 and 1894, withdrawing funding from church schools at the same time. New Zealand created its system of free, secular and universal public education in 1877. Despite this, Catholics in both countries were determined to provide a church-run school in every parish, largely courtesy of the nuns and priests who worked as teachers for next to nothing.

In both countries, the economics of Catholic education began slowly imploding after the second world war in the face of a perfect storm: the baby boom, the extension of compulsory education, and growing demands for better facilities and smaller classes. Above all, the decline of the religious vocation meant that Catholic authorities were forced to hire teachers from outside their own ranks – teachers unwilling to wait until the next life for their just rewards. “The proportion of lay teachers in the Catholic system grew from 5 per cent in 1956 to 38 per cent in 1972 with resulting increases in salary costs,” Lynch writes of New Zealand’s experience. “By the end of the 1960s a looming financial crisis had brought the possibility of a total collapse of the system.”

Conservative governments in both countries were the first responders. In Australia, Menzies exploited the controversy sparked by a “strike” in Catholic schools in the NSW town of Goulburn by announcing state funding of science blocks. In New Zealand, the 1964 Education Act gave the minister discretion, for the first time, to make grants to private schools.

If state aid itself wasn’t a sufficiently seismic shift, then came the additional element of Labor/Labour support. Norman Kirk became opposition leader in December 1965, just over a year before Gough Whitlam replaced Labor leader Arthur Calwell. Like Whitlam, Kirk was determined to match the conservatives on state aid, if not outdo them. In the lead-up to the 1969 election, Kirk announced that a NZ Labour government would pay no less than half the salaries of teachers at private schools. Labour’s support for state aid could no longer be doubted. Like Whitlam, New Zealand’s modernising leader lost that year but retained the leadership, and his commitment to public assistance for church schools.

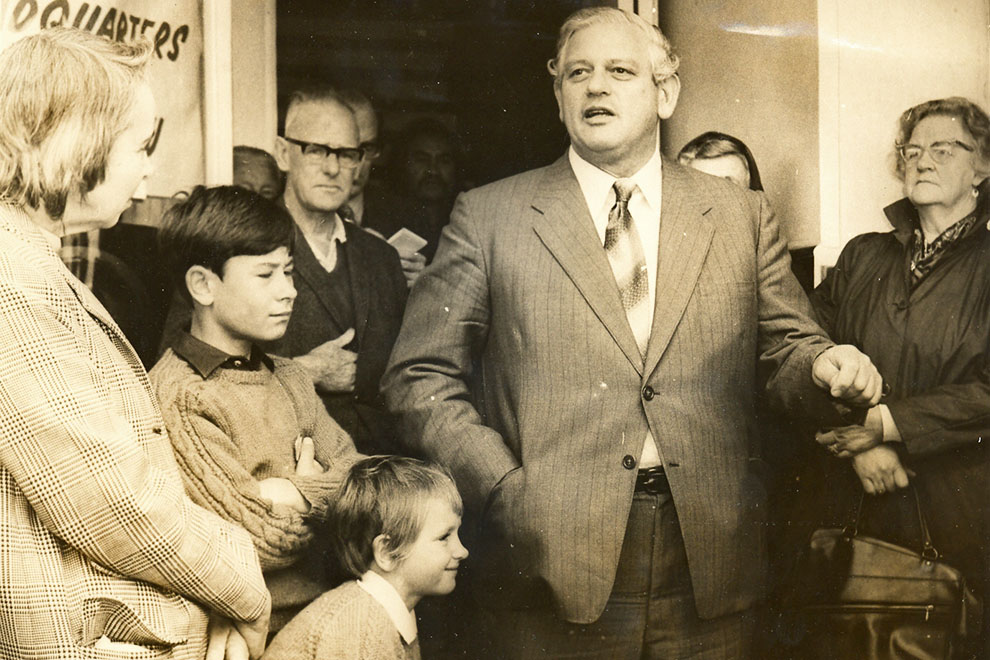

The integrator: Norman Kirk outside the Labour Party’s headquarters not long before the November 1972 NZ election. Horowhenua Historical Society Inc.

By the late 1960s, New Zealand’s Catholic system was on the verge of bankruptcy. The situation was hardly less acute in Australia. As George Pell recalled in 2007, “My first cousin, a Josephite nun, like many others once had to teach a primary class of over ninety children, some of them with English only as an imperfect second language. This was unsustainable. Without government money many Catholic schools would have been forced to close.”

And yet, for all the similarities between the two countries, profound differences shaped policy-making. Some were historical, like the split in the Australian Labor Party and the emergence of the Catholic-dominated Democratic Labor Party, which intensified the state aid debate. Others endure today. Catholics make up about a quarter of Australia’s population but less than a sixth of New Zealand’s. And getting things done can be easier in New Zealand’s unitary system of government. Just ask Julia Gillard about the task of persuading every Australian state government and state Catholic system to get on board for a big change.

Kirk and Whitlam faced the same problem: the Catholics couldn’t finance their own schools any longer but were as determined as ever that they remain open. But they encountered this problem in very different contexts. As a result, Whitlam’s 1969 election manifesto announced a neutral body, a Schools Commission, that would allocate funding according to a neutral criterion, need. Kirk’s equivalent policy document, A Fair and Just Solution, included for the first time a reference to a bolder idea: “integration.”

Rory Sweetman’s fascinating history of this bold idea takes its name from Kirk’s policy (with only the addition of a question mark). Sweetman describes how the idea of integration was germinated inside the education policy committee of the Labour Party. In the policy’s initial iteration, cooked up by two state school teachers-turned-MPs, Jonathan Hunt and Bob Tizard, private school “buildings would be ceded to the state” and “religious instruction would be given only outside school hours.” Funding to schools that chose not to integrate “would be progressively reduced over five years until no aid was received.”

The political hardheads inside the Labour Party wanted to woo the Catholic vote, not antagonise it. Accordingly, the Hunt–Tizard integration scheme was largely shelved. But the word stuck (and its place in Kirk’s policy manifesto went some way to mollifying his opponents, still reeling from Kirk’s election promise to pay at least 50 per cent of private school salaries). Kirk, Sweetman comments, “was assisted by the vagueness of the term.” Until a post-election conference actually convened, “integration was whatever the Labour leader said it was.”

When Labour finally came to power in December 1972, the conference had to be held and the word had to be defined. The conference took place in May 1973, the same month that, in Australia, Peter Karmel handed down his report on needs-based funding. The conference gave birth to a working party (with representation from the Catholics, the teacher unions and the education ministry) that toiled away for nearly two years. It didn’t hurt, according to Sweetman, that many of the negotiators on the working party shared experience serving in the war. “They didn’t have the entrenched suspicion and grievance and animosity that had been inherited from the previous generation,” he told me. “They had a lot more in common than they opposed.” The scheme ultimately hashed out by the working party formed the basis of the Integration Act and thus of New Zealand’s education system today.

If necessity was the mother of the Catholic commitment to integration, the courage and imagination of the church leadership shouldn’t be discounted. Perhaps the best illustration of their commitment to the ideals of integration was their refusal to walk away from the scheme when they could. Sweetman told me that “when the Conservative government got into power under Muldoon in [December] 1975, they basically said to the Catholic bishops, ‘Look, you don’t really need this integration – we’ll give you more and more state aid.’” The bishops stood by the deal and the Muldoon government duly implemented it.

New Zealand’s two major teacher unions, the New Zealand Education Institute, or NZEI, and the Post-Primary Teachers’ Association, had become advocates of integration, and were represented on the working party. The two unions had fought each and every increase in state aid during the 1960s, but when Labour joined the National Party in embracing state aid, they were clear-sighted about the consequences. In the wake of Kirk’s September 1969 state aid announcement, NZEI national secretary Ted Simmonds reflected that “there is now no political party with the will to restrain the flow of state money. Each party can now be expected to offer even more attractive propositions to the voters.” It was an unshrouded recognition that the state aid debate – as it had played out since free, secular and universal public education had been introduced almost a century before – was over.

In essence, New Zealand’s teacher unions decided to grasp one horn of a dilemma. They could insist that public schooling must be secular, and by corollary, that religious schools raise revenue, in part or whole, through charging fees. This would entail a continuation of what looked like an increasingly futile battle against state aid. Or they could cede the secular ground and attempt to shore up the free and universal nature of publicly funded schools.

“The integration of a private school is a costly exercise,” Simmonds conceded fifteen years later, “but with integration there is a measure of control. It could be argued that without the Integration Act, the money would still have been spent on the private schools, which would have remained completely independent. Without integration there would certainly have been a separate state-supported private school system.”

Meanwhile, Simmonds’s counterfactual had been playing out in Australia. “It wasn’t so much that the New Zealand system was attractive,” says Robert Bluer, who became secretary of the Australian Teachers’ Federation in 1982, “it was that the Australian system was becoming more and more unattractive. The process of funding from the Commonwealth to non-government schools was accelerating very quickly. People were fairly desperate to find a way through it.” Bluer was part of a Teachers’ Federation working group established in 1981 to consider the question of religious public schools. A delegation visited New Zealand to study the emerging results from its experiment in integration and developed a draft policy supporting “universal public education.”

That policy was put to the 1982 conference of the Teachers’ Federation. Arguably, it was ten years late – though, as we’ll see, it was much too early for some. The analysis was much like that of Simmonds in New Zealand a decade earlier. “It was a situation where simply opposing the funding for non-government schools seemed to be a complete waste of time,” says Bluer. According to his ally at the Victorian Secondary Teachers’ Association, Graham Marshall, the proposal “had the political advantage of bringing the Catholics into some sort of accommodation with the public system and stopping them lining up with the Independents [the major non-denominational private schools].”

Speaking at the Teachers’ Federation conference was the president of New Zealand’s Post-Primary Teachers’ Association, Des Hinch (Derryn’s brother, as it happens). By this point, both of New Zealand’s teacher unions had disowned the integration system they had helped to create. This was in no small part due to a group of dissidents, known as the Committee for the Defence of Secular Education, or CDSE, which had broken away before the Integration Act was passed. The dissidents championed an interpretation of events in which the Catholics had scored an outright victory. “After years of studying the Integration Act and its implementation,” wrote their leader Jack Mulheron, “I can find no concessions of any substance whatsoever made by the Catholic authorities.”

The CDSE didn’t manage to stem the tide of integration, but it did influence the unions’ thinking. At the Teachers’ Federation conference, as Graham Marshall recalls it, “what Hinch did was – like his brother – simply threw a big, stinking bomb in the middle by saying it was a terrible deal and basically the Catholics got everything they wanted in this integrated system and they didn’t have to give up anything.”

That intervention didn’t help, but it might not have been decisive. Even before the Perth conference it had become clear that some of the most powerful state unions were reluctant to abandon their traditional posture. And, as it turned out, the conference didn’t just reject universal public education, it passed an amendment reaffirming total opposition to all state aid. Thirty-five years later, Bluer describes it as “a complete lunatic position which got us nowhere.”

At the following year’s conference, the Federation – which was not an affiliate of the Labor Party – determined to actively support the party at the 1983 federal election. Labor, it need hardly be said, was not about to abolish state aid. Another Federation delegation visited New Zealand in 1990; although it considered the integration question, it was more focused on other matters. The Federation maintained its policy of opposition to all state aid to church schools. A discussion paper published a couple of years later by what had become the Australian Teachers’ Union (now the Australian Education Union) noted bluntly that “our policy is gaining no headway and few outside the ATU even want to listen to the arguments. In fact, any attempt to propagate the policy reduces the credibility of the ATU in all areas, even those beyond the funding issue.”

If blanket opposition to state aid in Australia was an abject failure, it can’t be said that the embrace of integration in New Zealand has been an unmitigated success. We might expect that integrated and traditional state schools would share equally in the responsibility of educating disadvantaged students. But that turns out not to be the case. New Zealand categorises schools into deciles that “indicate the extent [to which] the school draws their students from low socioeconomic communities.” Only 20.7 per cent of state-integrated schools are found in the bottom three deciles, but 33.7 per cent of state schools are.

The first problem is attendance dues. The Integration Act specified that these could not be used “to provide or improve the school buildings and associated facilities to a standard higher than that approved from time to time by the secretary [of the education ministry] as appropriate for a comparable state school.” What this means is that attendance dues at Catholic schools today are $300–$400 a year at primary level, $600–$800 at secondary schools.

But the story is different at Wanganui Collegiate School, one of New Zealand’s most exclusive private schools, which applied to integrate into the state system after running into financial difficulties. Today, the school enjoys the recurrent public funding that comes with integration, and yet its attendance dues are $2400 a year. Wanganui is not alone, either. Elim Christian College charges $2175 a year, and dues at Lindisfarne College Hastings are $1600. We’ll see how they justify that in a moment.

Compounding the attendance-dues loophole is the issue of “voluntary” donations. As a principal at a state-integrated Catholic school wrote in a letter to the education minister in 2009, “I work in a Catholic school and our fees are less than $1000 all up – $665 attendance dues and a real DONATION (not a phoney one) of $300 – total = $965. It is hard to compete with schools for whom the attendance dues and donation total anywhere between $4000–$6000 and more as they have an ability to service debts and build illustrious pavilions/performing arts suites etc.”

On top of enduring financial barriers to entry, critics argue that state-integrated schools have retained at least some of their power to pick and choose their clientele. “The original special character requirements have been so watered down over time that they now appear little different from a public school mission statement,” a Post-Primary Teachers’ Association position paper claimed. “When no particular religious denomination is required… the school may simply select its students on the basis of parental wealth.” The CDSE’s Jack Mulheron argued that the maximum rolls, intended to ensure all publicly funded schools functioned as a cohesive network, turned out to be worthless. “Integrated schools cheerfully ignored the agreements and enrolled pupils in excess of the maximum,” he claimed.

But if New Zealand’s model is far from perfect, it is also far superior to Australia’s. The case of Wanganui Collegiate illustrates this well. Wanganui’s attendance dues, the common defence goes, have to be approved by the education ministry – just like those of every state-integrated school. A ministry spokesperson offered the following justification: “Wanganui Collegiate currently has relatively high attendance dues because it is newly integrated and has high levels of debt servicing due to capital expenditure required to bring buildings up to an equivalent state standard. Over time, as debt servicing costs decline, attendance dues levels should also decline at the school.” No doubt Wanganui has much debt to service, but the idea that it reflects the expenditure required to bring buildings up to “a comparable state school” standard is hard to square with the virtual tour provided on the school’s website.

The specific adjudication may be unconvincing. But the fact that there is an adjudication at all reflects the shared agreement that government has a right to control the fees of the schools it funds. It is taken for granted that state-integrated schools must demonstrate a case for the fees they charge using precisely articulated criteria.

As with fees, debate in New Zealand about enrolment practices concerns the strength of regulations and the thoroughness of their application. Such regulation is non-existent in Australia, and lies outside the shared premises of political discourse. Surveying the Australian scene, Sweetman comments that “it is surprising that the CDSE did not ask whether integration had saved New Zealand’s state school system from a worse fate.” As the current president of the NZ Post-Primary Teachers’ Association, Angela Roberts, said to me, “We wouldn’t want to be where you guys are, that’s for sure.”

The possibility of an integration-type model clawing its way onto Australia’s bitterly contested education policy agenda seems remote. Integration happened in New Zealand when the Catholic education system, close to bankruptcy, was open to discussing the terms and conditions on which the public purse might be opened. The equivalent moment in Australia was complicated by internal Labor Party politics and passed with the Karmel/Whitlam settlement. Today, Australia’s Catholic schools are not under any visible financial strain and there is tripartisan support for the very extensive government support they enjoy. Even erstwhile enemies of state aid have thrown their energy into a reform under which “no school loses a dollar.” Public money flows to church schools without obstacle or challenge.

And yet, so much has changed since the days when Catholic classrooms teemed with ninety children and the authorities couldn’t afford new toilet blocks. In their latest analysis of My School data, Chris Bonnor and Bernie Shepherd show that 93 per cent of Catholic schools have an “index of community socio-educational advantage” of between 950 and 1150. These schools receive “between 90.8 per cent and 99.5 per cent of the public dollars going to similar public schools.” Independent schools aren’t far behind: “they receive between 79.5 per cent and 94.6 per cent of what goes to similar public schools.” Bonnor and Shepherd aren’t talking about total funding from all sources. They’re referring to government funding alone. (In New Zealand, by contrast, private school students are currently funded by the government at levels of between one-sixth and one-third of their state and state-integrated counterparts.)

This fundamentally changes the equation. First, the additional government spend necessary for an integration-type model has fallen dramatically. Bonnor and Shepherd estimate that in 2014 it would have required governments to contribute an additional $1.9 billion (or 4.5 per cent of total recurrent government expenditure on schools) to fund non-government schools to the same level as similar government schools.

Two billion dollars is still a lot of money. And the lesson from New Zealand is that attendance dues have allowed the essential idea of integration to be corrupted. If you’re going to do it, government should pay for infrastructure as well – and that’s going to cost. Treasuries would resist handing the money over; public educators would grimace at whom it was being handed over to. But it’s a much smaller pot of money than it once would have been, and the pot gets even smaller when the accounting becomes more comprehensive. For instance, as Peter Martin reported in the Age, the GST exemption on private education cost the budget $4.5 billion this year.

The equation has changed for Catholic education too. As George Pell, then archbishop of Sydney, told the National Catholic Education Conference in 2006, “Catholic schools are not educating most of our poor.” On the contrary, he told his audience; 69 per cent of students from the poorest third of Catholic families attended public schools. That made poor Catholics almost two-and-a-half times more likely to attend public schools than their more privileged co-religionists. Only 21 per cent of poor Catholic kids attended Catholic schools.

As Dean Ashenden wrote recently in Inside Story, “a school system established to help the poor and the excluded has off-loaded much of that task to the government schools in favour of catering to those already in the mainstream.” Pell expressed the point differently: “Predominantly our schools now cater for the huge Australian middle class, which they helped create.” The cardinal’s is a more positive spin but he appears to be cognisant of essentially the same truth. And the challenge is not simply that Catholic schools exclude the poor but that a growing proportion of enrolees, more than one in five, aren’t even Catholic. If these schools face an existential threat today, it isn’t deregistration or overwhelming disadvantage but the dissolution of their essential character.

Most consequentially, it would now be a relatively small step for true believers in public education to accept that some public schools might have a religious ethos. Secularism may be an article of faith but public funding of religious schools is a fact (a fact that nobody is seriously trying to change). To be sure, when Ted Simmonds threw his support behind integration in New Zealand in the late 1960s, it was based on a hunch. His view – that with or without integration public funding to religious schools would continue to escalate anyway – had much going for it. But it was conjecture; contestable, possibly even alterable.

By the time of the 1982 Australian Teachers’ Federation debate, the insistence that the tide of state aid could be stopped was less credible. But the future was still unknown. Today, questions of principle evaporate in the face of an inescapable reality; publicly funded religious schools exist and they’re here to stay.

To accept that parents have the right to choose a religious school for their child within the public education system would alter the way we have thought and talked about schools for well over a century. Ever since it was decided that public education would be secular, we have taken it for granted that religious schools would be private. This assumption has been so deeply embedded that even when “private” schools became mostly publicly funded we continued to insist on using the misnomer.

Because we continue to insist that religious schools are “private,” we allow them to exempt themselves from the obligations associated with public schools. To deal with some of the effects of this distinction, the Gonski Review recommended that we should allocate more funding to schools where disadvantaged students are concentrated, regardless of whether they are public or “private.” But Gonski neither suggested (nor, it would appear, seriously considered) that publicly funded religious schools should be as accessible to disadvantaged students as publicly funded secular schools are.

Two logically distinct ideas have become historically entangled. The first is that public funding should entail public obligations as determined by the public’s agent, the government. The second, logically unrelated idea is that public education cannot accommodate a plurality of views about what role, if any, religion should have in education. Some careful disentangling could isolate what is really at stake and engender a more cooperative mood at the same time. If such a task were contemplated, the courage and imagination – and the mistakes – of the architects of New Zealand’s experiment in integration may be a good place to start. •