It was in a Melbourne museum that I realised I didn’t know the traditional name for the area in South Australia where I’d grown up. I was leaning over a large map of Victoria carved into wood and displayed on a low table. The boundaries of the state’s thirty-eight Aboriginal language groups were marked out. Within each one was a button. Touch it and a voice pronounced the name.

I worked my way around the map, tapping each button. Then I zeroed in on the Melbourne area, where there are five language groups: Woiwurrung, Boonwurrung, Wathaurong, Taungurung and Dja Dja Wurrung. I’d tap one, listen, say the name under my breath, tap it again, listen, say the name again, move onto the next one, do the same, over and over.

I love words, not just the look of them and the work they do, but the sounds they make. These words had a rhythm all their own. They set up a music in me that stayed as I wandered around the rest of the museum, learning about Victoria’s First Peoples, their relationship to the land, and their stories of the creator and protector spirits, Bunjil the eagle and Waa the crow. By the end of the afternoon, I knew more about the deeper story of this place I’d lived in for just five years than I did about the place that first formed me.

I was born in Clare, a small town two hours’ drive north of Adelaide. For seventeen years, through the 1960s and 70s, my world was family, that town of three thousand, and the bush and farms and vineyards around us. Mostly we were descendants of Irish, English and Scottish immigrants, with a few Italian, Greek and Polish families in the mix. My own ancestors on both sides were Irish, and had settled near this same area in the 1840s.

At my primary school I wasn’t taught anything about Australia’s First Peoples. At high school, the history subjects on offer were modern European and classical studies, and an Australian history subject that in hindsight could have been called “Australia Since 1788.”

After I finished school, I left Clare and lived in Adelaide for a few years, travelled overseas for a while, then settled in Tasmania in the late 1980s. I’d become interested in Australia’s colonial history and was reading about it a lot. Occasionally I went to talks by local academics and Aboriginal people.

I moved to Melbourne in 2008, during the week of the national apology to the Stolen Generations. Soon I was learning about the Wurundjeri people, and bit by bit I came to understand about the different language groups making up the larger Kulin nation. I started reading up on local history, getting to know important sites and dates in Melbourne for Aboriginal people, going to Tanderrum ceremonies, and seeing plays about places like Coranderrk. It made me feel both more connected to Melbourne and more uncomfortable about what I was hearing and what it all meant.

All through the years, I went back to Clare regularly to see family and friends. But I was oblivious to the history of the people who’d lived there for tens of thousands of years before – I didn’t know their name, culture, language, anything.

From the internet, I’d learnt that the original people were the Ngadjuri, a word in their language that means “we people.” I had no idea how to pronounce it. Each time I tried, I’d stumble over it, mumble “nud-jury,” then “naa-joorey,” then shake my head and give up. I felt stupid and awkward.

Several years ago, on a regular trip back, I decided to stay on longer and start finding out what I could.

Clare’s main street as you come in from Adelaide is as familiar to me as my own hand. The oval, the bridge over the creek, the old two-storey banks, the fish-and-chip shop where I earned pocket money and, halfway along the main street, the two-storey town hall that houses the local history centre.

I walk into the foyer and up the wide staircase, my hands on the smooth, varnished wooden banister I remember sliding down as a child. The room is huge, with high ceilings, tall bookshelves and a massive wooden table. Along a wall and tucked into corners are old grey filing cabinets, computers, a heavy-duty photocopier. The volunteer on duty is the mother of a boy I was at school with, and after a quick catch-up I tell her what I’m after. She finds me a book and some folders, settles me at the big table and leaves me to it.

The book is Ngadjuri: Aboriginal People of the Mid North Region of South Australia. On the front is a painting, by renowned contemporary artist Robert Hannaford, of a group of pre-colonial Aboriginal men walking through a stand of gum trees. Alongside it is an old sepia photograph of an Aboriginal man dressed in a light-coloured three-piece suit, his hair white, a slight smile on his face.

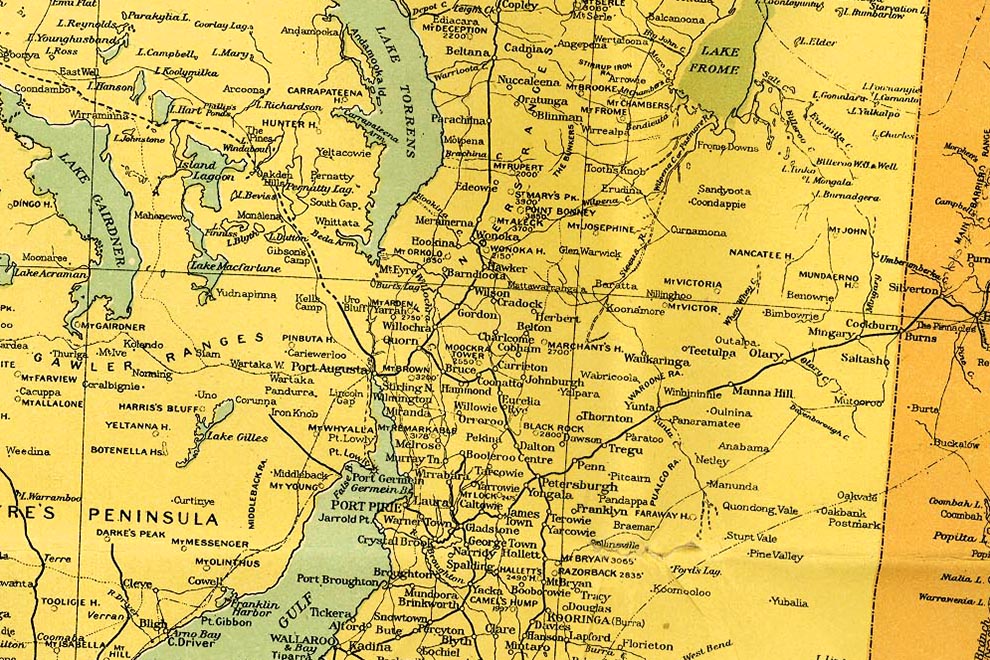

On the back cover is a map of the mid north of South Australia, marking out Ngadjuri country as it was documented by anthropologist Norman Tindale in 1974 – a roughly rectangular area extending from Gawler in the south to the lower Flinders Ranges in the north.

Starting from the top, I trace my finger over the map, silently sounding the names of the towns. Bimbowrie, Waukaringa, Minburra, Moockra, Coomooroo, Orroroo, Paratoo, Oodlawirra, Nantabibbie, Pekina, Tarcowie, Yongala, Appila, Mannanarie, Belalie, Gumbowie, Terowie, Caltowie, Canowie, Yarcowie, Ulooloo, Bundaleer, Booborowie, Manoora.

All are familiar to me. When we were children, my dad took us for drives up north to visit relatives, and he’d often recite the names of the towns, arranging their order to make them rhyme and sound a rhythm: Oodlawirra, Nantabibbie, Orroroo, Paratoo. On he’d go, his eyes twinkling. All these years later, I instantly remember the rhythm, nodding my head to the beat of it.

I slide my finger down the shiny paper and pause at my home town, and a cluster of other names I know well but which sound so different from the others – Clare, Sevenhill, Penwortham, Watervale, Leasingham, Auburn, Riverton. It’s abrupt, the shift. In time, I’ll come to understand more about why.

The Ngadjuri book was published as a teaching resource for South Australian schools in 2005. Writing it took a decade of work by many, among them Ngadjuri people, schoolteachers, curriculum staff, archaeologists and historians. The book’s genesis lay in two sources: research by Ngadjuri man Fred Warrior and archaeologist Sue Anderson, and a booklet produced in 1995 by Fran Knight, a teacher in the mid-north town of Peterborough, who had spent years researching Ngadjuri history and culture so she could teach it to her students. Printed on high-quality gloss paper, many of the 150 pages feature colourful photos and illustrations, and at the end of each chapter are activities for teachers to use in the classroom. The content covers Ngadjuri country, language, Dreaming, traditional life, archaeology, the arrival of Europeans, resistance to invasion in the 1840s, dispossession of the land through to the 1900s, and a final chapter on shared history and the future.

I flick through the whole book, then return to the section on language. From a sidebar I learn that Ngadjuri words that end in -owie mean fresh water. Caltowie, where my cousins grew up on a farm, is “waterhole of the sleepy lizards”; Booborowie, where I played netball, is “round waterhole”; Yarcowie is “wide water.”

Too soon, it’s time for the history room to close, so I take down the book’s details and later, back home in Melbourne, order my own copy. The day it arrives, I settle at the kitchen table with a coffee and once again head straight to the chapter on language.

Over 300 words are listed, first from English to Ngadjuri and then from Ngadjuri to English, along with instructions on how to pronounce them. I sit, like a kid again, in my classroom of one, slowly, methodically, following the invisible teacher.

Ng at the beginning of words is pronounced the same as English words ending in sing. “Sing,” I say, then drop the si part and notice the place in my throat where the ng sound is made. Ng, I say over and over, until it feels right. Next, how to say the vowels – a as in but; e as in pet; i pronounced in two different ways depending on where it is in the sentence; o as in pot; u as in push. Consonants like k, g, t and d, I learn, are said more softly than we say them in English – the book says they aren’t sounded with a puff of air. I didn’t know that’s actually what we do, so I say them the English way first, noticing those puffs of air. Then I try without the puff. Things are starting to click.

Syllables are all emphasised equally. So Ngadjuri can’t be “nud-jury” or “naa-joorey”as I’d been saying. I put it all together and even out the syllables. Nga-dju-ri. Three syllables, even weight; Ng as in sing, a as in but, u as in push, i as in happy. Ngadjuri.

Next, the lists of words. I start with the Ngadjuri ones, randomly pick them out and say them aloud, concentrating on making the sounds. Then I go through the English list, reading each one out then saying the Ngadjuri translation a few times. Words for different animals, birds, insects and plants; words for water, fire, sky, clouds, sun, moon and stars, for people, for actions. Words like butji, malku and gundu’malku for different types of cloud formations. A word for eye – mena – and another – menawalpu – for being sharp-eyed. One for “to dance” – mutanga – and a different one – guri – for an imitative dance. Words like mulka for “to talk” and jata’mulka for “talk by sticks on the ground” – also known as “silent talk,” a skill you need when hunting. Even a word for “shaking out dust” – kunma’rindma.

When I get to the letter s, I notice there are seven forms of the word spirit – ancestral beings, spirits causing heat, spirits that tease, spirits inhabiting hills, spirit children, spirit men and women, spirit world. All this going on in the place where I’d grown up, and I’d had no idea.

Most of the words in the book came from the man in the cover photograph. Barney Waria was a Ngadjuri man born in 1873 in Orroroo, north of Clare. His mother was the daughter of a medicine man; his father was born at Booyoolie Aboriginal camp in the mid north. His surname is a variation of a Ngadjuri word meaning second male child. At some stage, it was anglicised to warrior.

An initiated elder, Barney Waria knew that his language and culture were in danger of being lost forever, so he made regular trips to Adelaide between 1939 and 1944 to tell anthropologists what he could. Norman Tindale knew him and described him as a perceptive and thoughtful man.

Histories of Australia that include perspectives of the First Peoples are more plentiful now. Some time ago, when I was reading about early colonial Australian history, I listed the dates when the capital cities were founded. It helped me piece together the waves of arrival of colonisers and convicts, and the pattern of disruption for the people already here. Sydney 1788, Hobart 1803, Brisbane 1824, Perth 1829, Melbourne 1835, Adelaide 1836, Darwin 1869.

Among South Australia’s often-touted claims to fame is that it was the country’s only freely settled state, founded at a time when a new consciousness about the treatment of so-called native people in British colonies had emerged. In 1833, slavery had been abolished in Britain after years of social pressure. The Black War in Tasmania, from 1824 to 1831, had not long ended. It was well known in British parliamentary circles that many of those living here already had resisted strongly, and that the death rates were high. This formed part of the backdrop to the plans being made in London for a new colony.

But the founding documents – the South Australia Act of 1834, Letters Patent of February 1836, and the Proclamation read out by British officials at what is now Holdfast Bay in December 1836 – were conflicted and contradictory. On the one hand, “the native inhabitants” were recognised as having occupation of the land and the right to continue to occupy and enjoy it. On the other, the territory marked out for settlement was said to consist of “waste and unoccupied lands… fit for the purposes of colonisation.”

This inherent conflict continued to play out. Land wasn’t meant to be taken up by colonists unless its original owners had voluntarily ceded ownership and been awarded compensation. But early settlers who had bought preliminary land orders in England claimed they had first choice. Meanwhile, the colony’s second governor, George Gawler, in power from 1838 to 1841, oscillated between defending the rights of Aboriginal people to their land and regarding them as inferior and not capable of entering into treaties or bargains.

In October 1839, in an act of acknowledgment of prior occupation, Gawler sent out a decree to South Australians to record the names that Aboriginal people had given to features of the landscape, and for these to be included on public maps. This, I realised, was the explanation for all those Aboriginal words for names of towns north of Clare that I’d noticed on the map of Ngadjuri country. The explanation for the mostly English names south of Clare through to Adelaide lay in the timing.

In those early years, new arrivals from England and the eastern states were pushing inland from Adelaide in search of fertile land and overland routes for moving sheep and cattle. Some, like twenty-one-year-old John Horrocks, who took up land in early 1839 before surveys were completed, named small settlements after people and places in England and Ireland.

The pattern of dispossession of the Ngadjuri people is similar to that of First Australians in many parts of the country. Europeans arrived, saw fertile land with water sources close by – which Indigenous people had been using and keeping clean for tens of thousands of years – and began to move in. They brought in large numbers of sheep and cattle that contaminated the water, trampled the ground where people grew edible plants like yams, and took over the grazing areas that kangaroos and other native animals fed on.

In those early years, Ngadjuri people were, as it was often put at the time, “dispersed.” Exposed to new diseases, many became ill and died. Those who tried to resist the settlers, or who took sheep and other supplies to feed their families, were treated as criminals and many were shot or hanged. Others were driven from their land, forced onto the country of other Aboriginal people, and later into Christian missions where, for the most part, they weren’t allowed to speak their language.

Before Australia was colonised, over 250 languages were spoken, many with different dialects. Where South Australia now lies, around fifty distinct languages could be found. Aboriginal people were naturally multilingual. Up until British contact and for a while after, Ngadjuri people were fluent in the languages of the people from lands around them, including Adnyamathanha to the north and Kaurna to the south.

Across Australia today, fewer than 120 languages remain in daily use, the majority of those in the northern and central parts of the country. At present, only thirteen are considered strong, meaning they have fluent speakers across all generations. Among these, in South Australia, are Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara. Of the remaining languages, some are still spoken by at least a few adults, but not by the children. Others have people who speak a few words and phrases. The most fragile languages are those where knowledge survives only in books and archives. Ngadjuri has been one of the latter for a long time, but in recent years Ngadjuri people have been making moves to revive it.

Karina Lester is a Yankunytjatjara Anangu woman who lives in Adelaide and works with Aboriginal communities around the state to maintain, revive and reclaim their languages. She co-manages the Mobile Language Team, located in the University of Adelaide. I’d heard her speaking on a podcast, slipping easily between her traditional language and English.

When I spoke to her from Melbourne, she talked about the pride she sees in people as they come to know their language. She sees it in the children too, a growing confidence as they develop connections to country, and with the old people.

Prior to contact, she said, people knew through language how to keep country alive and thriving for future generations. “You grew up on an area of country and you knew the place names, you knew what food to eat, how to prepare seed cakes, how to use kangaroo or goanna, how to keep rock-holes clean, why it was important to harvest only what you needed.”

Linguists used to believe that once a language had no remaining speakers, that was the end of it. But during the 1980s, with the realisation that many Aboriginal people were working hard to keep their languages and traditions alive, this belief began to give way to cautious optimism.

Kaurna, the language of the original people of the Adelaide area, is one of South Australia’s early language-revival success stories. As with Ngadjuri, there were no living speakers, only archive material. Since the early 1990s, members of the Kaurna community have been working with a linguist to reconstruct their language.

I learned from Karina that, while there is no set formula, communities and linguists draw on historical records and look to neighbouring languages for similar patterns. From this they can start to build a vocabulary and grammar, and produce dictionaries, learner guides and teaching material. Sometimes, she said, breakthroughs happen when someone comes across an old family notebook and it opens up a new source of information about language and culture.

Kaurna people are increasingly using their language, and it is being spoken at welcome to country ceremonies and utilised in the renaming and dual naming of significant places. It’s also being taught in local schools, as are about nine other South Australian languages, with around five thousand Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students studying them at forty-nine of the state’s schools.

Kaurna words are even being used by people like my mother. In the Adelaide CBD with her one day, I saw a sign saying “Kaurna.” By this stage I knew the first part sounds like a G rather than a K.

“Gurna,” I said.

“No,” said Mum.

“Gaurna?”

Mum shook her head. I gave up.

“Garna,” she said, confidently. She’s heard it often at public events.

A year after my visit to the history room in Clare, I’m in Adelaide again, this time at the State Library to watch a CD-ROM that Ngadjuri people, led by Patricia Waria-Read, a descendant of Barney Waria, made with linguists in 2009. In the closed-in quiet of the reading room, the librarian loads it for me and I sit in front of the screen, headphones on, reading and listening to the Ngadjuri welcome to country.

Alongside colourful photos of birds, animals, plants, the sun and the moon are the local words, written and spoken. There are photos of current-day Ngadjuri people, many of them children, sitting, eating and talking, while recorded voices speak the word for each action. I sit there smiling as I hear them, recognising the different sounds of the vowels and consonants, and the patterns of the syllables.

The welcome to country has three variations – one for the top end of country, one for the middle and one for the bottom. I have the Ngadjuri book with me and I check the map – Clare is located in the middle section, red hawk country. The others are bronzewing pigeon and whip snake. I try to picture Ngadjuri people giving a welcome to country to the early colonists and wonder how it would have been received and understood. Then I wonder if any of my ancestors – those Irish immigrants who’d arrived in Ngadjuri country in the 1840s – had ever heard it spoken, and what their response had been.

My sixteen-year-old nephew Dominic went to the same school as I did in Clare, many years after my time there. Recently I asked him if he’d learnt about Aboriginal history and people.

“Yep,” he said. He remembered classes in grades three to five, taught by his teachers and sometimes guest speakers.

“What do you remember?”

He replied instantly.

“The land that it was – the Ngadjuri people’s all the way up to Peterborough.”

Saying Ngadjuri came easily to him. I pointed that out and he agreed, adding with a grin, “Don’t ask me to spell it, though.”

Last week I made another trip to South Australia, for the unveiling of a sculpture of an Aboriginal woman and child. It was in Riverton, a town of eight hundred people not far from Clare. Modelled and donated by Robert Hannaford, who has had a lifelong interest in Ngadjuri culture, it had been more than twenty years in the making as the community worked to raise funds to cast and install it.

South Australia’s governor, Hieu Van Le, a former Vietnamese “boat person,” did the unveiling honours in the presence of two of Barney Waria’s descendants who’d been involved in the planning over the years. Vincent Copley spoke about ancient Ngadjuri rock art in the mid north. Vincent Branson welcomed us to country in the Ngadjuri language. I stood there, part of the crowd of well over a hundred, smiling as I recognised the words and what they meant.

In the past, when I saw Aboriginal words written down, I skimmed over them. They looked foreign and I had no idea how to pronounce them. It was easier not to try. Now I take pleasure in the sounds, and the fact that I can say them. No doubt I stumble, and do it with a strange accent, but it feels like I’m a little closer to the deeper story they hold. •

I would like to pay my respects to the Ngadjuri People and to acknowledge their elders – past, present and future. Thanks to Karina Lester and Adele Pring for background information and generous insights, and to the authors of the Ngadjuri book and CD-ROM, and the many others who helped bring them to publication.

This essay appears in Griffith Review 55: State of Hope.