Charlie Takao Dominick’s grandchildren love telling the story of what happened to their grandfather on the day of the Bravo nuclear test: how young Charlie was in the outhouse on the island of Likiep when he heard the massive fifteen-megaton blast on Bikini Atoll, 450 kilometres away; how, forgetting to put his pants on, he ran out to the other children; and how embarrassment finally overcame fear.

“It’s true,” he acknowledges with a laugh. “There is no one else in the Marshall Islands that has been exposed twice!”

Charlie had been doing jobs around the house on that morning in March 1954. “Before you have breakfast, all the leaves from the breadfruit trees have to be cleaned, the pigs and chickens fed,” he tells me. “As a young lad, I didn’t want to clean the yard, so I went to hide in the outhouse. But then, I heard noise like thunder. The blast shook the building, the trees…

“When such a disaster happens, the first place to go is to the church. I joined the boys and girls who had run there, until I realised I had no pants on – so I had to run back and put them on.”

Stories like this still dominate Marshallese politics and culture. Even as the Republic of the Marshall Islands joins this month’s negotiations for a treaty to ban nuclear weapons, many locals want people to remember the radioactive legacy of the sixty-seven nuclear tests conducted at Bikini and Enewetak Atolls between 1946 and 1958.

Just weeks after the Bravo test, two Marshallese schoolteachers, Dwight Heine and Atlan Anien, prepared a petition for the United Nations Trusteeship Council. The United States was administering the Micronesian islands as a UN Strategic Trusteeship, and the petitioners wanted “all experiments with lethal weapons in this area [to] be immediately ceased.”

Their call highlighted the importance of land as a source of culture and identity – land that was vaporised or contaminated by hazardous levels of radioactive fallout. “Land means a great deal to the Marshallese,” they wrote. “It means more than just a place where you can plant your food crops and build your houses or a place where you can bury your dead. It is the very life of the people. Take away their land and their spirits go also.”

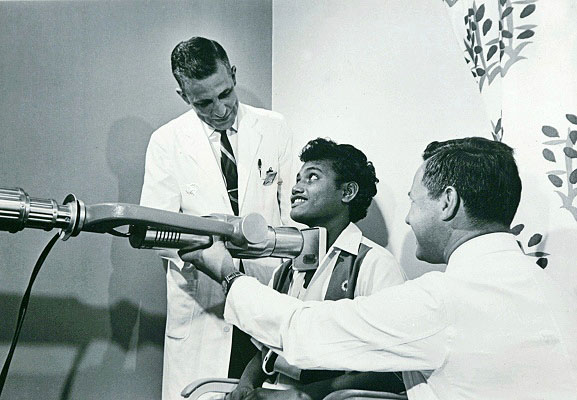

Marshall Islander Lekoj Anjain undergoing thyroid tests at Brookhaven National Laboratories in New York in 1968. He died of myelogenous leukemia in 1972. Brookhaven National Laboratories

The new president of the Marshall Islands, Hilda Heine, has followed that tradition of speaking out about the legacies of nuclear testing. Heine, who took office in January last year, is the first woman to be elected as leader of an independent Pacific island nation. A leading educationalist and the first Marshallese to obtain a PhD, she is outspoken about the failure of successive US governments to address the health and environmental legacies of the US nuclear tests.

“We face the reality that, after the US nuclear weapons testing program first began with the moving of Bikinians from Bikini Atoll, seventy-one years of inconsolable grief, terror and righteous anger followed, none of which have faded with time,” she said in a speech on this year’s Nuclear Remembrance Day, on 1 March, the anniversary of the 1954 Bravo test. “This is exacerbated by the United States not being honest as to the extent of radiation and the lingering effects the US nuclear weapons testing program have on our lives, ocean and land, and by the United States not willing to address the issue of adequate compensation as well as the radiological clean-up of our islands.”

As Marshall Islandsambassador-at-largeTony de Brum points out, “Bravo was the highest yielding of the US tests, exploding with the force of fifteen million tonnes of TNT. It was also the greatest radiological disaster in American history.”

To revitalise awareness and action, President Heine hosted a major conference, “Charting a Journey Toward Justice,” in the capital, Majuro, on 1–3 March. Over three days, hundreds of participants heard from nuclear survivors, research scientists, anthropologists and government leaders. Throughout the conference, the Marshall Islands president and the US ambassador to the Marshall Islands sat quietly in the audience, among ordinary citizens and many students from the College of the Marshall Islands and the University of the South Pacific.

For Heine, it was heartening to see the interest shown by young people in events that took place decades before they were born. “Very few of those who were there in the 1950s are still with us,” she told me. “Many of the living ones are quite old, close to the end of their life. They are very disappointed, because nothing has happened in their lifetime and they know that nothing will happen before they pass on. Therefore it’s up to us to energise the young generation to take on the mantle and go forward, because obviously it’s going to be a long fight.”

Bikini and other atolls are still contaminated with hazardous levels of radioactive isotopes, such as caesium-137, that can enter the food chain. In a 2016 paper published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a Columbia University team led by Professor Emlyn Hughes found relatively high gamma radiation at Bikini nearly sixty years after the end of nuclear testing. Low levels of gamma radiation persist on the settled island of Enewetak and the island of Rongelap.

“Bikini has radiation levels higher than the US and Marshalls governments have agreed on for resettlement,” says Hughes. “This is simply from background radiation. This is only one path and does not include the measurement of radiation in food such as coconut, breadfruit or fish.” This May, Hughes will lead another team to the northern atolls to look at exposure through food and from the ocean environment.

For decades, the US government hid the full extent of contamination in the Marshall Islands. During that period, it negotiated the Compact of Free Association, an agreement that led to self-government and independence for the Micronesian nation in 1986. As part of the Compact, the Marshall Islands government and people gave away the right to sue in US courts over damage to person and property from the tests. In return, a fund of US$150 million was established to deal with the legacies of the testing program.

Successive US governments have acknowledged the damage to the four northern atolls – Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap and Utirik – from nuclear testing. But in May 1994, the US Department of Energy released to the Marshall Islands government more than seventy boxes of newly declassified documents, revealing that the fallout from Bravo and other tests had spread much more widely than Washington had previously acknowledged. For fifty years, US governments had hidden the fact that fallout from the Bravo test had reached other atolls, including Ailuk, Likiep, Wotho, Mejit and Kwajalein.

As archivists collate the documentary history of the testing era, Ambassador de Brum believes the US government still has a responsibility to provide full, unredacted documentation from the 1950s. “There cannot be closure without full disclosure,” he says.

In 2000, following the further revelations, the Marshall Islands government submitted a “changed circumstances” petition to the US Congress, seeking increased funding to pay compensation for damage to health and property. Under the provisions of the Compact, a Nuclear Claims Tribunal issued rulings for compensation amounting to more than US$2.3 billion, a sum far in excess of funds available through the trust fund. To this day, the US Congress has failed to grant the extra funding needed to cover the Tribunal’s decisions.

Hilda Heine stresses that the United States’ responsibility for health and environmental impacts across the whole country is still a concern for her government. The 1950s documents, she says, “have now shown that eighteen other inhabited atolls or single islands were contaminated by three of the six nuclear bombs tested in Operation Castle, as well as by the Bravo shot in 1954. The myth of only four ‘exposed’ atolls of Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap and Utirik has shaped US nuclear policy on the Marshallese people since 1954, which limited medical and scientific follow-up and compensation programs.”

To coordinate further action on the nuclear program, the Marshall Islands Nitijela (parliament) recently passed legislation to establish a three-person National Nuclear Commission. The commission will develop a nuclear justice strategy and document all aspects of the US nuclear testing program.

“We only have six years left of the current Compact,” says Heine, “and so we will soon be talking to the United States on the economic provisions that are expiring in 2023. Right now, there are programs in existence that deal with the effects of the nuclear program, but the importance of the commission is that they will coordinate all of these separate programs as well as look at the strategy for going forward.”

Despite the US government’s health and remediation programs in the northern atolls, Heine believes it is time for the US Congress to respond to the changed circumstances petition. “You can see they are able to help the people of the four atolls but in very small ways, reacting to what is happening but not taking account of the root causes,” she says. “They realise that it’s a big job and it would take quite a bit of their resources. So they’d rather take care of the surface issues rather than the root causes. That’s the problem we’re facing in discussing our issues with the US government.”

Looking beyond Washington, successive Marshall Islands governments have sought to break the stalemate over the reduction of nuclear arsenals. In April 2014, the government filed landmark lawsuits in the International Court of Justice challenging the nine nuclear-armed nations for failing to comply with their obligations under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to negotiate the total elimination of nuclear weapons. Cases against India, Pakistan and Britain proceeded to preliminary submissions. But the court dismissed the lawsuits last October, ruling that there was insufficient evidence of a dispute between the Marshall Islands and these nuclear-armed nations.

Heine doesn’t regret the previous government’s decision to launch the cases. “I think it served its purpose to the extent that it continues to place the issue to the forefront of the minds of people, ly as well as in the United States,” she says. “Unfortunately, the conclusion was not what we hoped it would be, but I think it was important for us to put it out there, because otherwise, who will?”

She believes that there is a need to revive momentum on disarmament. “When you look at discussion on nuclear disarmament, it has pretty much come to a stop,” she says. “There seems to be no pathway moving forward. So I think it was important for the Marshall Islands to put some pressure on, by going to the International Court of Justice, and to keep the momentum and the discussion alive.”

This nuclear diplomacy comes alongside efforts to increase action on climate change, another environmental challenge to the low-lying atoll nation. Ambassador Tony de Brum played a key role in establishing the Higher Ambition Coalition, which linked developed and developing nations in the final stages of the negotiations leading to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

In December last year, the Marshall Islands joined 113 nations to support a landmark UN General Assembly resolution to begin negotiations on a treaty to prohibit nuclear weapons. All Pacific island states, with the exception of the Federated States of Micronesia, voted in favour of the resolution, reflecting the importance of the cold war history that saw more than 315 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests at ten sites.

Now, beginning on 27 March 2017, negotiations for the nuclear weapons ban treaty are under way in New York, with a second round of talks scheduled for June and July. Across the Asia-Pacific region, governments as diverse as Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Fiji are discussing a binding agreement similar to treaties that have abolished other classes of weapons (landmines, cluster munitions, chemical and biological weapons).

It’s no surprise that the nine nuclear-armed states will be reluctant to accede to the treaty. But the refusal of the Australian government to participate in the negotiations is a sad commentary on how Canberra’s security posture has been integrated into US nuclear war doctrines. With the nuclear ban treaty likely to be completed later this year, non-nuclear states will have the opportunity to sign on to an agreement delegitimising nuclear weapons and setting in train a process for nuclear abolition.

With its ongoing support for Extended Nuclear Deterrence, the Turnbull government is further aligning itself with the United States, even as president Donald Trump announces another US$52 billion in defence spending. When Malcolm Turnbull joins island leaders next September at the Pacific Islands Forum in Apia, Australia’s nuclear isolation will be fully on display. But the Marshall Islands, along with other neighbours, are likely to remind Australia of the folly of nuclear weapons. •