One day in November 1900, a reporter from the Sydney Evening News caught the tram to Botany and walked the last few kilometres across the sandy scrub to the La Perouse Aboriginal settlement. Among the fifty or so people living there in galvanised-iron huts was the oldest resident, Lizzie Golden (formerly Malone), who spoke of how she had spent most of her life in the area, and of how her people used to range “all up ’atween here and the head of the Georges River.”

But this way of life, which had been such a stable feature of coastal Sydney Aboriginal life throughout the nineteenth century, was changing. Many of the local people’s stopover points along the coast were being abandoned. People like Lizzie’s own son Charles Golden (c. 1877–1919), a preacher with the newly established mission movement who had married a western Sydney Aboriginal woman, were forging new links beyond the affiliated coastal zone. Sydney was also increasingly becoming home to Aboriginal people who had no previous link to the area.

The scale of change was much faster and greater than at any time over the previous century, but there was no clean break with the past; nor were all of the changes forced. As before, the responses of Aboriginal people were informed by existing connections and practices, creating something new from what had come before.

Since the early 1880s, La Perouse had been the main place in coastal Sydney where Aboriginal people could gain the assistance of the Aborigines Protection Board. Over the following decade, this help had slowly but steadily enticed Aboriginal people from across coastal Sydney. Most Aboriginal settlements in the nineteenth century contained no more than ten or twenty people, but La Perouse rarely housed fewer than thirty or forty residents, and sometimes substantially more. Within a population of between fifty and one hundred across coastal Sydney, this left fewer and fewer people to populate other settlements, and by century’s end most had closed.

Given the increasing government and religious intervention, La Perouse’s relative growth can appear to be the result of a deliberate policy of relocation. Historian Maria Nugent describes La Perouse in this period as a place “where Aboriginal people from other metropolitan camps had relocated in the 1880s and 1890s when forced out of the city,” though she also notes that Aboriginal people reject this idea of relocation in their own narratives about the settlement’s origins. In a sense, both views capture the complex dynamics at play, as Aboriginal people had limited alternatives but were nonetheless rarely forced to move. To see these processes at work, we need to zoom in and look at what happened to particular settlements in the decades after the Board was established.

Forced or persuaded? The newly constructed mission church at La Perouse c. 1894. Randwick and District Historical Society

During the 1880s and 1890s, Aboriginal settlements outside of La Perouse were increasingly vulnerable because they were small. The Sans Souci settlement, for example, was virtually abandoned in 1886 after Theresa Fussell drowned while fishing with her European husband William at Kurnell. William could not work and also look after their four children; he asked the landlord of the Sans Souci Hotel to look after two of them, and placed five-year-old Henry and three-year-old Lily in the Benevolent Society Asylum, intending that they would be fostered out while he contributed to their maintenance. The newly created foster care (“boarding out”) system was not specific to Aboriginal children, but it aimed to sever contact with birth families and establish the new guardians as the “real parents” in the eyes of the children.

If William’s longer-term aim was to take back his children, the system worked against him, and his employer Frederick Holt further decreased his chances by informing the authorities that the children had been corrupted by their parents’ drinking and should be placed with a “respectable married couple.” Henry and Lily were soon fostered out to separate families, and it is unlikely that they ever again lived with each other, or with any Aboriginal people. William died just a few months later.

With only a few people remaining at the Sans Souci settlement, the Board discontinued its assistance after 1890, which probably discouraged others from living there. An older Aboriginal man, Albert, continued to live there throughout the 1890s, occasionally joined by one or two others, but after his death the settlement fell out of use.

Authorities and the public were also increasingly scrutinising Aboriginal settlements in the 1890s. As large, old estates were subdivided and the suburban Sydney population increased rapidly, a growing public awareness of the Aborigines Protection Board and the La Perouse settlement fostered a view that there was a designated place for Aboriginal people in Sydney and an official process for getting them there. Settlements that had been used for many decades without any public outcry were now the subject of complaints to the Board, which was already monitoring them through police inspections and an annual census.

Although the Board did not gain legal powers over Aboriginal people until the early twentieth century, it developed a consistent approach to Aboriginal settlements in its first decades through the unfailing attendance of chairman Richard Hill (1883–1895) and inspector-general of police Edmund Fosbery (1883–1904) at its weekly meetings.

The Board tolerated settlements if they were small and did not create a public nuisance. The Board didn’t intervene, for example, when the annual census recorded a group of five adults living at Watsons Bay in 1892.Its view changed the following year, though, when the population increased to over fifteen people, who local police said “were likely to become a source of annoyance” to Europeans in the area. Residents of the settlement were said to be going into Sydney to obtain liquor and had “no means of earning their living at Watson’s Bay,” though the Sydney Morning Herald reported that they busked using “spear and boomerang throwing exhibitions in front of the Greenwich Pier Hotel” at Watsons Bay on weekends and holidays. The Board requested that police “warn the aborigines away, and… furnish requisitions for their passages to the places from whence they came.”

This increasing harassment in other areas made the security and stability of La Perouse more attractive, but the Board and police could not stop Aboriginal people from returning to other settlements on public land if they desired. In 1895, the Board acted on resident complaints about several dozen Aboriginal people from La Perouse, Vaucluse, the Shoalhaven district and the mid-north coast who had assembled at the public reserve at Rushcutters Bay. Recognising their limited powers, the police were “loath to move in the matter,” according to the Evening News, and only acted when Aboriginal people shifted beyond public land to colonise the nearby ruins of a former chapel on the privately owned Mona Estate. When the police ordered them to move, they simply moved “a few yards away,” back to the public reserve, and when asked to leave the area, they “could not be got to view the matter in the same light.”

The police told the Board that they had persuaded the residents to “return to their own districts,” but the Evening News reported that they had simply moved east to Rose Bay and “were sure to return at night.” Board census records show that Aboriginal people continued to use Rushcutters Bay until 1899, but it seems that all had left by the turn of the century.

The closure of the Rushcutters Bay settlement was later recalled by Trescoe Rowe, whose parents owned the Mona Estate at the time. Born in 1891, his childhood memory was that the Aboriginal residents, including his governess Harriet Baker (1860–1951), had been “removed” to La Perouse, but there was more to it than that.

Baker was an active member of an evangelical movement called the Christian Endeavour Union, which comprised a number of societies associated with particular churches. Jean Watson and Reverend William Allen of the Petersham Congregational Church had a keen interest in evangelising to Aboriginal people. With the encouragement of the Aborigines Protection Association, they started working at La Perouse in 1893, with Lizzie Malone’s son Charles Golden as secretary. By 1895 they had built a church and established the La Perouse Aborigines Mission Committee, which met at Harriet Baker’s home in Paddington. Knowing this, it seems most likely that the few remaining Aboriginal residents at Rushcutters Bay were not forced to leave by the authorities, but were persuaded by Baker and her Aboriginal associates to make the permanent move to La Perouse.

The presence at La Perouse of missionaries who were prepared to advocate on behalf of Aboriginal people added to the enticing effect of government assistance. The longstanding personal relationships between residents such as Emma Timbery (c. 1842–1916) and the Protection Board chairman Richard Hill made that assistance easier to obtain. When requests for fishing boats, repairs, equipment or rations came to the Board, Hill volunteered to take charge of them. The fact that Board members lived and met in Sydney made this opportunity available to Aboriginal people in the Sydney area. Those living at Blacktown had a similar relationship with 1890s Board member Sydney Burdekin, on whose Richmond Road property they were camped.

Emma Timbery had also developed relationships with other sympathetic Sydneysiders and was able to obtain their support from her base at La Perouse. She had known long-time Double Bay resident Eliza Robinson since they were both young women in the mid nineteenth century, and Eliza continued to visit Emma when she lived at La Perouse. Her son Leo sometimes accompanied her. At Christmas, Eliza delivered Emma “a donation of mighty plum puddings and cakes, and a supply of groceries,” the Sunday Times reported, and in 1903 she organised the building of a fishing boat for Emma and others at La Perouse. The boat was handed over at a ceremony in Manly attended by “a number of ladies and gentlemen interested in the welfare” of Aboriginal people, many of whom had assisted Eliza in paying for its construction.

With the support of Hill, missionaries and other private individuals like Eliza Robinson, La Perouse residents were able to assemble and maintain a fleet of six fishing boats, and expand or rebuild their original huts into larger, timber-framed dwellings with fireplaces and chimneys, many of which remained in use for decades. Hill was probably also instrumental in gazetting the settlement as an Aboriginal Reserve in early 1895, which gave some apparent security of tenure.

When Hill died a few months later, men from La Perouse travelled into the city from La Perouse to see if the news of his death was true, but the cross-cultural bonds between the Hill family and coastal Sydney people did not end there. Hill’s son George, and his own son George Jnr, continued to provide practical assistance to Aboriginal people in the area in the early twentieth century, taking supplies to the settlement and hosting Aboriginal people at their large Coogee estate known as Cliffbrook. Two of Richard Hill’s other sons, James and William, replaced him on the Board between 1895 and 1910, though they do not appear to have personally intervened in matters pertaining to La Perouse, as their father had.

The longer that La Perouse existed, the stronger the sense of Aboriginal attachment became, deepened by accumulating experiences and the births and deaths of loved ones. As Emma Timbery stated in response to an attempt to shut down the settlement in 1900, “there’s no more suitable place than this… and as we do no harm to anyone they ought to let us stop here… ’ere we’ve been all our lives, and ’ere we want to die.” This sense of belonging partly reflected the lack of comparable alternatives, but Aboriginal people were not prisoners at La Perouse in this period, despite some surveillance and restrictions.

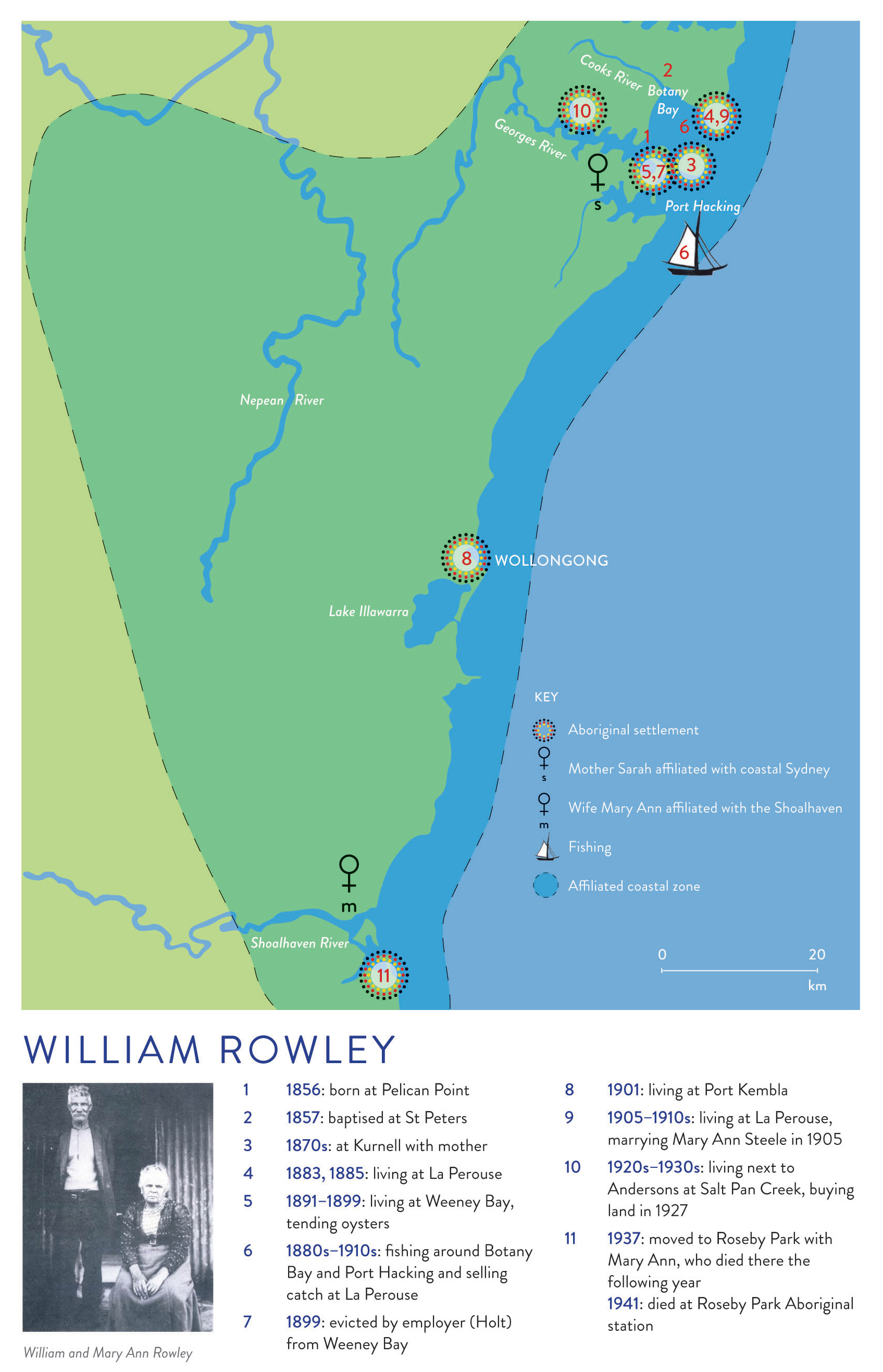

Some of the locations at which Botany Bay man William Rowley stayed in an apparent effort to live independently of government oversight. Josephine Pajor-Markus/NewSouth

They had broader connections across the affiliated coastal zone, and maintained them by continuing to travel along their coastal “beats,” much to the Board’s frustration. When around ninety Aboriginal people gathered at La Perouse in 1894, the Board contacted the Illawarra and Newcastle Steamship Companies (but not other steamer lines or railways that operated outside the affiliated coastal zone) to obtain their help in “checking the constant travelling of aborigines between the coast districts and Sydney.”

Increasing Board surveillance, suburban growth and the consolidation of La Perouse as the main coastal Sydney settlement are well-illustrated by the life of Botany Bay man William Rowley (1856–1941). Born on the southern shore of the bay, he was connected to southern Sydney through his Aboriginal mother, and to areas further south through his wife, Mary Ann, and perhaps his own family as well, as he was said to be related to Biddy Giles’s daughter Ellen Anderson. In the 1870s he lived at Kurnell with his mother, and in the early 1880s was one of the key early residents at La Perouse, but by the 1890s he returned to Kurnell on the opposite shore of the bay to establish his own place with his wife (they were officially married later), his brothers Harry and James and other family members. He tended the nearby oyster leases of the Holt family and fished around the bay and along the coast.

When he was evicted over a misunderstanding in 1899, Rowley moved to an Aboriginal settlement in his wife’s area of affiliation at Port Kembla in the Illawarra and spent the next two decades living there and at La Perouse. From the 1920s to the 1930s, William and Mary Ann lived off the Georges River along Salt Pan Creek, on a block of land at Ogilvy Street, Peakhurst. They resided there next to William’s relative Ellen Anderson, before moving to the Roseby Park Aboriginal station on the Shoalhaven River in the final years of his life.

Though he lived under the Board’s scrutiny at La Perouse on occasion, Rowley’s overall movement patterns suggest that he tried as much as possible to live independent of government oversight. Throughout his life he was able to follow the well-worn pathways that connected his areas of affiliation. For many of his contemporaries, though, past patterns of connection were becoming entangled with new lines of movement created by missionary activity.

Together with Redfern, La Perouse become the urban Aboriginal face of coastal Sydney. The two places are linked by intermarriage and half a century of Aboriginal activism. They are also now linked to virtually every Aboriginal community across the country, and new arrivals are constantly being drawn along these threads of connection. We should celebrate this diversity, this survival, and we should be eager to hear the compelling stories they have brought with them, as well as the new chapters that they have added in Sydney.

At the same time, we should be careful not to let their stories drown out the voices of those whose links to coastal Sydney extend back hundreds of generations, whose ancestors met the first Europeans, and who found a way to create an ongoing place for themselves in the oldest and largest city in the country. Theirs is a remarkable story of survival through cultural strength and cross-cultural entanglement that sits in stark contrast to commonly held views of colonial and Aboriginal Australia, and to the experiences of most Australians today. •

Paul Irish’s new book, Hidden in Plain View: The Aboriginal People of Coastal Sydney, from which this article is adapted, is published by NewSouth.