War Pictures: Cinema, Violence, and Style in Britain, 1939–1945

By Kent Puckett | Fordham University Press | US$35 | 288 pp

This ambitious, maddening, ingenious and sometimes pretentious book leaves the reader — this reader anyway — impressed by a coherence that didn’t always feel likely to emerge from sentences that make Henry James’s seem staccato. Kent Puckett’s preface helpfully asks a series of provocative questions, though, of which these two point the way most succinctly: What did it mean practically to shoot and to edit a film in the context of total mobilisation? In what ways can the form and the content of cinema specifically respond to the concept of total war? His book eventually provides valuable insights into these and related matters.

So, what is War Pictures essentially about? This is not easy to summarise pithily, but at its heart is “total war” — specifically, the second world war — and its relentless paradoxes. In Puckett’s view, total war rested on the recognition that “cherished values would have to be suspended in order to protect exactly those values.” He pursues this paradox by exploring how it accounts for the thematic and stylistic complexities of three archetypal British films of the war years, in the process spreading his net to include many others. He doesn’t just provide a detailed critical analysis of the key films, but also places them in the broader cultural context of those tumultuous years.

Sometimes Puckett’s digressions can distract the reader from the primary goal announced by his title and subtitle, but when his eyes are fixed firmly on his key films — The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), Henry V (1944) and Brief Encounter (1945) — he can be very astute indeed. His concern with the intricate and indissoluble connection of style and meaning, with style as meaning, ensures some very perceptive readings.

Puckett begins his discussion of Colonel Blimp by recalling that “it looked to many like a good movie that made for bad propaganda” when it first appeared, confusing viewers as much as moving them. He quotes Churchill’s now famous instruction to his information minister after reading the first draft of the screenplay, reflecting his belief that it would be harmful to army morale: “[Propose] to me the measures necessary to stop this foolish production before it goes any further.” Puckett examines in detail the film’s opening sequence, set in 1942, when a young second lieutenant, “Spud” Wilson, quarrels with the elderly major-general Clive Wynne-Candy, who has been “captured” in a mock military exercise. Each tries to teach the other a lesson about priorities in a situation of “total war,” Wilson favouring “brute force,” Wynne-Candy espousing more traditional approaches.

It’s not just the articulation of contrasting attitudes that is Puckett’s concern here; he is equally absorbed by how Michael Powell draws on the arsenal of cinematic style to dramatise these attitudes and recreate the worlds in which the two formed their values. He draws attention, for instance, to the use of tracking shots between periods, when cuts might have been expected, to create a meaningful elision of time and place, and to how the Technicolor palette subtly renders these differences. His precise attention to such matters substantiates his later claim that in Colonel Blimp “we can see in British cinema an effort to understand the violence of modern warfare in terms of a longer social history,” the three distinct periods of the film’s narrative rendered in such ways as to keep them distinct and, at the same time, see them as culturally interwoven.

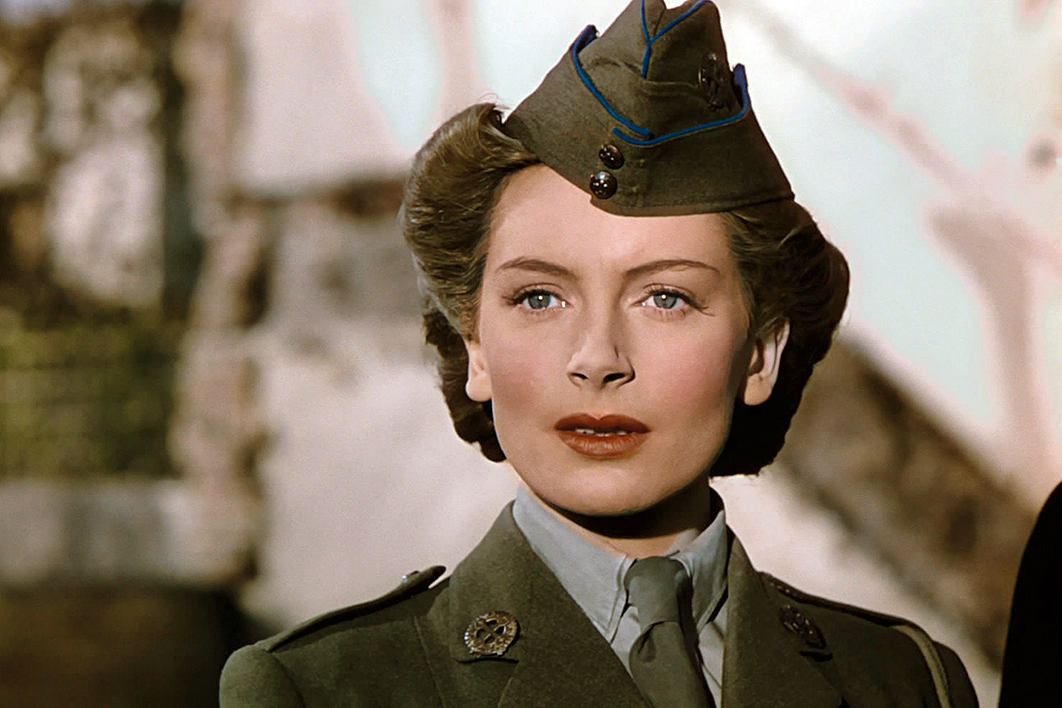

By contrast with the guarded reception Colonel Blimp received at the time, Laurence Olivier’s film version of Shakespeare’s Henry V met with almost universal acclaim “because it seemed to suspend elegantly the difference between art and propaganda, between Britain’s long cultural history and its present experience of total war.” Some later detractors were more equivocal in their praise, one of them finding it “ideologically reductive… propaganda pure and simple.” Puckett takes on board the reactions of the film’s earliest audiences as well as these later reservations, and his account of how the film establishes its links between 1944 and 1600 is marked by perceptive detail. Examining the film’s opening, for instance, he describes how the camera moves to differentiate, via a close-up, the “interiority” of a character’s experience and the “broad public experience of the stage speech.” (In a rare factual error, he later claims that Leslie Howard, who read the opening narration of In Which We Serve, takes the part of the Chorus in the opening episodes of Henry V. Leslie Banks is the right name.)

Puckett draws particular attention to Henry V’s depiction of the death of Falstaff (George Robey) and to the character of the ruffianly soldier Pistol. Falstaff doesn’t appear in Shakespeare’s Henry V, of course, having been chillingly denounced by the king at the end of Henry IV, Part II. So why has Olivier vouchsafed him these poignant last moments here? Puckett, comparing Olivier’s face as he recalls his rejection of the old knight and Robey’s as he “finally crumbles at the remembered violence of Henry’s words,” believes that “Olivier takes care to register Falstaff’s death as a real and significant loss, as something as fully momentous as the death of a king.” Again, it is the style in which this parallel is created that insists on its meaning. In the case of Robert Newton’s “eye-popping” Pistol, the author reveals his profound admiration for the famously alcoholic actor who could overplay wildly without losing his command of the screen or the audience’s attention. He traces Pistol’s role in the film’s overall propaganda agenda — and goes on, somewhat unnecessarily, to a run-through of Newton’s subsequent career, curiously failing to mention what may have been the charismatic star’s finest performance, in Lance Comfort’s Temptation Harbour (1947).

It seems to me that Puckett strains to place David Lean’s Brief Encounter in the cultural context of the war. Based on Noël Coward’s 1936 one-act play, Still Life, the film is clearly set in prewar days, was made during the last year of the war, and was released after it. He seems aware of this when he writes:

Because of the temporal dissonance between its setting and its release, the film cannot be about war in any direct way. Like it or not, though, the war was all about — which is to say physically and psychologically around or proximate to, before, during, and after — Brief Encounter.

But does this imply that “the war was all about” any film, of any genre, that happened to be made at the time? He argues that when Laura Jesson (Celia Johnson) muses that she “didn’t think such violent things could happen to ordinary people” the words would have struck a chord with many ordinary people.

But he has to push the case for the film’s inclusion in his argument about British cinema’s dealings with the war and violence and how stylistic inventiveness rendered these. He may write that “because the war had become part of what was real, the film had to rely upon that war for its structure, its style, its significance, and for the terms under which it succeeds or fails as an instance of cinematic realism,” but hard as he works at this project it never seems quite convincing. He’s on much more persuasive ground when he argues for the central dramatic importance of Celia Johnson’s face and how the camera records it. A long digression about Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia is irrelevant both to the period of the book’s interest and, specifically, to the exploration of Brief Encounter.

This is in some ways a vexing book. Since style is conceived as so crucial in relation to the films highlighted, it doesn’t seem too unfair to protest at the enormously long meandering sentences that often require re-reading to see how they stitch together. Puckett is sometimes simply over-ingenious in establishing connections that one feels couldn’t have been part of the audience’s reception of the films. He repeats himself unnecessarily, not just by twice recording T.S. Eliot’s words about music hall stars, but also in the frequent reminders of “As I’ve already argued” and similar locutions.

I draw attention to these matters not out of mere curmudgeonly zeal but to point to the book’s strength. If, despite its shortcomings, it can still maintain one’s interest as it pursues its central thesis, then this is ultimately a book to respect. It can be tough work for the “general reader” (less so for the dedicated academic audience for which it is clearly intended), but if you stick with it you’ll most likely feel you’ve been given new perspectives on films you thought you knew well. •