With the departure — possibly temporary — of two of its MPs, the Turnbull government is in a minority. Until by-elections are held, we are in unpredictable though not completely uncharted waters. An incident in New South Wales back in 1911 gives an indication of how rough the sailing might be.

In October 1910, the state’s first Labor government took office, led by former boilermaker James McGowen. After appointing a speaker, the new government had a majority of just one on the floor of the House, although it could at times rely on support from the crossbenches.

This tenuous hold on government led to a major crisis in July 1911. When lands minister Niels Nielsen, following Labor policy, proposed to repeal the legislation that allowed leaseholders on Crown land to convert to freehold tenure, two of the party’s rural MLAs resigned in protest. By-elections for their seats were set down for August, but in the meantime the government had just forty-three votes (excluding the speaker) and the Liberal opposition and independents forty-four. All the crossbenchers were now consistently supporting the opposition.

The opposition’s strategy was to defeat the government on a confidence motion. Its leader, Greg Wade, assumed that he would then be commissioned as premier, would be in a minority after selecting a speaker, and would in turn be defeated in the House. He planned to then advise the acting governor, chief justice Sir William Cullen, that the House was unworkable (because both parties had lost a confidence vote) and a general election should be held.

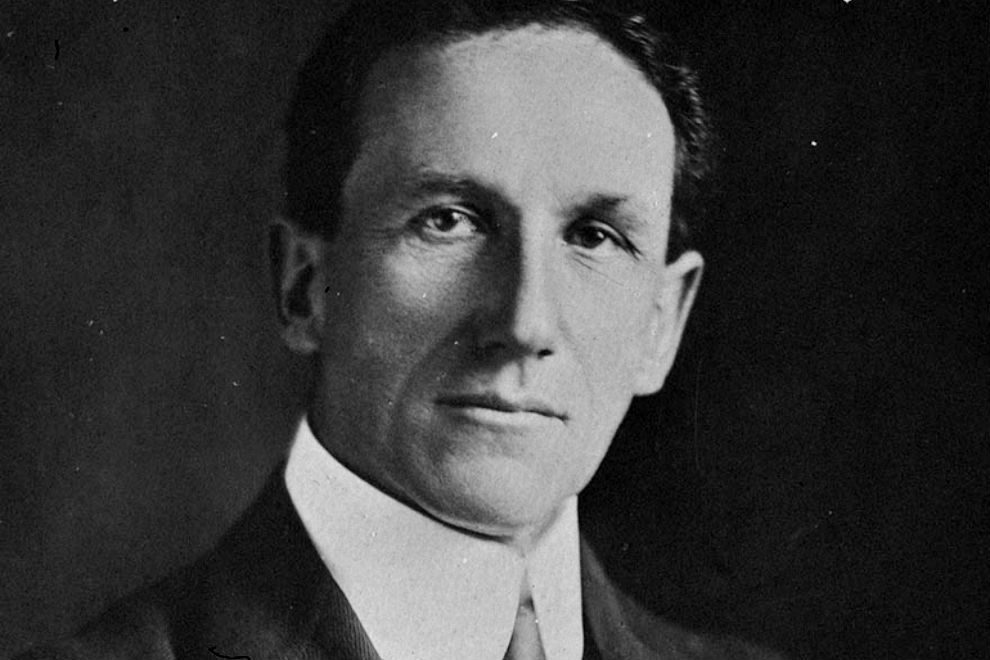

Fortunately for Labor, McGowen was in Britain and attorney-general W.A. Holman was acting premier. Holman had a brilliant mind and a touch of daring, and was a master of parliamentary tactics and procedure.

The obvious step was for the government to adjourn the House until after the by-elections. But Holman lacked the numbers to win even that vote, and the defeat of such a motion would be seen as tantamount to a vote of no confidence. Instead, Holman decided to ask the acting governor to terminate the session by proroguing the Assembly. (Prorogation ends a session of parliament without dissolving the House.) If he regained his parliamentary strength at the by-elections, he could recall the Assembly and carry on as before. But Cullen, in a questionable decision, refused the request on the grounds that Holman was seeking to avoid the verdict of parliament.

Holman decided on a risky strategy: he would resign before he lost a confidence vote. His reasoning was that Wade would then take office without any constitutional claim to an election, because Labor had not been defeated in the House. To achieve this without the opposition getting wind of it required political skills of a high order.

In the slim hope that an independent might offer him a lifeline, Holman waited until just before the Assembly was due to meet at 4pm on 27 July 1911. When this failed to eventuate, he told his driver to proceed to Government House at top speed, regardless of the traffic laws. His letter of resignation was in his pocket.

The opposition planned to move a no-confidence motion straight after question time, the first item of business of the day. Holman had arranged for as many backbenchers as possible to ask questions and for ministers to give particularly long-winded answers. Question time was still droning on when Holman strode into the chamber and announced to a thunderstruck opposition that the government had resigned. The Assembly adjourned immediately.

Opposition leader Wade now overplayed his hand by telling the acting governor that he would only take office if guaranteed a dissolution. Cullen rightly refused to have his discretion bound by such a condition. It would also have been constitutionally wrong to allow Wade to go to an election as premier, because he lacked a majority in parliament and, unlike Labor, had never had one. As no alternative was available, Cullen asked Holman to continue in office and granted the requested prorogation.

The by-elections provided little relief for Holman. He resolved the difficulty of only winning one of the two seats by persuading an opposition MLA, Henry Willis, to take the speakership, and the government limped through to the 1913 election. In spite of its difficulties, the voters liked what they had seen and Labor was re-elected with an increased majority. Ironically, it was Holman who destroyed this achievement by leaving the Labor Party over conscription in 1916.

The crisis facing Malcolm Turnbull, similar in some respects, has given rise to much ill-informed commentary and speculation, with some even suggesting that the governor-general needs to become involved. No one who remembers the events of 11 November 1975 needs to be reminded that the governor-general’s reserve powers do exist. But they are highly circumscribed and could only be used in the most extreme circumstances. To suggest that the governor-general should interfere in a political crisis of his own volition, ignoring the advice of his ministers, would take us back to the absolutist ways of King Charles I, who lost a civil war, his throne and his head as a result.

Turnbull may be able to adjourn the House of Representatives with the support of independents. Alternatively, he may decide to prorogue until the by-elections are over. The governor-general retains some discretion in regard to prorogation; today, though, he would be much more inclined to heed his advisers than Sir William Cullen was in 1911.

There have also been suggestions that a successful no-confidence motion in the House of Representatives would automatically lead to an election. The 1911 precedents are a reminder that the governor or governor-general has a duty to exhaust every possibility of forming a government before granting a dissolution.

If the government were defeated on a confidence motion, it is far from certain that Labor would be asked to take office. The major consideration is that the position is temporary and aberrant. Pending the forthcoming by-elections, the governor-general would probably adopt the view that he should let the ordinary political processes resolve the situation one way or the other. ●