The title of this essay may surprise many people. The relationship between Charles Bean and the Australian War Memorial is well-documented and the Memorial’s reverence for Bean and for his vision for the organisation is stronger now than ever. By contrast, few people know that for seventeen years Bean chaired the committee that laid the foundations for managing the official records of the Commonwealth of Australia.

The story in outline is that in 1942 Bean accepted an invitation from prime minister John Curtin to chair a committee of government officials to be known as the War Archives Committee, later the Commonwealth Archives Committee. This was an interim committee whose purpose was to make recommendations to government and oversee the beginnings of an “archives system” for Commonwealth records. The committee was to prepare the way for a permanent organisation, whose exact nature took some years to determine.

The first step was an Archives Division, established in 1952, within the Commonwealth National Library. Once staff were appointed, the scope of the division’s work expanded rapidly. Independence from the library was achieved in 1961 when the Commonwealth Archives Office came into being. By then, the Archives Committee had wound up its affairs. Bean had resigned in 1959 as the committee was winding up; his work with the committee was his last act of public service before ill health forced him to retire to a more peaceful life with his wife Ethel at Collaroy, on Sydney’s northern beaches.

To be clear, Bean was not a “founder” of what we now call the National Archives of Australia. The Archives’ origins, like those of the Commonwealth whose records it preserves, emerged from peaceful (if passionate) advocacy, discussion and debate among many people. The history is not a dramatic one — no one is known to have died in its service, as has happened at the Memorial for instance, and no cult has grown around its leaders, as it has with the directors, collectors and benefactors of the National Library and many state libraries and museums.

Founding fathers are useful in binding an organisation together in common purpose, and “ancestor worship” is common in many of the cultural, educational and scientific organisations founded in Australia at the turn of the twentieth century. The great immunologist Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet was director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research from 1944 to 1965. Long after his death many felt that his symbolic significance continued and his ghost still haunted the institute; indeed, to those within its distinctive scientific subculture and “life world,” the institute is Macfarlane Burnet.

In a similar manner, it could be said that the Australian War Memorial is Charles Bean; or almost. Undoubtedly his was the guiding vision in its evolving complexity as a memorial, museum, library, gallery and archives. His words have long been quoted on the walls of its Orientation Gallery. The Memorial’s historians and curators constantly use his histories, and a building and research fellowship are named after him. His name and image are all through the Great War collections, his personal records were among the first to be described and digitised, and his books are always sold in the shop.

What of the Archives? Today, it tends to hang the founder hat on its first archivist, Ian Maclean, who was appointed to the Archives Division in 1944, naming a research award and a meeting room in its Mitchell repository after him. Maclean is undoubtedly an important figure in the development of the archives profession in Australia and at the Archives, but he was not the first Commonwealth archivist, as the Archives has sometimes said. That honour goes to John Treloar, who was appointed as officer-in-charge of the Australian War Records Section in May 1917.

Within the Archives, Charles Bean’s relationship is not unknown, but it has never much penetrated the organisation’s sense of its history. Perhaps Bean is too closely associated with the Australian War Memorial and with war history to be entirely welcome. Perhaps founding fathers can’t be shared around. Or perhaps the Archives prefers to associate itself with peacetime Australia in a bid to distinguish its aims, its collection, its activities and its brand from the Memorial.

Many earlier attempts had been made to ensure the preservation of Commonwealth records. Archivist Michael Piggott has analysed initiatives that gathered strength in the 1920s and 1930s, beginning with the laying of a foundation stone in 1920 for a “Capitol” building. The building was designed by Walter Burley Griffin for receptions and ceremonies or “for archives commemorating Australian achievements.” But it was never built. Over the ensuing decades, various parties — notably the National Library under its Chief Librarian, Kenneth Binns — brought pressure to bear to build a national archives.

Binns’s unavailing efforts through senior levels of government lasted until “the breakthrough,” as Piggott calls it, came on 3 June 1942, when Binns, H.S. Temby, a senior official of the prime minister’s department, and Prime Minister Curtin attended a meeting of the Commonwealth Literary Fund. A discussion outside this meeting finally convinced Curtin to act. (It is extraordinary that at the height of the crisis of 1942, just two days after the Japanese submarine attack on Sydney Harbour, the prime minister should be discussing literary grants and pensions.)

Exactly what was said is unknown, but influence may have come from another direction as well, via Frederick Shedden, the most powerful Commonwealth public servant at this time. Shedden, as secretary of the Department of Defence, secretary of the War Cabinet, and secretary to the Advisory War Council, was a dedicated record-keeper. The historian David Horner has shown that cabinet record-keeping had been haphazard until Shedden instituted new procedures for preparing agenda papers and minutes. He became known for the highly efficient filing system he devised. “Documentation, thy name is Shedden,” Robert Menzies once said of him.

After Labor came to power in October 1941, Shedden became the prime adviser to John Curtin and an ever-present support. Horner believes the War Archives Committee was established essentially to house war cabinet records. Shedden’s views on the need for good record-keeping to support stable government in a time of war likely carried more weight than the more distant pleadings of Kenneth Binns at the National Library.

In any case, once the decision was made, Curtin lost little time in contacting Charles Bean, writing to him on 19 June to lay out the archives scheme. Binns probably put Bean’s name forward as a possible chair. Bean, of course, had been a guiding figure in the collection and preservation of records from the Great War, and had used archival records extensively in the writing and editing of the Official History of Australia’s part in the Great War. That history had been hampered by poor availability of departmental records and Binns knew that Bean had been using channels of his own to press for better custody of these records in the new war.

Today, the establishment of a new government committee would begin with carefully worded terms of reference and a reporting framework. Not so with this committee in 1942: Curtin’s proposal was loosely worded. The committee would investigate the matter of “collecting and preserving important documents and records created by departments and wartime authorities.” It would lay down “broad principles, which departments should be requested to observe, and to maintain a general supervision over the work.” It would meet in Canberra.

Although barely clear of the final editing of his last volume of the Official History, Bean accepted. His only proviso was to add John Treloar to the proposed list of committee members from the prime minister’s, attorney-general’s and external affairs departments, and the National Library.

With a secretariat at the prime minister’s department, the War Archives Committee met for the first time in July 1942, less than a month after Curtin’s invitation to Bean. The committee circulated a questionnaire to all departments asking about their record-keeping practices. Bean himself visited and interviewed department heads in Melbourne and Canberra. (Unfortunately, no record of these interviews appears to have survived, so we don’t know if Shedden at Defence had used the occasion to give Bean his views on good practices.)

In December 1942, the committee reported back to Curtin. It recommended that its work be expanded to encompass “all records and documents bearing upon the development of the life of Australia.” Hence, although known as the War Archives Committee, it was already taking responsibility for all Commonwealth records. In June 1946 this was formalised when the War Archives Committee became the Commonwealth Archives Committee.

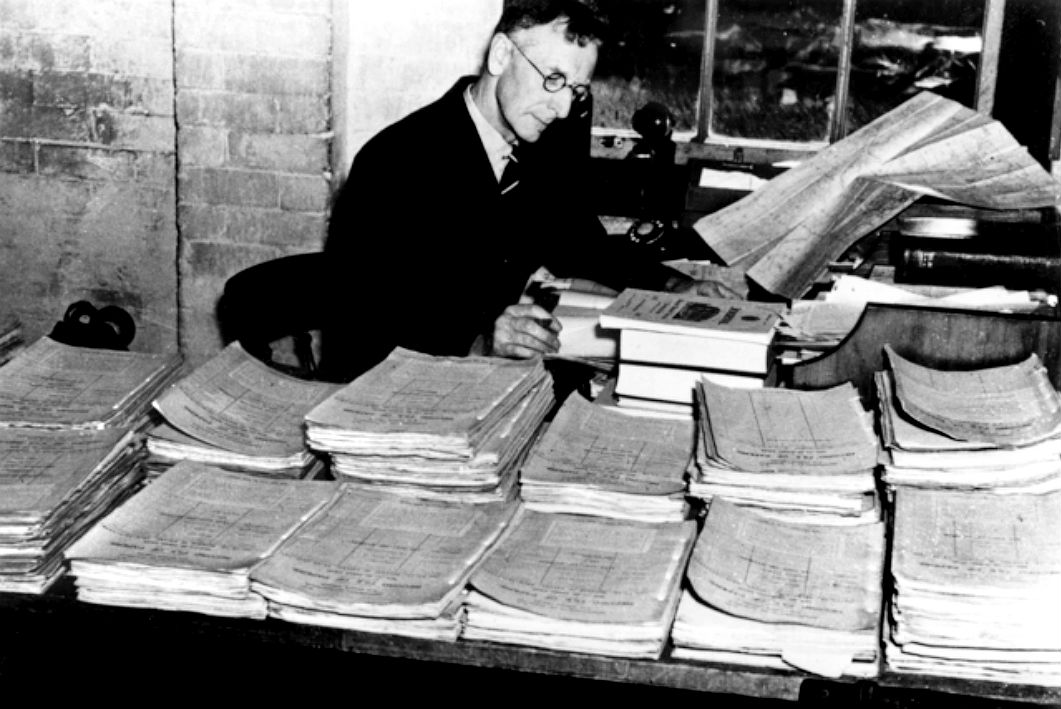

Between 1942 and 1959, when the committee began to wind up its affairs, much was achieved. It met thirty-eight times, first in West Block (two minutes’ walk from the National Archives’ current location in East Block). Its reporting was intermittent at the start, but between 1952 and 1958 it published six regular reports. The committee was relatively independent at first, but began to liaise with other authorities after the war, including the Public Service Board and the state archives authorities, to establish the infrastructure of a national archives system.

Disposal schedules were devised and promulgated. Accommodation for records of permanent value was established in the mainland capitals. And so began the work of arranging and describing records going back to 1901. Departmental records managers attended training programs in records and archives management. The question of Commonwealth archives legislation was discussed and a bill drafted, but it was shelved. A reference service was established to answer questions from researchers and from departments needing access to older records that had already been transferred.

The committee’s membership expanded to include representatives from more departments, and historian Manning Clark was appointed as an associate member in 1952 to advise on access to records. Clark’s rising prominence, marked by the publication in 1950 of his Select Documents in Australian History, may have prompted his appointment. It is intriguing to imagine Charles Bean and Manning Clark — two great historians of different generations with such different temperaments — sitting at the same committee table. Clark, though, appears to have had limited influence.

The association with the office of the prime minister was important throughout. Bean played up the prime ministerial connection in 1947 when he published an article in the premier Australian history journal Historical Studies under the title “Australia’s Federal Archives: John Curtin’s Initiative.” He described the committee’s first five years’ work, and credits Curtin with taking the initial step to prevent the loss of administrative records that occurred after the Great War. The committee always reported to the prime minister and copies of its reports were sent to him personally, generally with a covering letter signed by Bean. During the Menzies years, Bean often received a thoughtful reply signed by Menzies.

Bean’s contributions and his skill as a committee man were critical in dealing with vexing issues. Kenneth Binns had for years campaigned for the establishment of a Commonwealth archives within his library, but Bean had to balance this against other factors. The Memorial had been acquiring Commonwealth combat-related records since before the end of the Great War and from 1920 had the authority to acquire the war-related records of civilian departments, including Defence. For practical reasons it had not pressed these latter claims, but it had not surrendered them either. Now the heads of those agencies — Binns and Treloar — sat at the same committee table. Bean may have owed his appointment as chairman to Binns, but he was a long-time member of the board of management of the Australian War Memorial as well, and had its best interests to defend.

It made sense to take advantage of the expertise that both bodies had in managing government records. So, as an interim measure, they were made provisional “archives authorities.” The Memorial was the authority for the departments covering defence, army, navy, air, repatriation, information and home security, and the War Service Home Commission. The National Library got the records of all other Commonwealth departments. The division related to both past and future records. In 1944 both institutions appointed “archives officers” to establish policy and liaise with their respective departments. Axel Lodewyckx (Manning Clark’s brother-in-law, incidentally) was appointed to the Memorial in July 1944, and Ian Maclean to the Library in October 1944. Both had previously served in the army and were university graduates. Neither had any archives training, though Lodewyckx had been a librarian in Melbourne.

Treloar for the Memorial and Binns for the Library were not personal rivals particularly, but neither was especially happy with the dual archives authority arrangement. Both worried that their institutions would lose out to a permanent, separate national archives, and so it turned out. The Memorial lost its status as an archives authority in 1952. The organisation was too beset with other problems — such as the need to complete its building in Canberra, and to process its other collections — to be able to sustain the work. Bean could see this and said so to Treloar, but his old friend and colleague refused to agree.

It was a tense time in the long relationship between the two men, with Treloar bewildered when Bean withdrew his support for the Memorial as an archives authority. Only Treloar’s sudden death in early 1952 cleared the way for the Memorial to accept reality and step aside. It became a records custodian only, with no authority for policy or records management, and its reach was restricted to combat records.

In his personal papers, some handwritten notes in Bean’s increasingly shaky handwriting show him drafting recommendations to this effect. The field was left clear for the National Library. Ian Maclean, the Library’s archives officer, became chief archivist of a newly strengthened Archives Division. The Commonwealth Archives Committee shifted there, administratively and physically, with Maclean as its executive officer.

Bean, although aged seventy-two in 1951, was still capable of comprehending innovation and change in archive practices, a field that was not his own but over which he had much responsibility. In Britain that year he met the great English archivist Sir Hilary Jenkinson, author of the text that had been setting standards for archival practice in the English-speaking world for several decades. Archives was emerging as a discipline separate from history; the archivist, Jenkinson insisted, is not and ought not to be a historian. Archivists would need some knowledge of history and may be personally interested in it, but their duty is to the archives, independent of any research use to which the archives might be put.

Then, in 1954, a leading American archivist, Theodore Roosevelt Schellenberg, visited Australia as a Fulbright scholar. Bean met him at a critical time and Schellenberg was drawn into the especially vexed question of library control of archives. A government enquiry — known as the Paton Committee, after its chair, G.W. Paton — was investigating the role of the National Library, which could not sustain all the functions and purposes it had taken on. The question was whether the Library should keep its responsibility as an archives authority. Should the Archives Division become independent?

No, it should not, argued Harold White, a passionate defender of the Library’s interests who had replaced Kenneth Binns as national librarian in 1947. Yes, it should, suggested the visiting expert, Schellenberg, since this conformed with the practice in the United States and Britain. The Commonwealth Archives Committee listened carefully to arguments on all sides, and decided that the Archives Division should be a separate agency of government. This was what the Paton Committee recommended and, in 1961, this is what happened.

Through all of these developments, how are we to understand the personal contribution Bean made? Within the span of Bean’s chairing of the Archives Committee, much change occurred. On the one hand there was separation of archives from history as a discipline, and on the other, their separation from libraries as organisational structures. Bean met the two great English-speaking archivists of his day and absorbed and channelled their ideas. And yet clearly he was acting through a committee which, as the years passed, found its work and influence subsumed into a network of other agencies and individuals.

So what exactly was Bean’s personal contribution to the development of a national archives? Typically, Bean claimed no glory for himself. However, when he resigned from the Archives Committee in September 1959, he wrote to prime minister Robert Menzies mentioning two “impressions” he had gained from his nearly seventeen years. First, he was pleased that Australian archivists were ensuring that government agencies were now doing the “preparatory work while… records are still in the making.” He added that several “leading archivists in both America and England” (Schellenberg and Jenkinson, surely) had stated that this put Australia ahead of procedures there. And, second, he mentioned that he favoured the separation of the Archives Division from the National Library. That too, as we have seen, was achieved in 1961. These principles — that government archives should be separated from libraries, and that good-record keeping practices at the point of creation would ensure useful records as archives later on — underpin the work of the National Archives today.

But what of Bean himself as a leader? Paul Hasluck — journalist, historian and public servant — sat with Bean on the Archives Committee from 1942 until 1949 before he went into politics. Many years later, in 1983, Hasluck suggested in a letter to Bean’s first biographer, Dudley McCarthy, that Bean had misinterpreted the Archives Committee and his role on it. Its members, he said, saw it as an interdepartmental committee, subordinate to the different ministers whose portfolios they represented. Bean did not see it that way. He felt a personal responsibility to the prime minister and ignored the role of the prime minister’s department. Hasluck disagreed with McCarthy’s judgement that, more than anyone else, Bean had created the Commonwealth Archives, instead believing that Bean had actually delayed its creation and brought confusion to its initial arrangements.

Against this, the acting secretary of the prime minister’s department in 1949 remarked to the prime minister that Bean’s work was of great value. The success of the archives scheme depended almost solely on the cooperation of Commonwealth departments, he said, and Dr Bean’s independence and prestige had contributed largely to the satisfactory progress so far. Bean’s status as an outsider was beneficial, apparently.

Nevertheless, there is scant record of Bean’s dealings with heads of agencies and Hasluck’s judgement does ring true to an extent. In Melbourne and increasingly in Canberra, a group of powerful, elite public servants — “mandarins” — was emerging. Younger than Bean, and often from quite modest backgrounds, they were university trained in the social sciences and economics rather than classics. As the architects of a government more active and expansionist than before, and of a public service building its capacity for policy development, they found new areas of social and economic management. Many rose to prominence during the war running the major departments and their careers continued well into the 1960s. H.C. Coombs, Roland Wilson and Frederick Shedden were among them. Bean does not seem to belong in this world. Hasluck thought that Bean’s experience of life was on “a narrow face” and he had the skill of an observer and reporter rather than a commander. If true, this may have limited Bean’s capacity for networking at the highest level, and for unifying support across government for good record-keeping and archives practices.

It should be said that all government archival authorities struggle at times with the challenges of unifying support across departments, and in Bean’s time there was no record-keeping or archives professions to speak of. And yet the committee under his guidance established the fundamental principle that good archives only emerge if good records are created in the first place. Moreover, Bean acknowledged that the postwar record-keeping environment was much more complex than it had ever been before. At Federation, there had been only seven Commonwealth departments; by 1945 there were twenty-seven ministries as well as a plethora of boards and commissions set up to meet the exigencies of war. Departments shifted locations often and suffered constant staff and space shortages. The Archives Division was working quietly on a way to describe this unstable record-keeping environment. The system it eventually implemented was a huge advance in archival arrangement and description that created a distinctively Australian contribution to modern archival practice.

We can observe its emergence in an appendix to the fifth annual report of the Commonwealth Archives Committee in 1956. A test case was presented, probably written by Ian Maclean, which described the transfer to archives of 200 feet of records in 1952. The records were originally created in 1901 and had been used by five departments — prime minister’s, external affairs, home and territories, home affairs and the interior. Twenty more functions of government were administered using these records. Three registration systems had been devised to control them. How do you arrange and describe records like these, archivists wondered? By date of creation? By department? Which department?

These problems in archives management were the result of rapid administrative change within the Australian government, especially since the second world war. Bean alluded to them in his 1947 piece for Historical Studies. He did not tackle them himself but he knew they mattered. The expanded Archives Division under Ian Maclean employed a new generation of professional staff, and Maclean, with his colleagues Peter Scott and Keith Penny, built the solution — the Commonwealth Records Series system — to replace the old record group system. The series became the primary unit of description, not the agency. The series could be physically stored anywhere, and its administrative context recorded on paper. The series system brilliantly addresses the complex environments of modern government record-keeping.

Archivists working at the Commonwealth Archives Office, as it was known after 1961, continued to refine the series system and it gradually benefitted from the introduction of automated processes. We take it for granted today. Anyone who has used Commonwealth records has used the series system, probably without knowing it. It is in the DNA of the National Archives. Peter Scott was credited with the breakthrough insights for the system but he was not alone; he built on the work of colleagues and predecessors.

Bean surely deserves honour for laying the foundations that made Scott’s pioneering work possible. The National Archives missed the era of the “great man” or the “founding father.” The issues, interests and problems were and are too complex for one person. It is the series system, and not any one personality, which provides the faith and vision to bind the organisation together.

If there are ghosts walking through the database at night checking that all series registrations are clear and accurate — and I wish there were because perhaps they could help out — Charles Bean is not among them. I doubt he would be disappointed that his own role in the history of the organisation is not well-known. He didn’t personally identify with the work or the institution. He knew that the Archives would always be bigger than one person, one dream or idea. It survives by accepting and nurturing the contributions and ideas of many. ⦁

This is an extract from Charles Bean: Man, Myth, Legacy, edited by Peter Stanley (UNSW Press).