Australian Books and Authors in the American Marketplace 1840s–1940s

By David Carter and Roger Osborne | Sydney University Press | $50 | 366 pages

Hands up if you’ve ever heard of Maysie Greig, the author of The Luxury Husband, Men Act That Way and A Bad Girl Leaves Town. The Sydney-born Greig married an American (the first of several husbands) and moved to the United States in 1923. To avoid flooding the Greig market, she also used the pseudonyms Mary Douglas Warren and Jennifer Ames for her prolific romance and mystery series. By the 1930s, along with other Australian writers of “light fiction” such as Alice Grant Rosman, she was among the most popular novelists in America. She even had two Hollywood films made from her novels.

You’re more likely to have heard of Louis Becke, whose novels of South Sea adventure were compared by American reviewers to those of Joseph Conrad and R.L. Stevenson. With Rosa Praed, he flew the flag for Australian adventure and romance at the beginning of the twentieth century. And even more likely to recognise the name Arthur Upfield, who came relatively late to the American scene, emerging as a popular Doubleday Crime Club–backed novelist in the 1940s.

David Carter and Roger Osborne have traced the careers of the many “Australian” writers who penetrated the lucrative American marketplace during the decades in which a boom in literacy created a mania for romance, mystery, crime, adventure and other popular fiction genres. Some of them (E.W. Hornung, Fergus Hume, Nat Gould) are Australian only in the sense that they visited Australia and mined their experience to create exotic fictions about the colony; others (Guy Boothby, Carlton Dawe) left behind their Australian birth to become part of an international fiction market with little allegiance to location.

As Carter and Osborne stress, readers across the English-speaking world were reading the same popular fiction. It’s true that most Australian books were published in Britain, but before the US Copyright Act of 1891, which extended protection to foreign books in the US market, American publishers often pirated them. The six American editions of Marcus Clarke’s His Natural Life published before 1900, for example, were all copied from Bentley’s British edition. Clarke was surprised to receive £15 from Harper publishers, commenting, “I suppose it represents something in dollars — Harper’s conscience, perhaps!”

Under the new regime American publishers claiming copyright needed to be the first to publish a novel, or to publish simultaneously with a British publisher. Cunning operators sometimes published an advance excerpt from a book in a magazine, thus claiming first publication and American copyright for the book. For Australian writers, the road to American publication was usually through a British publisher, though a few enterprising authors found ways to reach the American publishers directly, even to the extent of moving to the United States. The now-forgotten Dorothy Cottrell left her life in remote western Queensland after sending the manuscript for her The Singing Gold directly to an American publisher in 1927. Her popular success was such that she emigrated to America, partly to avoid what Cottrell regarded as the “iniquitous taxation” of alien earnings.

American readers were not as interested in Australia and the Australian experience as they were in escapist fantasies in a new location. Those anti-romantic writers Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy did not get a look-in. But in the 1930s Henry Handel Richardson had good reason to be grateful to American readers for ensuring her place in literary history. After poor sales of the first two novels in her The Fortunes of Richard Mahony trilogy, her husband had to guarantee the British publication of the third and, in many ways, most impressive novel, Ultima Thule. It was greeted so enthusiastically in Britain that the new American publisher W.W. Norton & Co. bought the rights to all Richardson’s novels.

American sales for Ultima Thule were astonishingly high, boosted by selection for the American Book of the Month Club, which had membership of more than 110,000 subscribers. This ensured sales for the first two novels in the trilogy, and for Richardson’s earlier novel, Maurice Guest, which had maintained a small following among American readers. Maurice Guest was later adapted as a Hollywood film, Rhapsody (1954), though it was unrecognisable apart from the name of the Elizabeth Taylor character, Louise, and her love for a musician.

Norton published Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Coonardoo a year after Ultima Thule and went on to produce an American version of her Haxby’s Circus in 1931 as Fay’s Circus. This edition reinstated material that had been excised from the British edition by Jonathan Cape, and Prichard worked on it further to produce a version of the novel that pleased her more than any other. Strangely, that version has never been published in Australia, where the mangled British edition has always been reprinted. Australian publishers (Text? Sydney University Press?) please take note of this omission — an Australian edition of Fay’s Circus is long overdue.

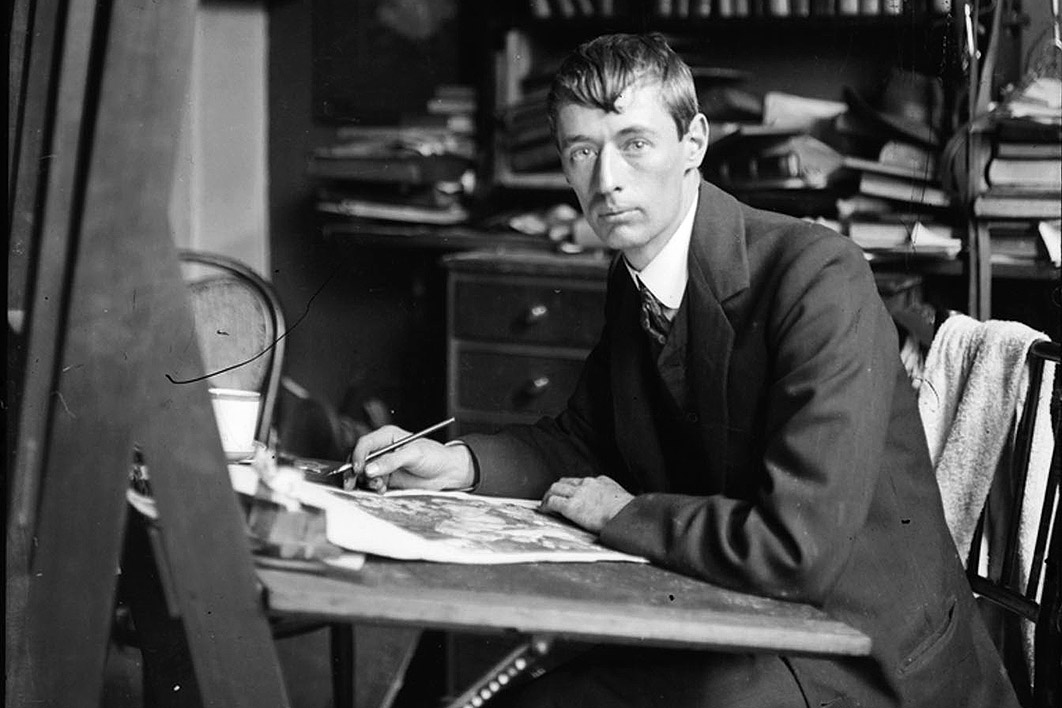

Norman Lindsay also found the American market congenial and profitable. His Redheap, published in London in 1930, was famously banned from import by Australian customs, but was published in America as Every Mother’s Son and appreciated as a modern sex comedy, “shockingly alive and scandalously amusing,” according to one critic. Lindsay headed off to New York to promote the American publication of what became a total of six books in eight years. His The Cautious Amorist also had the distinction of being banned by Australian customs, apparently on the strength of American reviews that described it as “a delectable entertainment” that might be “extremely shocking” to some readers. Lindsay enjoyed his year in America, finding the kind of serious critical response that he would never receive in Australia.

Lindsay, Prichard and Richardson made money from their American editions, reaching much larger audiences than existed in Australia. And they found American critics more open to their work than were the British gatekeepers. The American historian and critic C. Hartley Grattan visited Australian in 1927 and again from 1936. On his return home he championed Australian literature among his network of publishing contacts. The growing American interest in their work did more to boost the incomes and reputations of significant Australian writers than was possible at home, or likely in Britain.

American publishers were also crucial to the careers of Christina Stead and Patrick White. Stead lived in the United States in the 1940s and five of her novels are set there (though Americans often dispute the authenticity of the setting of The Man Who Loved Children). She had supportive friends in the American publishing world, and the critics Randall Jarrell and Elizabeth Hardwick played a vital role in the revival of interest in her work in the 1960s. White had the good fortune to win the commitment of Ben Huebsch, a publisher who never doubted the importance of the Australian’s work and ensured his American publication at times when British publishers rejected it. Some Americans understood that these two writers were worthy of interest precisely because they wrote outside the current lines of development of the literary novel.

This account of American publishing serves as a parallel literary history: of fiction that has become part of our literary canon, and of popular writing that has disappeared from memory. Carter and Osborne quote numerous published reviews and private comments by American publishers that reinforce a sense of the openness, sophistication and perceptiveness of these literary Americans. They place Australian writing in the context of the international development of the novel rather than the conventional local interest in Australianness. The Australian literary world of the same period, with its reliance on British approval and prohibitive customs laws, appears parochial by contrast.

Australian Books and Authors in the American Marketplace 1840s–1940s will serve mainly as a resource for historians interested in the way that the anglophone world shared its fantasies through popular fiction in the decades before radio, film and television overwhelmed the novel as popular entertainment. It provides detailed information on the many publishing houses in the booming American market and how Australian writers made money, and lost it to the US tax system. It doesn’t unearth much lost fiction that deserves to be remembered for its literary qualities, but it does acknowledge the brief roles of writers like Greig, Rosman and Cottrell in the history of Australian fiction. •