A very special thing is happening in our cinemas right now. A film made for the streaming TV giant Netflix can be seen for just a few weeks as it should be seen. On the big screen.

And what a film. Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma is a fictionalised memoir of his childhood — an extension, if you like, of Y Tu Mamá También, the riotous road movie that made his reputation and that of the young actor Gael García Bernal. That film was a celebration of youthful exuberance, a tender coming-of-age movie. Roma, set in the suburb of that name in Mexico City during 1970–71, takes us back further, to a time when a young family is being held together by a working mother and two maids, Cleo and Adela. It is Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio) who nurtures the children, dressing them, taking them to school, giving them dinner, settling them to lessons. Hers is the tender care to which they return. Adela (Nancy García) rules the kitchen.

Sofía (Marina de Tavira), the mother, is dealing with an enormous challenge. The father is away on business. Mostly. We do see his hand in an opening sequence, holding an ashy cigarette while attempting to squeeze an enormous American car into the narrow carriageway of the old deco apartment. Later, we see Cleo carry his suitcases out to a smaller car in which he makes his getaway to a life elsewhere.

Cleo (in real life Libo, still alive at ninety) is the centre of this story as the four children come to realise their father has left them. At first their mother shelters them from the news — he’s at a conference or on attachment to a research facility in North America — but small glimpses, overheard conversations and Cleo’s instructions to write to their father combine to create a growing understanding among the children.

Cleo’s story — an unwanted pregnancy to a martial arts–addicted boyfriend and the choice she made to have an abortion — gives glimpses of the social and political context of Mexico at the time. When she tracks down her opportunist lover he is training with a group of paramilitary volunteers. He doesn’t want to know her or to hear about her pregnancy. A scene on a makeshift barrio drill ground, where her lover is among those being trained by a North American expert, is sweetly comic.

She glimpses him once more in the havoc surrounding the Corpus Christi massacre of June 1971, in which 120 students were gunned down by Los Halcones, a group of CIA-trained paramilitaries. Cuarón handles this scene imaginatively: with Cleo, we see it through a slow tracking shot, looking down from the window of a furniture store. The muffled shots, the stunned realisation that students are falling, the panic as demonstrators and bystanders seek refuge in the store — Roma evokes a massacre more effectively than any other contemporary film I can recall.

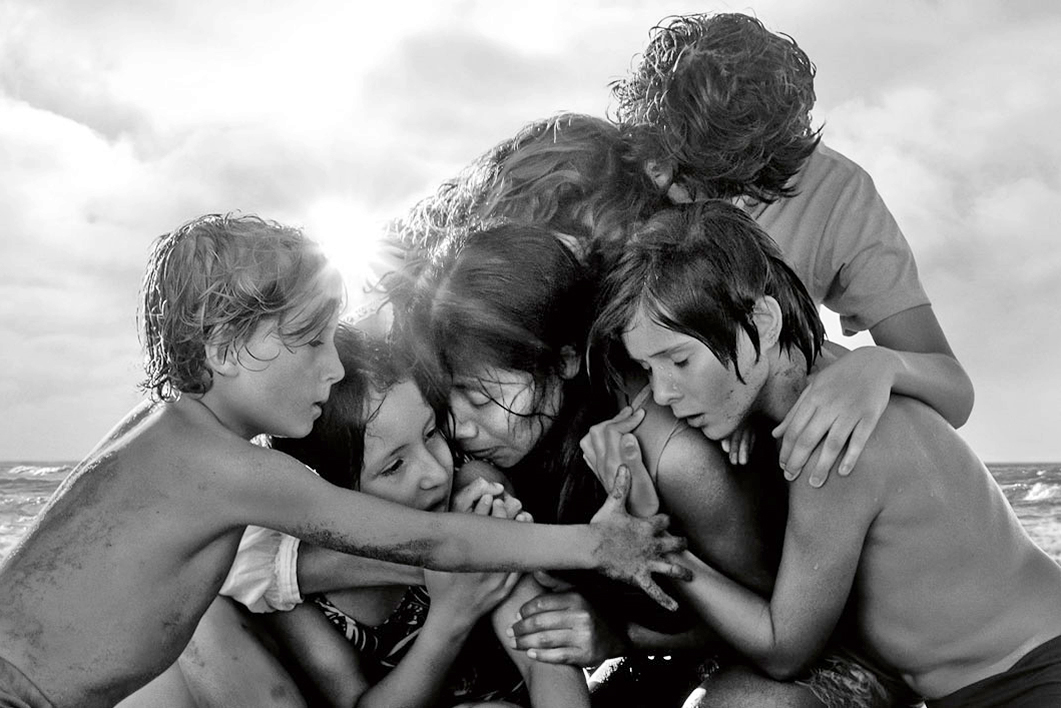

Roma is full of cinematic riches. A Christmas excursion to an uncle’s estate for a bizarre shooting trip; a New Year’s Eve carnivale at a friend’s estancia, where costumed guests carouse then the next day help put out a forest fire triggered by fireworks; a dramatic near-drowning at the seaside. Sequence after sequence creates images that glow in the memory.

This is one of the best memoir films I’ve seen since Fellini’s Amarcord, and it is touring cinemas with the Latin American Film Festival. Together with ACMI, which hosted the Melbourne screenings, Palace has managed to break the stand-off between Netflix and cinema exhibitors, which began with a dispute at Cannes in 2017.

Palace’s strategy of hosting foreign-language film festivals is now well established, and is becoming more important as the exhibition and distribution landscape changes. Along with the annual capital city film festivals, this is where film lovers will find the year’s screen treasures. Cuarón is right to say that Roma deserves the big screen. The dates are here, and it will also pop up again at ACMI and may well appear in cinemas in other states. The Netflix release will follow.

Long ago I realised that the best documentaries demand two things from film-makers: they must embrace their subjects and simultaneously stand back from them.

These days I would add a third observation: the very best documentary-makers not only embrace their subjects but walk alongside them, for as long as it takes. This is a hallmark of the films of Curtis Levy, honoured this year with Australia’s highest documentary film accolade, the Stanley Hawes Award.

Levy walked alongside Indonesian president Abdurrahman Wahid (known as Gus Dur) during the crucial transition to democracy after the fall of the Suharto regime. They had met ten years earlier when Gus Dur was a popular Islamic leader and Levy was filming the ABC series on Indonesia, Riding the Tiger. Levy’s “minder” on the series was Fakhri Amrullah Hamka, the son of a revered Islamic leader, and Hamka helped him negotiate his way through various military and police obstacles to astutely scrutinise power in Indonesia.

Gus Dur trusted Levy and invited him into the palace to live and film alongside him during a period when the president was wrestling with the military. The resulting film, High Noon in Jakarta (2009), is intimate and hilarious. Much later, the Australian government got into big trouble for listening to phone calls in and out of the palace; ironically, Levy was allowed to film many of the president’s phone calls. “The Australian government should have kept me on in the palace,” he joked.

More recently, Levy has walked alongside Terry Hicks, father of Guantanamo Bay political prisoner David Hicks, as he went first to Afghanistan to retrace David’s steps and then to New York, where he stood in a cage to protest at his son’s imprisonment. Levy’s film, The President versus David Hicks (2004), shows the remarkable growth of insight and courage in a man with little education who was determined not to forsake his son.

Levy has made other notable films, including the magnificent documentary Hephzibah (1998), a portrait of pianist Hephzibah Menuhin based on a trove of her letters and drawing on the friendship she formed with Levy’s mother during her stay in Australia. He was given incredible access to her private life.

At an OzDox tribute in Sydney this week, Levy’s former partner Christine Olsen (screenwriter of Rabbit-Proof Fence) recalled a tussle the pair had over the focus of the documentary — and particularly over Hephzibah’s decision to leave her children to the care of their squatter father and his family in order to work alongside, and eventually marry, social reformer Richard Hauser (father of Eva Cox).

In the audience at the OzDox tribute was another film-maker, James Ricketson, recently released from prison in Cambodia. He was looking well and contemplating a return to that country to continue working with his two adopted children.

When Ricketson was imprisoned in Cambodia in June 2017, a huddle of Australian film directors got together to decide how to help. Among them were Phillip Noyce, whose assistant director Ricketson once was, and Curtis Levy. A seasoned Asia traveller, Levy offered to go to Cambodia to tell Ricketson he was not alone and forgotten. Somehow he got there and gained access to the prison. Levy contracted tropical dysentery on that visit, and ended up fighting for his life in a Sydney hospital. He spent seven weeks in intensive care and almost died. Twice.

But Levy is, as documentary-maker Bob Connolly remarked, “a stubborn old bugger.” Recovered now, and remarkably spry, Levy says he has a couple more films he wants to make. The OzDox tribute ended with a hilarious clip from his last film, The Matilda Candidate (2009), in which he turned the camera on himself and stood as an election candidate on a single platform: that Australia should adopt “Waltzing Matilda” as the national anthem when we become a republic.

The serious intent was to unpack the layers of history embedded in the song, but in the process Levy persuaded his producer friend Jo Smith to act as his campaign manager. She turned out to be a monarchist, and the camera catches some furious arguments between them over the positioning of campaign boards and attempts to fit a wheezing electronic harmonium into the boot of a too-small car after it turned out to play “The Wedding March” instead of “Matilda.” A delightful film. •