A New History of the Irish in Australia

By Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall | NewSouth | $34.99 | 448 pages

Newman College: A History 1918–2018

By Brenda Niall, Josephine Dunin and Frances O’Neill | Newman College | $70 | 270 pages

From the moment they are conceived in their authors’ mind, some books are fated to live in the shadow of another. Such is the case with A New History of the Irish in Australia, which is presented by its co-authors, Elizabeth Malcolm and Dianne Hall, as a continuation of, and partial corrective to, the work Patrick O’Farrell began three decades ago in The Irish in Australia.

To be aware of Malcolm and Hall’s debt to O’Farrell, even when they disagree with him, is not to disparage their scholarship or achievement. On the contrary, their mastery of their subject matter is always evident. They have amassed and sifted a wealth of detail that O’Farrell either missed or misunderstood, which prompts a re-examination of some of his judgements.

But readers who take up this New History should be warned that they won’t be embarking on a new narrative. They are being invited into the latest round of a continuing debate among academic historians. This book, unlike O’Farrell’s, never quite manages to escape the plodding rhetorical style of the postgraduate seminar room. Compare A New History’s unremarkable opening sentence — “St Patrick’s Day in Brisbane in March 2018 saw a joyous and colourful celebration of Irish identity and its popular symbols” — with the robust challenge in the introduction to O’Farrell’s book: “Precisely who, and what, shall be called up from the ranks of the dead? Those Irish and that Irishness that came to Australia? That Irish Australia they found and made there? Their descendants? Within the moving swirl of that evocation, all precision vanishes: an elusive complexity rules.”

Malcolm and Hall’s argument is not only with O’Farrell but also with other historians, who, unlike him and unlike them, either don’t find anything particularly distinctive in the Irish contribution to the settler history of Australia or, if they do, regard it as having been largely negative. O’Farrell wrote his history to vindicate his contention that the role of the Irish in Australian history was both central and uniquely creative: “The distinctive Australian identity was not born in the bush, nor at Anzac Cove: these were merely situations for its expression. No; it was born in Irishness protesting against extremes of Englishness.”

It was a very specific Irishness that O’Farrell had in mind — not that of the Anglo-Irish, and Anglican, ascendancy class, and not that of the Presbyterian Scots settlers in Ulster, but that of those he called “the Gaelic Catholic Irish.” The abrasive and sometimes openly insubordinate presence of this large minority within settler society, O’Farrell maintained, fostered “a general atmosphere in which exclusion, discrimination and rigid hierarchies became increasingly less possible to sustain.”

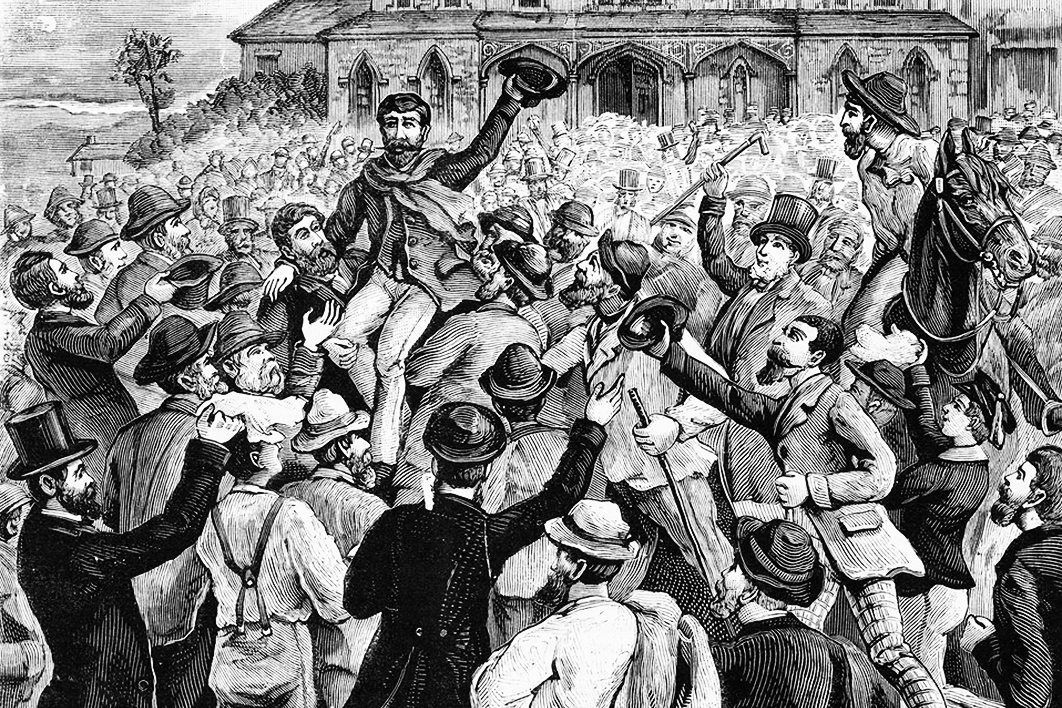

It was a bold claim, even with the considerable evidence O’Farrell marshalled in support of it, and his critics have always been able to cite counterevidence. Yes, the Catholic Irish were disproportionately represented in the violent episodes of colonial political history, such as the Eureka Stockade in 1854, but whether the Irish contribution was as decisively creative as O’Farrell believed is contestable.

Another eminent Irish-Australian historian, John Molony, had pointed to the presence of English chartists among the Eureka miners, and their prominence in the wider agitation for extending the suffrage and colonial self-government. For Molony, their role was at least as important in explaining the development of Australian egalitarianism and democracy.

Nor does the long involvement of Irish Australians in the labour movement and the Labor Party prove, as some like to believe, that this Irish presence was the catalyst for progressive politics in this country. Irish Catholics were indeed predominantly Labor voters for most of the past century, and their ecclesiastical leaders certainly encouraged their participation in the party. But Australians of Irish descent did not become prominent in Labor leadership circles until the 1917 Labor split, which acquired sectarian overtones because the Catholic archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, was a principal opponent of the Hughes government’s push for military conscription, which triggered the split. Before then, the ethnic and religious mix of Labor frontbenches had been quite different: the first federal Labor cabinet, in 1904, was comprised almost entirely of Methodists with English surnames.

It is when Malcolm and Hall wade into this broader narrative of Australian political history, as they do in the final third of their New History, that the book’s continuity with O’Farrell’s is most apparent. What is distinctive, and rewarding, in their work comes early in the book, in meticulous analyses of perceptions of racial identity in colonial society and the associated popular stereotypes. If O’Farrell’s vaunted image of Irishness as the foundation of what is most characteristically Australian remains contestable, a different, but related, thesis is easier to sustain. The struggle of the Irish-Catholic minority to achieve social and political equality with the Anglo-Protestant majority in settler Australia was a struggle to shed the racist stereotypes inherited from the relations between the rulers and the ruled in Ireland, England’s oldest colony. The peasants of the Irish diaspora — and sometimes even the educated and professional few among them — had to demonstrate that they were not the superstition-ridden, subhuman brutes the English expected them to be. In the language of today’s identity politics, the Irish had to show that they were not “the Other.”

That they were ultimately successful in this task is evident enough. There is no place, and no walk of life, in Australia today in which an Irish surname and a Catholic school on one’s CV are barriers to social inclusion or, indeed, to the highest levels of achievement (the occasional but rare jibes of satirists, noted by Malcom and Hall, notwithstanding). The Irish won. But Malcolm and Hall document the downside to the victory. In the Australian colonies, the Old World stereotyping of the Irish as less than human also reappeared in the settlers’ images of new Others: Indigenous peoples, and the Chinese who arrived in increasing numbers from the time of the gold rushes. For the Catholic Irish, to show that they were as fully human as their Protestant fellow citizens was also to show that they were not like those Others. They had to be accepted as “white,” and therefore as willing defenders of white Australia.

And so it came to be. In the racist cartoons of the early nineteenth century, the brutes from the bogs were depicted as dark, hairy and ape-like; an Irish-Catholic political leader in the first half of the twentieth century, like James Scullin, never would be.

The Irish struggle to be recognised as fully human — as “people like us” — has been replicated by successive waves of immigrants. So, too, has another notable aspect of the early Irish experience in Australia, disproportionate representation in the prison system, and how the perception of the Irish as a criminal underclass was manipulated by those intent on excluding them from full social participation. (A marker of the success of Irish Australians is that they are now over-represented on the bench rather than in the dock.) Malcolm and Hall, quite rightly, don’t exceed the bounds of historical discipline with a foray into contemporary political controversies. Readers of A New History, however, will draw their own conclusions about parallels between the Irish experience of Australia’s criminal justice systems and the experience of, for example, African migrants today.

The chief route to social inclusion for Australia’s Irish has, of course, been through access to education, not only in the Catholic school system but also in the universities, which were almost exclusively Protestant bastions in colonial Australia and remained so well into the twentieth century. Early breaches of those bastions were made by the establishment of Catholic residential colleges, such as Newman College in the University of Melbourne, which celebrated its centenary last year.

Newman College: A History 1918–2018 is not a typical celebratory institutional history. It tells frankly of conflicts and frustrations, doubts and disillusionments, and the changing visions of the Jesuits who have guided Newman since its inception, as well as chronicling the college’s impressively long list of distinguished graduates and their stellar contributions to Australian life.

The story told in Newman College is part of the wider history of the Catholic Church in Australia, rather than of Irish Australia as such. But it can be read as a coda to the stories told in A New History, and in O’Farrell’s The Irish in Australia. It is the story of a disadvantaged community — or more precisely, its less disadvantaged elements — transforming itself into a flourishing and prosperous one. In the vogue phrase of the moment, this is a narrative of empowerment. But with power comes temptation and, sometimes, a fraying of connections to the past. How many of Newman College’s students — and their families — would concede a debt to those whose stories are told by Malcolm and Hall, and by O’Farrell? Time will tell. •