Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

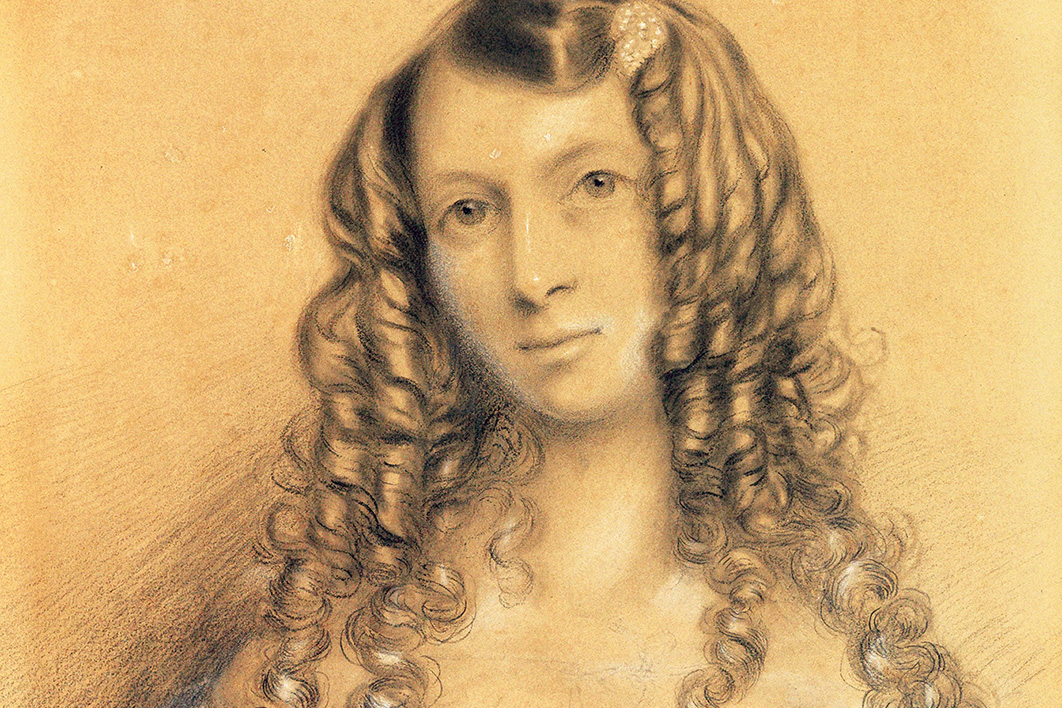

English-born Mary Allport, who settled in Van Diemen’s Land with her husband and their young son in 1831, has a claim to be Australia’s first professional female artist. As well as taking commissions from fellow European settlers, she developed a reputation as a skilled miniaturist and was an early member of the Royal Society of Tasmania.

Allport was born Mary Morton Chapman in Birmingham, England, in 1806. Her father is reputed to have run a local hotel, the Castle Inn, successfully enough to send Mary to a boarding school run by a Mr and Mrs Allport in a nearby village. Mary loved school, excelling in music and especially art, and stayed on after her studies were completed, possibly as a pupil-teacher. She married the Allports’ son, Joseph, in 1826. It was to be a happy marriage.

Joseph, six years older than Mary, was a lawyer, and the newlyweds lived just outside Birmingham. Their first child died, but the second, a son named Morton born in 1830, flourished. His parents had already decided to emigrate to Van Diemen’s Land with a group that included Mary’s brother and his wife. When they arrived in Hobart Town in December 1831, the Allports were of a high enough social status to join the colony’s elite, attending a grand dinner at Government House to celebrate Queen Adelaide’s birthday.

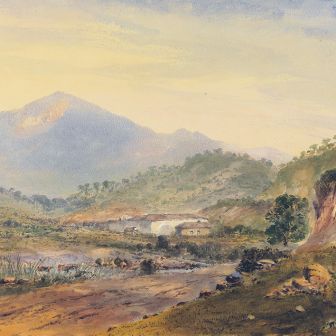

The group bought land at Black Brush, about thirty kilometres from Hobart. Life there was hard: the Allports lived in a humpy with a blanket over the entrance while Joseph built a small house, and even it had no bed and no glass in the windows. Mary staunchly described conditions as “very comfortable,” and a visiting friend “found a jovial set — bushing or roughing it in the full sense of the Word — nothing but salt meat and Kangeroo occasionally.” Joseph Allport and Mary’s brother “bear it cheerfully in fact surprisingly,” added this friend, “tho’ I know Mrs A. to be a very superior Woman.”

In her diary Mary described — without complaint — cooking roast wallaby and stuffed echidna, washing clothing by hand in cold water in winter, and making baby clothes out of old garments. This pioneering life, though bravely described, must have been difficult for a young woman unused to domestic work.

The farm brought in very little money, and in July 1832 Mary advertised that she would paint miniatures, either copying existing ones or visiting Hobart for sittings. With this advertisement she became Australia’s first recorded professional female artist. She gained a commission to paint a portrait — and then to mend it after the subject’s daughter “took off a large portion of the chin and neck with her finger.” She spent such spare time as she had sketching the surrounding scenery, and made a folio painted with flowers for the governor’s daughter, perhaps as a form of publicity.

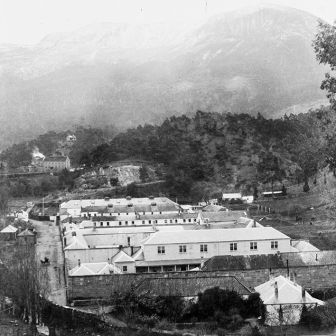

In October the family moved to Hobart, where Joseph established a large law practice and Mary managed their cramped lodgings and sketched flowers she found in the bush. “It seems to me a little paradise after my late windowless, chairless abode,” she wrote in her diary, “but the bed is the grand comfort.” Her life in these relatively comfortable and sociable surroundings — visiting, dining, playing piano duets, attending a ball at Government House — was far more enjoyable than it had been in the country.

Mary had some trouble with convict servants, who tended to drink heavily and become unreliable. In one case, a servant named Marion took Morton to buy vegetables and failed to return. It was seven hours before they were found, by which time Marion was tipsy and Mary, heavily pregnant, was beside herself with worry.

Two more convict women proved similarly unreliable, and Mary was without a servant when she went into labour. A baby girl was born safely with the aid of a midwife. With two young children, Mary’s diary petered out, but a later one, in 1853, shows that much of her time was taken up with caring for the family and household chores such as ironing, sewing and cooking.

As Joseph’s income grew, the Allports moved house, first to a cottage and later to a large house, Aldridge Lodge. Mary bore five more children, three of whom died young — two as babies and one aged six, who drowned in the garden pond. As well as rearing the children and running the home, Mary continued her art, painting more miniatures. She also taught drawing to her children and to friends. She fitted in painting around her household duties and did not gain particular acclaim at the time; she did not sell her paintings, and tended to be overlooked among better-known male artists, including John Glover and Samuel Prout.

Mary Morton Allport seated in bushland with grass trees, photographed by Morton Allport, c. 1820–60s. Libraries Tasmania, 607997

Although Mary is not seen now as a first-rate artist, her paintings are very attractive and many have historical interest, such as her depiction of an early Hobart regatta in 1842 and another of the Great Comet of 1843, seen from her garden in March of that year. Allport also produced many paintings of women with their families and involved in activities such as reading music, which, apart from their charm, are invaluable for those studying the position and activities of women at the time.

When Hobart’s first art exhibition was held in 1845 it mostly comprised European works lent by their owners. Among the small selection of paintings by local artists was Allport’s The Flowered Waratah. As a local reviewer described it, the painting was “executed by the fair artist with her usual ability, and in a rather different style from that so minute and delicate which is displayed in her drawings on ivory, of indigenous plants and flowers.” Allport appears not to have taken part in the next exhibition, in 1851, but showed two paintings in the Art Treasures Exhibition of 1868: My Pets and Portrait of John Glover. “The work of a talented lady,” was the mild comment of one reviewer.

The final exhibition at which she showed paintings was held in 1863. Allport contributed a view of the city of Litchfield in England, which was given a prominent place and praised as “well painted… a fine effect,” and A Group of Tasmanian and New Zealand Flowers. Despite its “almost microscopic” detail, the reviewer did not think highly of the second work, instead praising another flower painting as the best in the exhibition.

Joseph Allport died in 1877, and after a long widowhood Mary followed him in 1895, having reached the then-grand age of eighty-nine. She spent much time teaching and encouraging her granddaughter Curzona (Lily) Allport, a highly talented artist. Mary Morton Allport’s artistic recognition didn’t come until her great-grandson Henry Allport left his collection, including many of his great-grandmother’s works, to found the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts in Hobart. •

Further reading

“Introducing Mary Morton Allport and Her Journals,” by Joanna Richardson, Tasmanian Historical Research Association: Papers and Proceedings, 2007