Bedlam at Botany Bay

By James Dunk | NewSouth | $34.99 | 306 pages

Once upon a time I hoped to write a novel based on the life of Esther Abrahams, a First Fleet convict who was possibly the first Jew to set foot on this continent. Apart from the little we know of her story, Abrahams is of interest because of her relationship with George Johnston, one of the leaders of the famous (or infamous) Rum Rebellion of 1808, after they met on the Lady Penrhyn in 1788. Macarthur’s machinations meant that Johnston took the rap for the rebellion and was cashiered out of the New South Wales Corps and out of the colony altogether.

By the time Johnston was eventually allowed to return, a new governor, Lachlan Macquarie, had arrived with a mission to improve the morals of the colony. Macquarie encouraged Johnston to make an honest woman of Esther. The couple married, their children were legitimised, and the family prospered. But when Johnston died, the children turned against their mother and tried to have her committed. Headstrong she apparently was, and not averse to a drink, but was she actually “mad,” or did at least one of her sons see advantage in taking control of her estate?

Esther doesn’t play a major role in Bedlam at Botany Bay, but her story embodies some of the themes explored in the book by James Dunk. She believed that the litigation initiated by her children had more to do with avarice than concern for her sanity. But she lost that battle, and eventually lived with her son George, who was given charge of her affairs. Women at the time were especially susceptible to being locked away for family convenience or for control of property, but Dunk makes it clear that men could be similarly treated, and too often were.

Stories like this are at the heart of Bedlam at Botany Bay, a meticulously researched investigation of the proposition that something in the nature of European colonisation made the early settlers, convict and free, particularly susceptible to what was generally called (without our present-day recourse to specificity or euphemism) madness, mania, melancholy or lunacy. Not that it was necessarily the colony itself that drove people to the edge. Many of the condemned who languished on Britain’s hulks and in its jails at the end of the eighteenth century had manifested mental illness while waiting for the gallows. Transportation might have been a reprieve, but for some it came too late to regain mental stability, and by the time they arrived on the other side of the world their illness was well progressed. Then came the challenge of adjusting to exile, with family and community ties severed and survival harshly tested.

Dunk’s research wasn’t without its challenges. For the period he is examining — roughly from the first arrivals in 1788 to the end of transportation and tentative steps towards representative democracy in 1842 — official records of madness were thin. Indeed, the colony had no proper mental asylum until the 1830s (the one opened in renovated barracks at Castle Hill in 1811 scarcely qualified as such). Yet, as Dunk attests in his introduction, the paucity of medical records was “a kind of liberation” calling for “a different sort of history,” one in which evidence is drawn from a multiplicity of sources through the whole of society, making for a richly woven fabric of storytelling — a fabric that creates further historical understanding.

Madness came in various forms, was attributed to various causes — alcoholism, for instance, loomed large — and was classified as permanent or temporary: dementia or idiocy typifying the former, delusion the latter. These illnesses cut across the social classes that characterised Botany Bay right from the start.

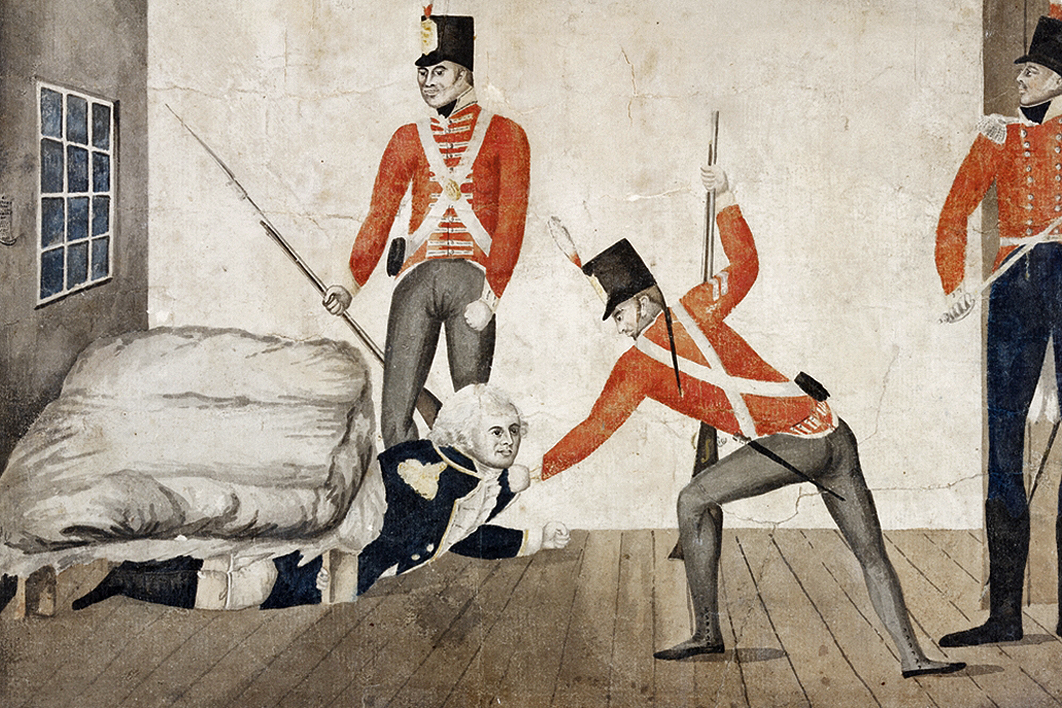

Those class divisions erupted in the Rum Rebellion, the signal moment in colonial history when free settlers and members of the New South Wales Corps combined to depose the colony’s governor, William Bligh. I mention this event because Dunk himself singles it out for its reverberations as the colony grew, as evidenced by the eventual, and sharp, mental decline of some of its key players, and chiefly of John Macarthur, whose role in the rebellion and the colony’s developing economy is well known.

Macarthur hailed from Plymouth, where his family had bought him a commission in the army. With persistence he was able to transfer to the Corps in Sydney. Though he arrived with little capital, he began raising sheep on what Dunk calls “the increasingly large grants of appropriated land which were the fruit of his prodigious talent for developing patronage networks.” This talent extended to his role in advancing the wool trade with Britain. In a sense, the more we learn of his story, the more Macarthur — with his “private despondency,” growing eccentricity and eventual decline — can be seen to personify the tensions that plagued the settlement from the outset, roiling ever wilder as it grew.

Yet there are inevitable absences in Dunk’s analysis. Because of the nature of his sources, he can only allude to the dispossession of Aboriginal people that formed the basis of Macarthur’s fortune, or the damage in the wake of introducing hard-hoofed animals. In his final chapter Dunk acknowledges this lack, while referencing Newcastle University’s massacre map as a gateway to further study. He also concedes that the sources leave insufficient trace of women’s experience of madness, as his relatively brief treatment of Esther Abrahams illustrates.

What, if anything, does any of this say about the rates of mental illness and suicidality in Australia today? The answer is necessarily speculative. But history requires imaginative and interpretative skills as much as adherence to facts. What we are only starting to grasp about the effects of intergenerational trauma may yet provide a key to understanding more about what has made Australia peculiarly Australian. Dunk can do little more than hint at this, but it’s an interesting path to pursue. Bedlam at Botany Bay is a fascinating read and an important addition to the complex picture a new generation of historians is making of our past. •