It’s now nearly four months since the Morrison government’s re-election and nearly three months since Adani received the critical approvals for its Carmichael mine–rail–port project. Adani has been emboldened by both developments, most notably in its willingness to crush opposition from Indigenous traditional owners.

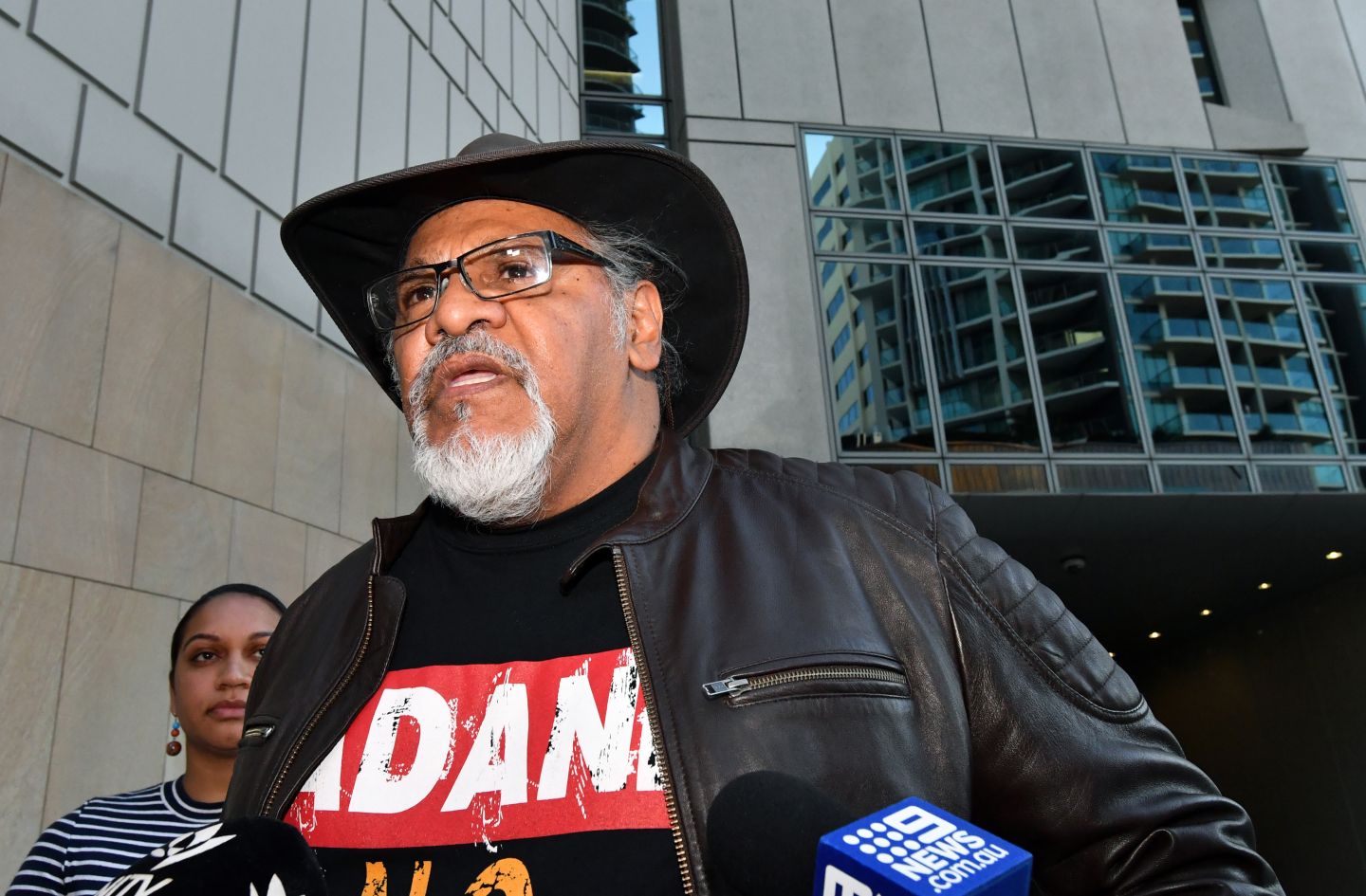

Last month the company carried out its threat to bankrupt Adrian Burragubba, the leading Indigenous opponent of the mine, who was unable to meet an order for court costs. At the same time, the company had secretly reached an agreement that the Palaszczuk government, which is running scared after the federal election result in Queensland, would extinguish native title over the mine site.

Remaining approvals, such as the lease on Moray Downs land for the workers’ camp and airport, have been finalised, and a royalty deal will reportedly be concluded soon. But Adani has yet to negotiate access to the Queensland rail network. Its owner, Aurizon (formerly the publicly operated QR), is coming under pressure from the public and large shareholders to limit assistance to what is legally required.

Despite these delays, the recent rhetoric of Adani and its backers suggests the project ought to be well under way by now, with thousands of jobs on offer. In reality, Adani has advertised just twenty-five jobs over the past month (as at 5 September), according to the company’s jobs portal, and no more than one hundred since the election, not even enough to offset cuts made last year.

It’s possible that this is simply a steady and orderly process of development on Adani’s part. If so, the company needs to pick up the pace soon if it is going to start exporting coal by its publicly stated target of 2021.

Alternatively, it may be that pressure to stop new coal projects has left Adani without partners for crucial parts of its work. As I wrote recently in relation to insurance in particular, the number of companies willing to back new and existing coalmines is shrinking, and the costs are bound to increase correspondingly.

More broadly, media reports suggest that GHD, which is carrying out the rail design work, is bearing significant reputational costs. Given the unhappy experience of previous engineering contractors like Worley Parsons and AECOM, it’s surprising a firm with an eye to the future would pick up this poisoned chalice.

That seems to be the view of another big engineering firm, Aurecon, which has just announced a break with Adani. Despite copping abuse from resources minister Matt Canavan, Aurecon presumably judges that it will be around long after Canavan has gone, and that the long-term costs of planetary vandalism is too much to bear.

Then there’s the operation of the railway. Aurizon seems unlikely to take it on, and another big operator, Genesee & Wyoming Australia, has said it won’t touch it. That leaves Pacific National, whose owners include at least one organisation, the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, that’s coming under pressure to divest from fossil fuels.

A final possibility is that the ultimate owner, Gautam Adani, is still playing for time, hoping to extract yet more government support before committing billions of dollars of his own money to a project that can’t possibly be sustained in commercial terms. As an Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis has shown, the whole plan now depends on a crony-capitalist deal involving Adani, his close friend Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and the government of Bangladesh.

Even so, without more financial support from Australian governments, it’s hard to see the project paying off. And it’s at least possible that part of the deal, now being challenged in Indian courts, will fall over.

While Adani has received an outsize share of attention here, the broader issue is the need for an orderly transition away from coal-fired electricity generation, and ultimately away from all burning of fossil fuels. If such a transition is to be feasible in the couple of decades available to us, no new thermal coal mines, or major expansion of existing mines, can be justified — and that applies to proposals such as Shenhua’s Watermark mine near Gunnedah and the New Hope mine in Acland, near Toowoomba. •