I was sitting on the concrete floor of the Mitchell Library basement in 2008 when I first saw the name Zora Cross. Working as an editor at the State Library of New South Wales, which houses the Mitchell, I was preparing a small display on early Australian book publishing. I’d taken the old wooden lift down to the “stack” to check a reference in a book of letters to and from the publisher George Robertson — known through his forty years of publishing as Robertson, the Chief, the Master or GR.

I came across a set of letters about a poetry collection, Songs of Love and Life, which was published in 1917. It was clear that this book had been a publishing sensation, but I’d never heard of it or its author, Zora Cross.

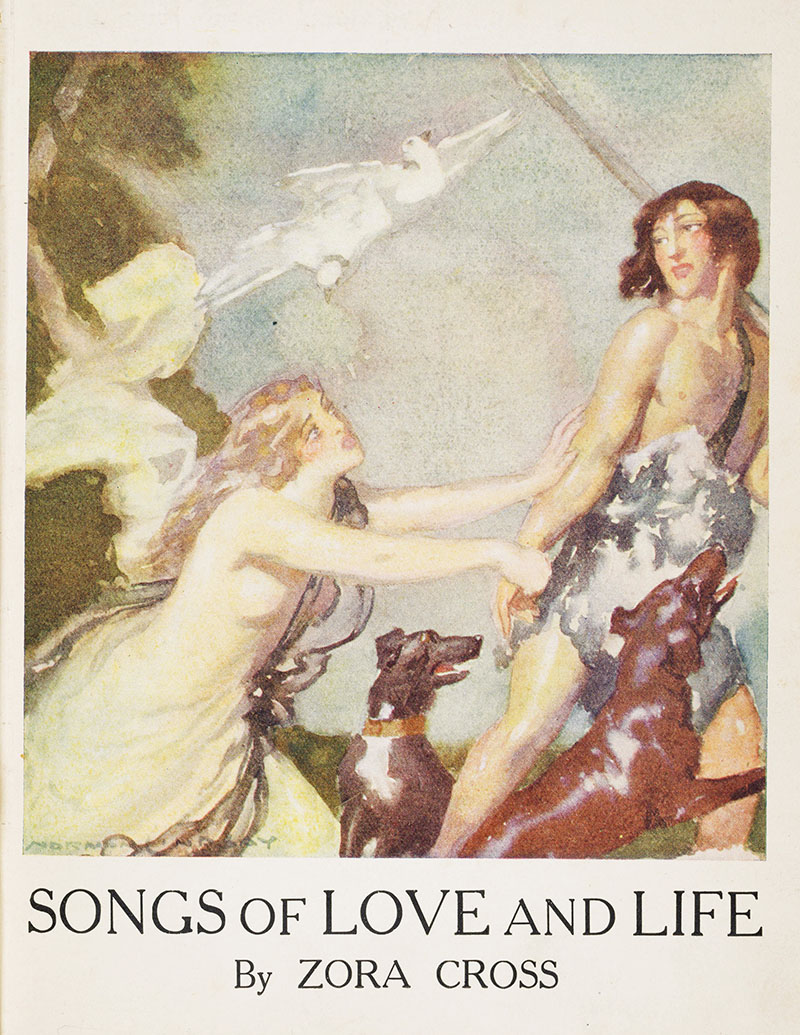

Robertson initially turned down the manuscript without reading it. But he saw a copy of the self-funded paperback in October of that year, opened it at the poem “Memory,” and quickly bought the rights. In this inferior edition, he told his assistant Rebecca Wiley, was the “great poetess of the age.” He asked Norman Lindsay to illustrate the Angus & Robertson edition, but the artist refused on the grounds that women couldn’t write love poetry (although he did produce a cover design). Robertson was undeterred. He believed that Zora Cross would endure as a household name along with the great sonnet writers, from William Shakespeare to Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Robertson rushed out a new edition before Christmas and before the second conscription referendum of the first world war. Songs of Love and Life — with fifteen extra poems and a portrait of the twenty-seven-year-old author — would be reprinted three times and sell about 4000 copies, a figure that a lot of authors would be delighted with today, let alone when Australia’s population was five million. Soldiers took it to the trenches and many newspaper inches were devoted to the author’s genius and courage.

I was intrigued by this success in the face of Lindsay’s dismissal, and by a letter Zora wrote to Robertson after receiving his publishing offer. “My heart is tired from years of disappointments — disappointments in love, in work, in myself — in all things,” she told him. “I have suffered alone and let no one know.” She wanted him to think of her as a child. “Then you will understand me and be able to forgive those thoughtless things which might otherwise seem unpardonable.”

The cover of the 1917 edition of Songs of Love and Life, with Norman Lindsay’s illustration.

I liked the way her letter breached the convention of how an author should communicate with her publisher, and I wondered about the nature of her suffering and her sense of being out of control. I began an obsession with this dead writer, which would reach a point where one of my children asked me on a car trip if Sydney’s Cross City Tunnel was named after Zora Cross.

The first four lines of the poem “Books,” from Songs of Love and Life, are burned into my mind: “Oh, bury me in books when I am dead, / Fair quarto leaves of ivory and gold, / And silk octavos bound in brown and red, / That tales of love and chivalry unfold.” Zora Cross is very much buried in books, and literary and publishing history haven’t always been kind to her.

Born in Brisbane in 1890, she moved to Sydney as a teenager and was a primary school teacher and an actress before turning to writing full-time. In the 1920s she wrote an acclaimed war elegy and one of the earliest introductions to Australian literature. Her novels, set in Queensland, were published in London. She produced an abundance of poetry and journalism into the next decade, and although her fame diminished after the second world war, she continued to write poetry for major journals and newspapers.

Towards the end of her life, Zora Cross was thought to be among the leading female Australian poets of the early twentieth century. But in 1964, the year she died, she was accused of “stuffed-owl excess” — for loading her verse with classical references — and was treated coolly or left out of the literary histories that followed.

When many Australian women writers were rescued from obscurity in the 1980s, Zora Cross was not among them. She was a difficult figure to resurrect. Her poetry didn’t always suit the tastes of the times, and the extent of her feminism could only be seen through the sum of her work, much of it hidden away in newspapers and magazines.

Dorothy Green’s Australian Dictionary of Biography entry on Zora Cross, first published in 1981, credits her with “the first sustained expression in Australian poetry of erotic experience from a woman’s point of view.” In Green’s largely sympathetic account, Zora Cross’s place in literary history is unresolved. She had a “true lyric gift” and could write with “surprising dramatic strength,” but some of her work was “somewhat monotonous” and of “little artistic importance.” Green writes that Zora’s relationship with the Bulletin’s literary editor David McKee Wright had “scandalised literary and journalistic circles in Sydney, mainly because it was mistakenly believed that Wright had abandoned his responsibility for his four sons.” Literary and moral judgements were intertwined.

Believing Zora Cross had been unfairly neglected, literary historian and poet Michael Sharkey began researching her biography in the early 1980s. After interviewing her surviving family members, and publishing an article about her in 1990, he was drawn away by other commitments and eventually changed his focus to David McKee Wright. Sharkey published a biography of Wright in 2012, and gave me his research material on Zora.

In recent years, Zora Cross has received attention as one of the first Australian women to write about sex, as a poet of the first world war, and as a novelist of colonial Queensland. Outside Australian literary and publishing history, though, she is largely forgotten. When I ask people if they’ve heard of her, a few remember reciting “Memory” at school in the 1960s.

Browsing in a second-hand bookshop in Sydney’s inner west, I tell the owner — a woman originally from Canada who has lived in my suburb for at least twenty years — that I’m writing a book about Zora Cross. “But no one remembers her!” she shouts across shelves of dusty poetry and fading biographies.

When I had a sense of how Zora Cross fitted into Australia literature, and had ordered a copy of Songs of Love and Life from an online book dealer (with her portrait torn from the front), I began transcribing the letters she wrote to leading literary figures: George Robertson, critic Bertram Stevens, writer and activist Mary Gilmore, poet and professor John Le Gay Brereton. Much of this correspondence is held in the Mitchell Library collection. Even as a child, she wrote dozens of letters to Ethel Turner’s “Children’s Corner” in the popular Australian Town and Country Journal.

Typing thousands of words from her letters, I was carried along by thoughts and phrases that could only belong to Zora Cross. It was clear that she had left behind something just as valuable as her published work: a voice that has not lost its ability to engage the reader.

Across several archives — including twenty-one boxes of her papers in the University of Sydney’s special collections library — is an intimate record of striving, getting into trouble, writing and raising children. Many biographers, especially of women, are frustrated by their subject’s faint presence in documentary records. My challenge wasn’t in finding material, but doing justice to it.

In August 2012, I wrote to Zora’s daughter April to tell her I was fascinated by her mother’s life and work, and was attempting to write her biography. I hoped we could meet. At lunchtime the following day, in the children’s section of Dymocks bookshop in Sydney’s George Street, I answered my phone to an unknown number. In a shop that was once the main rival to Angus & Robertson’s Castlereagh Street store, I first heard the voice of Zora’s only surviving child, then eighty-eight years old.

April appreciated my letter. She had called immediately but would also write. In her letter, which arrived the next day, she expressed her disappointment at the way her mother had been remembered. “She certainly deserves to have a well-researched and I hope sympathetic history of her life,” April wrote. “She has had such a bad press over the years being regarded as some sort of femme fatale instead of the serious poet she was.”

April aimed a fine point of detail at the seductress myth: “She was a dedicated writer who worked all day and every day of her life at her old Remington typewriter with a pen close handy for the innumerable corrections that she made.” April would tell me that her mother worked all night if her writing demanded it, still typing when the light came on at the stationmaster’s house in the distance.

Up close, the archetype of the femme fatale dissolves and the serious writer can be seen in two ways. Up to the end of her life, Zora Cross was a writer producing draft after draft but never happy with what she had written. And she was a writer who realised an ambition that began in childhood: to die with a pen in her hand.

I set out to write a conventional biography, but I was drawn to an idea of a life that was made up of relationships. Each of Zora’s relationships shows a different side of her personality and each has its own tensions.

Her nine correspondents were all preoccupied — or others were preoccupied on their behalf — with preserving the memory of their work. Zora preserved not only her work, but the ordinary moments in her life — the books she read, the times of the trains, the plants in her garden, and the moment she accidently touched the arm of a married literature professor during an excited conversation about Elizabethan drama.

Over time, Zora and I developed our own relationship. I began to suspect this when, as I started to write the book, I occasionally put myself into the narrative. When I read Zora’s profiles of women writers from the late 1920s and early 30s, I found that she did the same. She may be buried in books, but she has given me the means to revive her. •

This is an extract from The Shelf Life of Zora Cross, published this week by Monash University Publishing.