How did Australian aged care reach its current nadir? Countless inquiries and reviews have probed this question; postmortem after postmortem has dissected the policy and regulatory failures that have wrought the present abysmal state of affairs; a surfeit of recommendations have been handed down; revised guidelines and principles adopted; advisory committees formed; stakeholders consulted — yet here we are, a prosperous nation with one of the worst aged care systems in the developed world. And in spite of the scorching spotlight of the royal commission into aged care quality and safety — the final findings of which are due in November — there is seemingly little political will or vision for change, and no clear road map.

The more I think about the aged care impasse, the more I have come to see the sector’s seemingly intractable issues as symptomatic of a more fundamental failure: one that underpins the litany of ineffectual policy reforms, deficient regulation, negligent provider practices and lamentable outcomes experienced by many aged care recipients. This failure is not unique to politicians or providers, but their failure in this respect is more consequential. It is a collective failure that implicates us all. Fundamentally, the failure of Australian aged care is a failure of imagination.

“For all the death, we also die unrehearsed,” Les Murray writes at the end of his poem “Corniche.” This line of Murray’s has been on my mind lately, because it strikes me as incisively true, and yet not. Death is the surest thing we know, but its particular contours are unknowable. It is out there for each one of us like a distant comet in the night sky, hurtling towards us at an incalculable velocity. We do not know when death will reach us — only that it will.

And yet it could also be said that in the twenty-first century, we rehearse our deaths continuously. We live in a golden age — a dark age, perhaps — of cinematic and literary dystopianism. We voraciously consume scenarios in which natural disaster, climate change, alien life forms or malevolent technology threatens our survival. We contemplate death and the ways we might die all the time.

The appeal of this dystopian ideation is clear: it offers us a cathartic encounter with fears of societal collapse and the animalistic return to Darwinian imperatives, and then a predictable return to order at the narrative’s end. The lights of the movie theatre come up, the last page of the novel is turned, and we are back in our own unscathed bodies, exhilarated to be spared.

Many recent cinematic dystopias centre on the body’s vulnerability and fallibility. In the blighted desert landscape of Mad Max: Fury Road, humans are vampirically mined as “blood bags” and select women are held captive as breeding stock, useful only for furthering the human race. The characters in Bird Box must navigate the world blindfolded to avoid eye contact with monstrous entities that, upon being seen, force them to involuntarily commit suicide. In A Quiet Place, Earth has been invaded by extraterrestrial predators with hypersensitive hearing, consigning the human characters to creep around trying — and often failing — to avoid making any noise. In Get Out, the bodies of young black men and women are parasitically occupied by white counterparts, who leach the vitality from their hosts.

Many of these narratives also serve as morality tales: the virtuous, able, alert and tough survive; the immoral, weak and clumsy perish. Watching these films, the viewer is encouraged to adopt a position of superiority and to anticipate the disaster before it befalls a character: I would never make that fatal mistake, we tell ourselves. I would know better; I would survive.

Amid all this feverish post-apocalyptic speculation about the manifold ways humanity might be brought to the brink of extinction, there is one pervasive unacknowledged norm. The protagonists with whom we identify — whose struggles and trials and fears we vicariously experience — are overwhelmingly young. The healthy body is the default. The young have more at stake; their prospective loss is imbued with the poignancy of a life cut short in its prime. The middle-aged are at best ancillary characters, killed off through overconfidence or acts of self-sacrifice for the greater good. And the elderly? The elderly are nowhere to be seen in these brave new worlds. They are invisible. They don’t exist.

Of course, there is a notable exception to this rule of narrative exclusion. Senicide — the killing of the elderly, most often at an age of perceived inutility — stretches back centuries as a fate meted out in literature. The Jacobean satirical play The Old Law (1618–19) by Thomas Middleton and others — in which men are involuntarily executed at eighty and women at sixty — is an early progenitor of what is now an established geronticidal trope within dystopian fiction.

Anthony Trollope’s final novel, The Fixed Period (1882), envisages a future in which euthanasia is mandated after a fixed period; the elderly are shunted off into a college, the Necropolis, for retirement at sixty-five and then execution at 67.5. In Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), the elderly are killed at sixty, then cremated and recycled into fertiliser. In P.D. James’s Children of Men (1992), sixty-year-olds are subjected to a mass drowning called the Quietus. In Christopher Buckley’s Boomsday (2007), baby boomers are offered incentives to commit suicide at seventy. In Lidia Yuknavitch’s The Book of Joan (2017), the execution age is set at fifty; humans are recycled into a water supply for a colony orbiting the Earth on a satellite. In the horror film Midsommar (2019), elders of a cult must commit ättestupa — a ritual suicide by jumping off a cliff, drawn from Nordic folklore — at seventy-two.

It is no accident that the extermination age in these examples hovers around retirement age. Retirement is typically the point at which one is no longer economically productive, and therefore ceases being of value to the community. In many of these examples, the inutility of the aged body is further underscored by its transformation into useful resources such as fertiliser, water or fuel; this commodification underscores the fundamental importance of contributing productively to the community, even after death.

Senicide is, of course, not solely the province of fiction; documented instances exist of various cultures having supposedly killed the elderly through history, including in Sardinia, where women known as accabadoras would bludgeon or suffocate the elderly, and in Japan, where the possibly apocryphal practice of ubasute involved dumping elderly relatives on a mountaintop to die of exposure. In present-day India, in the southern districts of the state of Tamil Nadu, the well-documented phenomenon of elderly relatives being killed by family members is known as thalaikoothal, a practice in which the elderly are given cold oil baths to reduce the body temperature, then fed tender coconut water and milk, prompting renal failure. These overt acts of senicide are supplemented by the decades-old epidemic of “granny dumping” in the United States and elsewhere, wherein elderly relatives are abandoned far from home by family members who can no longer afford their healthcare and who view care giving as overly onerous.

This senicidal thinking is founded on the premise that human worth is aligned to productivity: a concept that stretches back to Plato’s Republic, where Socrates argues that medical treatment and intervention is only appropriate if it allows a productive citizen — Socrates proffers the example of a carpenter — to fulfil his role in the community. When the carpenter ceases to work and contribute productively to the community, Socrates argues, there is no sense in unnecessarily prolonging his life; therefore, medical treatment should be withheld: “No treatment should be given to the man who cannot survive the routine of his ordinary job, and who is therefore of no use either to himself or society.”

In dystopian literary narratives, the ruling generation typically justifies overt violence towards the aged through the lens of economic rationalism: the elderly, according to Margaret Cruikshank in Learning to Be Old (2003), are viewed as burdensome “parasites [who are] expensive to maintain” and consume resources without contributing anything of worth to the community.

Lionel Shriver picks up this theme of the economic burden of unproductive elderly citizens in her 2016 novel The Mandibles, set in 2029 after a market crash devalues the US dollar, consigning families to live in cramped squalor. In Shriver’s future, inheritance impatience is rife, and the elderly are shot en masse as an act of retribution for the crime of having sent the inflation rate soaring because of the cost of their pension benefits.

Yet the elderly are punished not only for perceived economic crimes but for environmental ones, too. Margaret Atwood’s 2014 short story “Torching the Dusties” underscores how easily scapegoating morphs into legitimised violence. “Torching the Dusties” centres on the residents of a retirement community, Ambrosia Manor, who are besieged by a mob of irate protesters who belong to an anti-elder movement, Our Turn. Our Turners burn down nursing homes with their occupants inside while wearing baby-face masks, and see their vigilantism as retribution for the wastefulness and greed of the previous generation.

It is not difficult to see real-world echoes of millennials’ visceral dislike and resentment of baby boomers in Shriver’s and Atwood’s dystopias. This intergenerational hostility has been further underscored recently by “OK Boomer” memes, and accusations such as those made by Bruce Gibney that boomers are a “sociopathic generation” who have “mortgaged the future.”

The eldest of the boomers, now in their mid seventies, will be the next cohort to enter residential aged care, if they haven’t already. While the average age of home-care adoption is eighty for men and eighty-one for women, and the average age of admission to permanent residential aged care is eighty-two for men and eighty-five for women, there is no minimum age requirement for access to aged care, and boomers suffering from early-onset conditions will already be receiving care in one way or another. The most common term used to describe the looming influx of the balance of the boomer generation into the aged care system — “silver tsunami” — likens boomers’ longevity and the associated ballooning cost of aged care to the onset of a natural disaster.

Kurt Vonnegut’s story “Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow” goes further in directly apportioning blame to the elderly for the degradation and depletion of Earth’s resources. Set in 2158, in a world in which a drug called anti-gerasone has drastically extended the lifespan of Earth’s inhabitants, Vonnegut envisages a future in which insatiable pursuit of longevity by the elderly is responsible for nightmarish overpopulation, food shortages and the depletion of natural resources, consigning the remainder of the population to live in squalor and subsist on seaweed and sawdust. While Vonnegut illuminates the cruelty and greed of impatient descendants who try to kill off 172-year-old protagonist Harold “Gramps” Schwartz by sabotaging his anti-gerasone, he also offers a cautionary tale about the perils of failing to gracefully accept one’s mortality. It is desirable to die at an appropriate time, and indecent to live too long.

So it goes.

In truth, the apocalypse has already arrived for Australia’s elderly. We treat older people as a separate and subhuman class, frequently viewing them as a burden on their families, the community and the state. Increasingly, this dehumanisation has taken a corporatised tone; as the elderly exit the workforce, they become a commodity to be mined for profit and dividends by the aged care industry.

The profits posted by Australian aged care providers are directly financed by the government, which contributes the vast majority of the sector’s funding. Commonwealth funding is tipped to reach $21.7 billion in the year 2019–20, which represents 80 per cent of the sector’s total funding. Of this amount, approximately 68 per cent is spent on residential aged care; the rest goes to home-care, home-support and flexible aged care packages. Consumer contributions finance the remaining 20 per cent, either through often exorbitant Refundable Accommodation Deposit bonds, which at the most recent estimate represent a $27.5 billion contribution to providers’ coffers, or through Daily Accommodation Payments, basic daily fees or home-care payments.

Yet in spite of the high proportion of government funding underwriting the aged care industry, there is little transparency about how much providers spend on primary care. Reforms ushered in by the Aged Care Act 1997 mean that providers no longer need to demonstrate that the funding they receive via the Aged Care Funding Instrument is spent on care; rather, expenditure of taxpayer funds is entirely at providers’ discretion, and they don’t need to return any unspent monies to the government. The correlation that one might expect to see — higher funds equating to higher expenditure on care — doesn’t always play out. In 2017, Bupa’s funding from both the government and residents’ fees increased, yet it paid almost $3 million less to employees and suppliers.

Compounding this lack of transparency are the financial reporting requirements themselves. While three providers — Regis, Estia and Japara — are ASX-listed entities and therefore subject to stringent reporting requirements to ASIC, many other providers can file limited financial statements under the reduced disclosure requirements set by the Australian Accounting Standards Board, meaning there is minimal scope for scrutiny of their financial practices. While not-for-profit providers represent 55 per cent of all residential aged care providers and two-thirds of home-care providers, the ever-increasing share of for-profit providers, especially in the residential sector, signals that aged care is big business in Australia.

Australia’s top six for-profit aged care providers — Bupa, Opal, Allity, Regis, Estia and Japara — received $2.17 billion in government subsidies in the 2017 tax year while also posting significant profits and using aggressive tax-minimisation strategies such as discretionary trusts. Bupa, Australia’s largest private aged care provider, made a profit of $663 million in 2017, 70 per cent of which ($468 million) came from government funding. Opal, Australia’s second-largest private provider, posted a total income of $527.2 million in 2015–16, 76 per cent of which came from government funding, yet it paid a mere $2.4 million in tax on a taxable income of $7.9 million.

The foreign-ownership structures of several of the major players — Bupa is headquartered in the UK, and Opal belongs to a parent company in Singapore — have further enabled providers to pursue aggressive tax-minimisation strategies. In 2019, after a ten-year dispute with the Australian Taxation Office, Bupa paid $157 million in restitution for the alleged practice of “thin capitalisation” — that is, using high-interest offshore debt to artificially reduce its taxable income. The abolition of probity requirements by the 1997 Aged Care Act has further eroded the government’s capacity to assess, scrutinise and regulate ownership of aged care providers.

Yet at the same time that private providers are posting huge profits and paying minimal tax, the standard of Australian aged care is cratering. Most sensationally, Bupa posted a $560 million profit in 2018, the same year it made headlines when more than half of its aged care facilities across Australia were failing basic care standards, and 30 per cent were deemed to pose a serious risk to the health and safety of residents. With approximately 6500 frail and vulnerable residents spread across its seventy-two facilities, Bupa is now considered “too big to fail” and remains open in spite of repeated sanctions and scandals. Clearly, in the absence of strict regulation and public reporting, privatisation has only served to enable and entrench abuse and negligence, rather than to drive poor providers out of business.

The monumental failures of Australian aged care have been in plain view for a long time, well before prime minister Scott Morrison called the royal commission in 2018. Over the past decade, seventeen reviews and inquiries into the aged care sector have been handed down, many of which have passed with little media interest and the implementation of few or none of the proposed reforms.

To take one prominent example, the 2017 Carnell–Paterson Review of National Aged Care Quality Regulatory Processes — intended in part to probe how horrific abuse at the Oakden nursing home in South Australia could occur while the facility remained fully compliant and accredited — made ten sweeping recommendations to achieve tougher regulation and greater transparency within the aged care sector. These included the creation of a public register of the outcomes of complaints and investigations, the implementation of a public star-based rating service to track provider performance, increased powers for the complaints commissioner, and the adoption of clearer clinical-care measures in the assessment and accreditation processes.

More than two years after these findings were handed down, only a handful of aged care reforms have been passed, and none of the recommendations specifically aimed at achieving tougher regulation and greater public transparency have been implemented. Many have not even been considered. The government cites statutory secrecy under the Aged Care Act, Commission Act and Privacy Act as its justification for not making the reporting of complaints about provider performance more transparent. But the undue influence of peak bodies — which represent the interests of providers and vehemently oppose transparency measures — has also decreased the government’s appetite for reform. The government’s hands-off, market-driven approach to aged care is grounded in economic rationalism, callously ignoring the inconvenient fact that the physical and mental frailty of aged care recipients, combined with the dearth of public information about provider performance, preclude aged care “consumers” from exercising meaningful “choice.”

Perhaps most frustratingly, many of the issues plaguing the sector today were foreseen and thoroughly canvassed more than twenty years ago during the Senate inquiry that preceded the passage of the 1997 Aged Care Act. The removal of staff-to-patient ratios was predicted to result in compromised care, and experts also predicted that the accreditation process was inadequate to stop this from occurring. In the two decades since, review after review has exposed chronic understaffing, inadequate regulation and accreditation, the lack of transparency, and the poor care outcomes in the sector — and in each instance, successive governments of both political persuasions have responded with piecemeal reforms or no reforms at all.

This government inertia has played out against a backdrop of escalating failures in the sector, including a 170 per cent increase in serious risk notices in the year prior to the royal commission being called, and a 292 per cent increase in serious noncompliance. The standard of care in residential facilities has deteriorated unabated: between 2003 and 2013, there was a 400 per cent increase in preventable deaths in Australian aged care facilities from choking, falls and suicides. In 2017–18 alone, there were 3773 reportable assaults, including 547 reportable sexual assaults and rapes. These statistics represent a fraction of the true number, because they only account for incidents in which the perpetrator does not have an assessed cognitive or mental impairment. Given that more than half of aged care residents suffer from dementia, the actual assault figures are likely to be significantly higher.

In addition to these extreme instances of neglect, mistreatment and abuse, baseline levels of primary care are also shocking in both residential and home care. In the royal commission’s interim report, commissioners Richard Tracey and Lynelle Briggs noted a voluntary survey filled out by 1000 aged care providers that cited 274,409 self-reported instances of substandard care over a five-year period, including 112,000 instances of substandard clinical care and 69,000 incidents of substandard medication management. Considering that this survey was undertaken by fewer than half of Australia’s 2695 aged care providers and that there are only approximately 240,000 aged care residents in Australia today, along with approximately 118,000 home-care package recipients, it is evident that Australian aged care is failing on an industrial scale. And as Australia’s population rapidly ages — the number of Australians aged seventy years and older is projected to almost triple over the next four decades, reaching seven million by 2055 — the size of the problem will only grow exponentially.

Indeed, as the commissioners noted, if population trends identified in 2014 hold true, “more than a third of all men and more than half of all women will enter residential aged care at some time in their lives.” The difficulty the sector faces in attracting and retaining qualified staff, combined with the high rates of turnover and low skill base of the workforce, places even more pressure on providers’ capacity to accommodate these ever-increasing numbers. And while some providers are posting colossal profits, others are not making any profit at all. In 2019, the Aged Care Financial Authority reported that approximately 44 per cent of residential aged care providers are operating at a loss, and many are at risk of closure: factors that are only likely to wreak more chaos in the sector in the future, and produce more catastrophic outcomes like the recent shock closure of Earle Haven.

The sector’s failure to provide safe and dignified care is compounded by inadequate regulation; too often, providers are asked to “self-assess” or interpret vague and elastic guidelines rather than conform to hard and fast quantifiable standards. The commissioners also noted in their interim report that the regulatory regime administered by the newly formed Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission is “unfit for purpose.” The lack of effective oversight means that families often turn in desperation to installing hidden CCTV cameras to confirm their suspicions of abuse and neglect.

As the distressing footage screened on the ABC’s two-part Four Corners investigation, Who Cares?, in September 2018 and subsequent news bulletins have shown, our most vulnerable citizens are being slapped across the face by abusive carers, injured through “rough handling” — a dehumanising euphemism that anywhere other than an aged care facility means “assault” — raped and sexually assaulted in their most vulnerable state, drugged unnecessarily, cruelly restrained, and left to sit in distress in their own faeces and urine. There have even been several cases of aged care residents infested with maggots, including a dying woman in palliative care who was found with maggots living inside her mouth. Much of this abuse and neglect would never have come to light without the determination of relatives and advocates.

While media coverage of aged care has been dominated by the failures in residential care, the home-care sector has not performed any better. Due to a near total lack of regulation of home-care providers, there has been rampant rorting, including exorbitant administration fees levied that, in some cases, effectively halve the package for the recipient, as well as neglect, abuse, assault and even rape of older Australians in their own homes. The issues of unskilled, unqualified and unscrupulous staff in residential care also extends to home care: in March 2019, the royal commission heard from a health department witness that eight out of ten applicants applying to provide home-care services were unqualified “bottom feeders” who view the provision of care as nothing more than a “business opportunity.”

Even accessing care in the first place is proving increasingly difficult for older Australians. Thousands die each year while waiting for the Home Care Packages, or HCPs, they need, while others endure extraordinary time frames for their HCPs to come through. In the financial year ending June 2018 alone, more than 16,000 people died while waiting for HCPs, and as of June 2019, 119,524 people were languishing on the waiting list. The royal commission reported that actual wait times are significantly longer than the public guidelines cited on the My Aged Care website, which provides an estimate of twelve-plus months as the expected time for levels 2–4 HCPs.

The stark reality, according to the health department, is that for those requiring the highest level of support — a level 4 HCP — the mean waiting time is twenty-two months, and a quarter of those people will wait three years to receive care. The consequences of this logjam, the commissioners note, are dire, including “inappropriate hospitalisation, carer burnout and premature institutionalisation.” The federal government’s response to the royal commission’s interim report was to announce funding for a further 10,000 packages, which represents less than 10 per cent of the number required to clear the waitlist.

While the royal commission has played a valuable role in exposing the policy failures that have wrought the current state of affairs, as well as the shocking scale of the endemic abuse and neglect across the sector, it is fair to say that the concomitant outrage has been muted. Real-time media monitoring demonstrates 300 per cent less media coverage of the aged care royal commission than there was of the banking royal commission. It is difficult to imagine the mistreatment of any other vulnerable group being met with such widespread indifference. And the apathy and cognitive dissonance of politicians — many of whom, like aged care minister Richard Colbeck, who is sixty-one, are not far from retirement age and may be facing entry to the aged care system far sooner than they think — are profound.

As someone who cares deeply about this issue, having given evidence to the royal commission about the sadistic mistreatment my father has been subjected to in aged care, I admit I am baffled by this lack of empathy for older people. It is a failure that flies in the face of the obvious: as Proust says in Time Regained, “life makes its old men out of adolescents who last many years.” We are all ageing every day; it is the one activity that every human being on earth is doing continuously.

If we are lucky, we too will one day grow old. Old age is, ultimately, what we are supposed to aspire to.

The utopian fantasy of a comfortable retirement — years replete with travel, golf, walks on the beach, and bouts of grey nomadism underwritten by a fat super account and a paid-off mortgage — is the enduring (if increasingly unobtainable) Australian dream. Even the faintest suggestion from Labor that it might tinker with franking credits and therefore impinge on the lifestyle of retirees was enough to swing a federal election. Yet in spite of all this aspirational saving and leisure planning, we devote no time to contemplating the realities of ageing or the possibility that the frailty and vulnerability that often accompany old age may one day arrive for us. The one way we cannot imagine ourselves spending our final years is in an aged care facility. It is not an exaggeration to say, as Simone de Beauvoir once did, that “old age fills [us] with more aversion than death itself.”

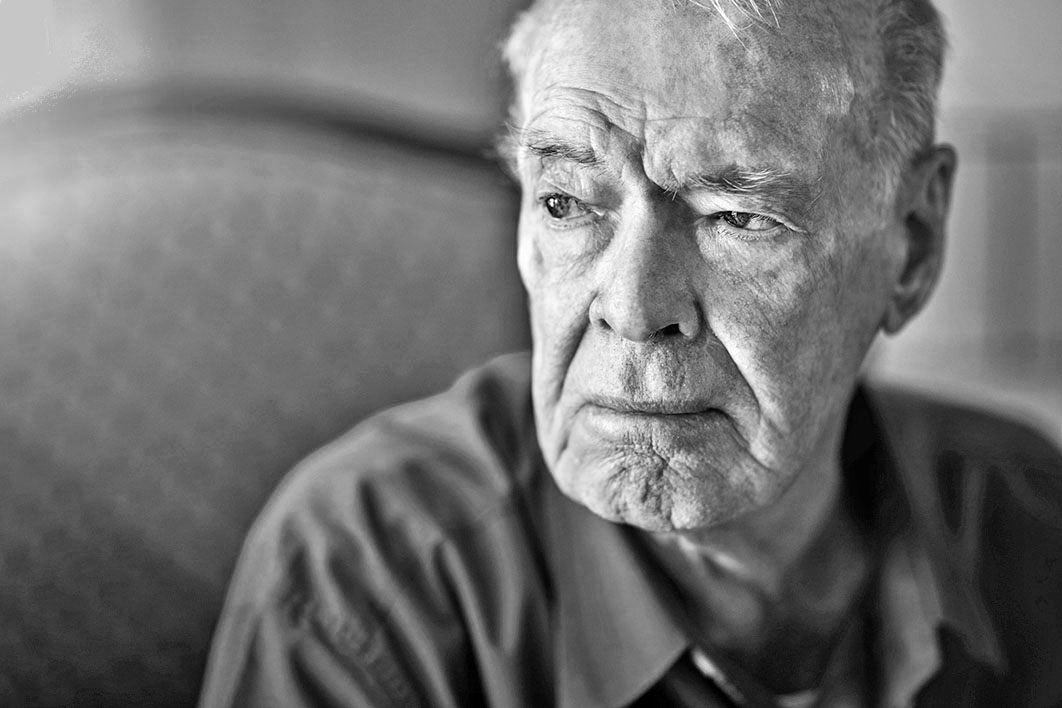

Perhaps this is because, for all of our utopian and dystopian imagining, the reality of ageing is too frightening to contemplate. When I think about my father — a man who was once a livewire, a brilliant scholar and mineral metallurgist, and who is now consigned to a wheelchair with Parkinson’s disease, dementia, incontinence and a host of other complaints too numerous to list — his loss of selfhood, independence and agency overwhelms me.

My father relies on carers for the basic actions that so many of us take for granted: they brush his teeth; they toilet, shower, dress and feed him; they hoist him in and out of his wheelchair. He frequently hallucinates, finds himself lost mid-sentence, suffers from sudden panic attacks when he loses his bearings, and often doesn’t recognise his own bedroom. He cannot co-ordinate his movements to even pick up a cup and drink from it. He has difficulty swallowing due to his Parkinson’s and is at constant risk of choking: a common cause of death among Parkinson’s sufferers. His personality has changed. His body and mind are no longer in sync; he lives in continual frustration and confusion. He will spend the rest of his life wandering lost in a wilderness of his mind’s own making. The French philosopher Catherine Malabou, writing about destructive brain plasticity in Ontology of the Accident (2012), best describes the state my father lives in: “Between life and death,” she says, “we become other to ourselves.”

The fear of becoming other to ourselves — of not knowing who we are, of losing agency and control — is so acute precisely because it threatens the very foundation of selfhood. We spend our childhood and youth striving towards self-sufficiency and independence; the notion of that independence eroding is terrifying. While I am bereft for my father and the precarious, vulnerable state he is consigned to, I resist imagining myself in his place, even though I know intellectually it is possible the same things may happen to me. The very thought produces an overwhelming existential terror in me, a visceral fear.

So what would it mean to admit to myself that one day I may become old? It would mean accepting that my mind, which I prize above all things, may flicker out like a tired filament, that I may not be able to keep pace with the conversations and arguments I take for granted, that I may forget the people around me, that I may forget who I am, my very name. I may not know where I am. I may become vulnerable — utterly vulnerable — to strangers. That, worse, I may lose control over my body, which may rebel against me in humiliating ways; that I may not be able to walk, or speak, or even swallow. I may become diminished in the eyes of others. There may come a time when nobody listens to what I say because I no longer make any sense. I may no longer be able to taste food, as dementia sufferers cannot; I may no longer be able to see, or hear, or smell. My world may become blanched of colour, texture and joy. It is hard to imagine that a life without all those powers and pleasures is any kind of existence at all, but I am haunted by the knowledge that this litany of privations is exactly how my father experiences his days.

It is tempting to embrace the consolatory fantasy that those with diminished cognition don’t remember or can’t understand the full weight of what is happening to them — but the painful truth is that, bereft of memories of the past or the prospect of the future, my father only experiences an unceasing present tense. His impossible fate is to inhabit his every remaining minute in the throes of his needs, his discomfort, his hunger, his longings and his frustrations without the refuge of nostalgia or the prospect of change. Above all, to imagine becoming old is to admit a fundamental truth that threatens me viscerally: I may one day become worthless to others. I may become invisible.

But my father’s frailty and diminished quality of life are not the only things I must try to imagine: I owe it to him to also try to comprehend the negligence, neglect and abuse he has experienced in his aged care facility, which formed my testimony to the royal commission. Dad sustained a broken hip and was lying on the floor for God knows how long before someone found him, because there was nobody to take him to the bathroom. He suffered six broken ribs — including two that went untreated and were partially healed by the time they were found by a radiologist — from two other falls incurred for the same reason. He has been given contraindicated medication that effectively left him without his Parkinson’s medication for months. He has been frequently left unclean, without his dentures or his glasses, or without a cup of water within reach. He has suffered numerous injuries and infections that have gone undiagnosed and untreated.

Most unforgivably of all, he has been deliberately abused and neglected by a malicious carer, who left him in soiled incontinence pads for hours, who shut the door on him and told other staff he was sleeping when he was awake and desperate to be showered, who taunted him and told him to get his own nappies out in the hall, and who pushed his wheelchair away from his bed on purpose, leaving him immobile. When I try to imagine myself in my father’s place, I can only begin to speculate about his emotions — fear, despair, sadness, impotence, helplessness — before I’m overcome with grief and rage.

It would be destructive, perhaps even madness-inducing, to live with the continual awareness of our mortality. We go to extraordinary lengths to repress our awareness of death; this repression is a protective mechanism that likely serves an evolutionary function. The poet Philip Larkin described this repression in “Aubade,” his great contemplation of death, as the mind “blank[ing] at the glare.” To live in constant terror and awareness of death is no life at all. Yet we rarely interrogate the cost of the fantasy of our own immortality. As Ernest Becker says in his extraordinary work The Denial of Death (1973), man literally drives himself into blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of his situation that they are forms of madness — agreed madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.

Among the most destructive forms of shared madness are our collective fantasies about the end of life. I have heard these same stock fantasies from my friends, colleagues, family members and acquaintances so often that I have even started to catalogue them: they are varieties of magical thinking, delusional and destructive because they stand in the way of genuine concern and understanding for the elderly. These fantasies also hamper our capacity to imagine our own futures realistically and contemplate our own far more likely fates as recipients of some form of aged care.

The most common fantasy I hear when I mention aged care is that of voluntary suicide. “I’ll kill myself before I ever go into a nursing home,” people tell me nonchalantly: a farcical pronouncement that presumes that they will be well enough to kill themselves before life gets bad enough that they need to. Nobody does this, and nobody will, but it is a powerful and enduring fantasy because it suggests we will exert agency at the precise moment when we have none. It is also something my father used to say repeatedly; of course, he, like everyone else, never really meant it.

People my own age (late thirties/early forties) often buy into what I call the commune fantasy, in which a group of friends age and die together, chipping in to buy a common property to live in, pooling resources and paying for carers together like a geriatric co-op. This fantasy presumes, of course, that all the friends in the group will have the same care needs at the same time, will sell their assets simultaneously, will be able to oversee their own care needs even if those needs include cognitive impairment or dementia, and will somehow be able to afford the astronomically expensive medical equipment used in aged care facilities, including hoists, pneumatic mattresses and a twenty-four-hour nursing and caring staff. Essentially what someone means when he or she tells me about their utopian aged care kibbutz is this: I will build my own private nursing home from scratch. This, for all the obvious reasons, also never happens — but it is a powerful fantasy precisely because it suggests that in our time of greatest need, the tribe will be there for us.

Then there are the technological optimists, who believe that by the time they reach old age, the conditions that the elderly suffer from now will have been eradicated by science, or a fountain of youth will render these problems moot. This is, of course, a profoundly narcissistic approach — what about all the elderly suffering in aged care in the meantime? — as well as a ludicrous one.

People also fantasise about dying peacefully in their beds, although as our life expectancies increase without a commensurate extension in our quality of life, we are more likely to become institutionalised than previous generations, rendering this scenario less and less likely.

And finally, there are the fatalists who joke darkly about how we won’t know any better because we’ll all be drooling in wheelchairs parked in front of a television. I don’t get the sense that those who say this really believe it. Rather, they say it flippantly, jokingly, although the subtext is more sinister. The system’s broken and nothing can be done to fix it. Why bother trying?

My blood thunders when people repeat these fantasies to me, because ultimately such magical thinking begets apathy and inertia. If we refuse to imagine what it is like to age — and accept that one day we, too, will become old — then nothing changes and the appalling status quo will continue. Our collective failure to imagine the lives of the elderly is the primary obstacle in the way of genuine empathy: an empathy that should be predicated on the acknowledgement that one day we will join their ranks. If we spent as much time contemplating the realities of the end of life as we do fictive dystopias and the extermination of humanity, we would have the reforms we need in aged care, and greater human rights and dignity for our elders.

In the meantime, the shambolic, diabolical state of aged care remains a horror each successive generation seems bent on discovering for itself, when it’s far too late. More’s the pity. As Larkin wrote: “Most things may never happen: this one will.” •

This essay is republished from GriffithReview 68: Getting On, edited by Ashley Hay (Text), where a referenced version can be found.