British India, White Australia: Overseas Indians, Intercolonial Relations and the Empire

By Kama Maclean | UNSW Press | $39.99 | 320 pages

Australianama: The South Asian Odyssey in Australia

By Samia Khatun | University of Queensland Press | $34.95 | 320 pages

Indian-origin Australians are the fastest-growing group in the population, their numbers catching up with those of Chinese descent. Canberra, meanwhile, is in the midst of one of its periodic rediscoveries of India, this time as a potential economic and strategic counterweight to China. The timing couldn’t be better for two books that explore Australia’s early relations with what we now call South Asia and highlight pitfalls to be avoided this time around.

Before Australia finally shrugged off the White Australia policy in 1973, South Asians were a small minority — a little over 5000 at their peak in the 1890s, as against 29,000 or so Chinese. In scattered numbers on the margins of settlement, they incurred less of the resentment that sometimes erupted into murderous anti-Chinese riots.

Many of these South Asians were here because they had been invited: recruited by colonial authorities and businessmen from the 1860s to build and operate the networks of camel transport that serviced remote mines and grazing runs. They also had the advantage of being British subjects, if second-class ones.

In asserting this imperial identity, according to historian Kama Maclean, Indian Australians separated themselves from “Asiatics” and “Orientials” with some lasting effect. “It is curious that in Britain, many Indian communities have come to identify and be identified as ‘Asian,’” she writes. “In Australia, Indians have largely been thought of as an entirely separate category, not necessarily Asian at all.”

But they suffered calumnies and bureaucratic obstruction enough, as historian Samia Khatun shows in her case studies. And the official exclusion after Federation, when they were lumped in with “Asiatics” under the Immigration Act, was an immense and long-lasting insult to the educated classes of the entire subcontinent, even those who never thought to come here.

White nationalism in the settler colonies was the fly in the ointment London was using to try to soothe India from the mid nineteenth century on. After suppressing the great Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, Queen Victoria had proclaimed that all subjects of the empire would be treated equally. Colonial secretaries chided premiers in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa over racial exclusion, but the admonishments were generally batted off as humbug on the part of an empire that embodied a deep racial hierarchy.

Among Australians, images of the subcontinent derived from the writings of Rudyard Kipling, who visited Sydney, Melbourne and Hobart in 1891, and from romantic writings about fabulously wealthy maharajas and sultans, the mystical yearnings of Theosophists, and the opinions of resident “old India hands.” The term “Hindoo” was used synonymously with Indian, emphasising “otherness” and “heathen rituals.” Even the few senior politicians with a deeper knowledge of India, among them Alfred Deakin, upheld the White Australia policy.

But some softening of the policy did occur quite early. Persuaded by a new governor-general, Lord Northcote, who had come straight from governing Bombay, the Watson government amended the Immigration Restriction Act in 1904 to let Indian merchants, students and tourist travellers enter for up to twelve months.

Not many took advantage, and deportations of Indian traders like Mool Chand (in his case for having entered Australia under false pretences) raised periodic outcries in India. Meanwhile Deakin, as external affairs minister, was trying to get more Australians into the elite Indian Civil Service, arguing that hardy Australians were just the thing India needed to get organised and open up new fields of development. “In this, Deakin seemed to be imagining an India of mutiny novels and Boy’s Own adventures,” observes Maclean. Indian newspapers saw it as a double standard: let us in, but you stay out.

After diggers fought alongside Indian soldiers in Gallipoli, Palestine and France during the Great War, postwar Australian views moderated a little. Norman Lindsay’s South Asian character “Chunder Loo,” who featured in advertisements for Cobra Boot Polish, was transformed into an amiable, subservient comic figure present at great events. Australian prime minister Billy Hughes and his British counterpart David Lloyd George might have cursed each other in Welsh at times, but at the 1921 Imperial Conference Lloyd George pressed Hughes to agree on a compromise — keep your external barriers, but remove discrimination for those inside — acceptable to the Indians.

As much as Hughes had fought at Versailles against a racial equality clause in the League of Nations charter, he also worried about the growing power of the United States, which was drawing Canada closer, and the unrest in Ireland, Egypt and India. It all threatened to break up the empire and threaten Australia’s “lifeline” to Europe.

So imperial duty saw British-Indian residents of Australia — now about 2000 in number — given the vote and the pension. The remnant of the earlier, larger population most widely recalled are the itinerant turban-wearing pedlars who roamed inland settlements in horse-drawn carts, bringing haberdashery and household implements along with a touch of exotic colour to isolated households.

As nationalism deepened in British India, writes Maclean, settler colonies like Australia “inadvertently presented a third front against which the British in India and in London could imagine and claim to be championing Indian causes.” The Balfour Declaration of 1925, which gave equal status to all Britain’s dominions — Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa and the Irish Free State — let London off the hook: it could say it had no control over their immigration policies.

Continuing discrimination through the 1930s and 1940s also had the unintended effect of encouraging India’s leaders to reject British offers of eventual dominion status. India would always be a second-class member of the empire, said Jawaharlal Nehru, the man who would be India’s first prime minister. The Bank of England had brought Australia to near bankruptcy in the Great Depression; imagine what it might have done to an Indian dominion.

With the fall of Singapore, India became even more of a lifeline for Australia, and the Indian nationalists had Churchill over a barrel. Eventually, two years after Japan’s surrender, London agreed to India’s independence. Prescient Australians had seen this coming. In September 1942, external affairs minister H.V. Evatt had said that Australia “looked forward to the people of India becoming a truly self-governing nation,” with the rider that it should still be loyal to the King. Canberra and New Delhi exchanged high commissioners during 1943–44.

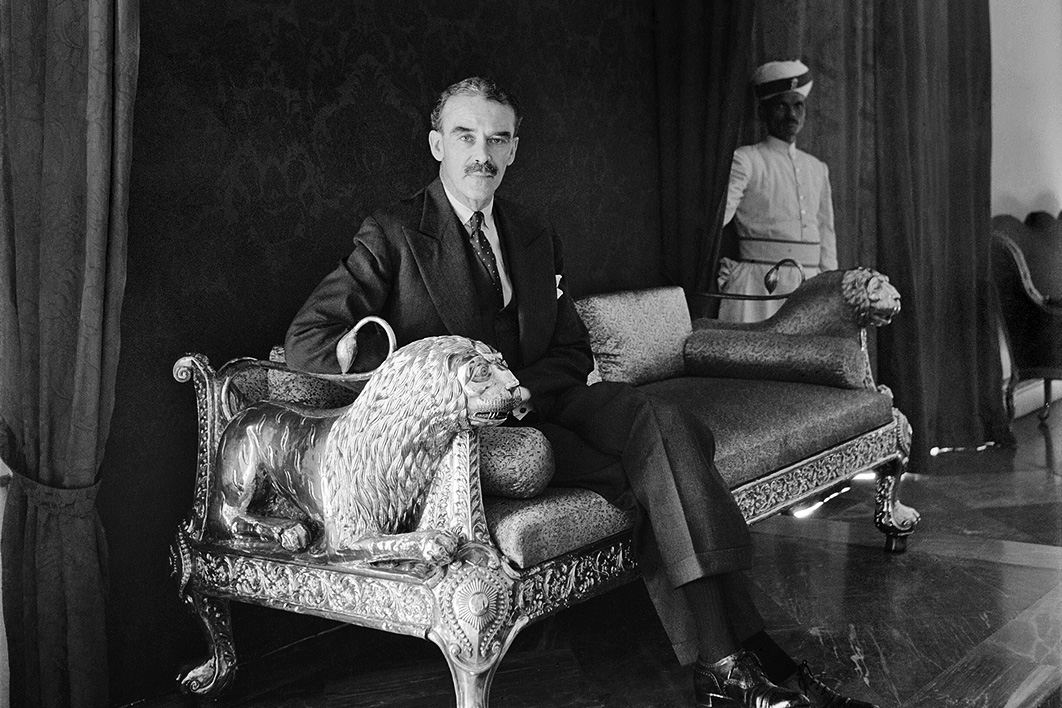

The appointment of R.G. Casey as governor of Bengal in December 1943 put an Australian at the centre of one of the second world war’s most tragic episodes, the famine that gripped this frontline state during 1943–44 and killed some three million people. Maclean shows us how Australians became aware of the famine through church, business and personal correspondence that got around wartime censorship, and pressured Canberra to release its stockpiles of wheat. The government was prepared to do so if the War Cabinet in London would release the necessary ships. Only in February 1944 did large shipments begin belatedly flowing.

Somehow the glamorous couple, Casey and his wife Maie, floated above this misery. After Casey resigned as governor in June 1945 in order to return to Australia and enter politics, he wrote An Australian in India, a book that took a relatively sympathetic view of Indian nationalism, and distanced himself from the British administration. As an Australian, he claimed, he had gone to India “with no imperial past.”

Casey argued that once it was explained that the White Australia policy was based on economic, not racial, grounds it was “generally accepted” in India. But when the departing British asked Australia to take in some “Anglo-Indians” — the mixed-race and generally well-educated and prosperous children of empire — Canberra agreed only to those who were “predominantly of European blood.”

As external affairs minister for most of the 1950s, Casey shared with his prime minister, Robert Menzies, a somewhat distant relationship with Prime Minister Nehru. According to Maclean, Casey was arguably closer to Pakistan, which was drawn to the Western side as the cold war set in. He continued to play down the White Australia policy rather than try to change it, and urged the Australian press to stop using the term.

And so it went on — and so, to some extent, it continues. Our leaders are puzzled why Indians are so “hypersensitive” about race; they tend to assume all experiences of empire are the same. Multiculturalism has comfortably located racism in the past; events like the Cronulla riot of 2005 and the attacks on Indian students in 2010 are seen as aberrations.

“Many note that Australian attempts to engage with India have gone unrequited,” Maclean says. “Few have tried to appreciate why this might be the case.” Still, the Indian population in Australia grew 30 per cent over 2016–18. Whether Australia can overcome its past is still an open question, she says, but “it is clear that a redefinition of ‘Australian’ is under way.”

Samia Khatun isn’t so sure. She sees cant in how we welcome well-off and highly skilled South Asians, patting ourselves on the back for our openness, while treating undocumented arrivals by boat, many from the same region, so shamefully.

Khatun’s book focuses on the South Asians (having been born in Bangladesh, she is careful to use that term) who came to Australia during that early half-century window. This is an important, eye-opening exploration of their world and its connections, bringing into vivid centrality the “Afghan” cameleers who are auxiliary figures on the periphery of events in mainstream history.

Her “Book of Australia,” as the title translates, began as a doctoral thesis in history at the University of Sydney, and still reads like that in places. But between the thickets of Foucauldian and other theoretical analysis of the “epistemic arrogance of modernist paradigms of thought” is a fascinating detective story.

It began when she read of “an old Quran” found by local historians in the corrugated-iron mosque in Broken Hill. She travelled there, and found the book was actually a compendium of eight books of Sufi poetic legend titled Kasasol Ambia (Stories of the Prophets). How did a book of poetry in Bengali published in 1895, written to be read aloud, come to Broken Hill, when most of the cameleers were from the northwest of undivided India and Afghanistan?

Her quest to find out took her to Calcutta and its busy publishing hubs, to encounters with an irascible scholar of old texts, and to the stories of the men and women who might have picked up the book in Calcutta on their way to Australia.

We learn about characters like Khawajah Muhammad Bux, who became a wealthy Perth-based trader before retiring to Lahore in the 1920s, where he built a mosque and a girl’s school in what became known as Australia Chowk (Australia Bazaar); Bux’s son later founded the one hundred–branch Australasia Bank, now part of Pakistan’s big Allied Bank.

And Hasan Musakhan, a brilliant scholar from Karachi who won a scholarship to Bombay University and then joined a big camel operator in Australia. A follower of the Ahmadi branch of Islam (later declared heretic by the mainstream), he married Sophia Blitz from a German-Jewish family in Adelaide and became active in court cases contesting discriminatory application of the law and a writer of letters to newspapers.

Khatun recounts marriages and other encounters between South Asian men and white and Aboriginal women; brides and wives brought out from India, some in purdah, some not; and jealous shootings and elopements. This richly detailed account culminates in her journeys with descendants of the Aborigines who mixed with the Abigana (Afghans) along the camel routes and railway lines that penetrated inland to places like Marree and Oodnadatta. In this sandy country, she coaxes out the background to some of the perplexing incidents in the written record.

Khatun is not very forgiving of settler Australians and “monolingual” historians attracted to facts and progressive narratives rather than the imagined worlds and dreams she taps into. She has a wonderful ability to capture the landscapes of inland Australia and make its “marginal” people central. In showing us what has been under our noses, Australianama is as good as Bruce Chatwin’s The Songlines, if not better. •