Dunera Lives: Profiles

By Ken Inglis, Bill Gammage, Seumas Spark and Jay Winter with Carol Bunyan | Monash University Publishing | $39.95 | 512 pages

Almost three years after his death, it remains difficult to convey the esteem in which Ken Inglis (1929–2017) is held by his colleagues in the Australian historical profession. While his name remains less recognisable to the public than several of his contemporaries, Inglis has strong claims to be considered the leading Australian historian of his generation. He managed to combine the roles of research historian and public intellectual seamlessly — and without becoming a media tart chasing tabloid notoriety, political patronage or C-list celebrity status. None of these baubles — sometimes attractive to academics with his talents — seemed to have had the slightest appeal to him.

Inglis achieved both national and international eminence, and acknowledged that he had lived a privileged professional life. But when the choice was between defending the weak or barracking for the strong, he never had to spend any time pondering which side to take. One of his early books, The Stuart Case, along with his journalism on the same subject, probably helped save the life of an Aboriginal man accused of raping and murdering a child in a society that did not, and could not, give him a fair trial. Inglis thought it more likely than not that the accused man had done it, but that did not hinder his desire for justice to be dispensed fairly.

Rather than passing the middle years of his career enjoying the pleasant life of a professor of history in the nation’s increasingly comfortable capital city — a life to which his talents and achievements had given him entree at a still-young age — he went to Port Moresby to help make a university and a nation. He would eventually serve as vice-chancellor of the University of Papua New Guinea, before returning to the Australian National University as a research professor in the mid 1970s.

Inglis’s own scholarship was formidable, ranging over the history of the media — he wrote two major histories of the ABC — religion, national days and celebrations, colonial social life, and the social and cultural history of Australians at war. He was the originator and leader of the massive, multi-volume bicentennial history project, Australians: A Historical Library.

His major interests were less fashionable in their day than they have become, a marker of both his foresight and his influence. It was in the field of war history, especially through his groundbreaking work on memorials, that Inglis acquired an international reputation and perhaps also exercised his most enduring influence on Australian public culture. He was a key figure in Australia’s rediscovery and reinvention of Anzac.

This was all delivered in elegant but unpretentious and accessible prose that served as a constant reminder that Inglis had early aspirations to become a journalist. He was a cautious, modest scholar despite his great gifts, or perhaps because of them. He knew that there was always much more to learn. I may be permitted, I think, to use language that would have been familiar enough to Inglis who, as I did forty years later, grew up in Melbourne’s northern suburbs. He didn’t have tickets on himself.

And so why did he turn to the history of the 2800 men, women and children who came to Australia in September 1940 on the Dunera, from England, and the Queen Mary, from Singapore, as the final historical project of his life?

As his collaborators explain in Dunera Lives: Profiles, Inglis offered several explanations for his decision. This volume and its predecessor reveal how the lives of some of the men of the Dunera intersected with his own at various points in his life. Franz Philipp, the art historian, tutored the young Inglis at the University of Melbourne and, after recognising his ability in an essay on Machiavelli, asked him, “Why not consider following an academic career?” Later, Inglis inevitably had much to do with Henry Mayer, the Sydney University politics professor, not least through their common academic interest in the media. He shared a Canberra suburb with the retired diplomat and academic Klaus Loewald.

A seventeen-year-old Fritz Lowenstein (second from the right in front row) on a school trip to Bucknow, east of Berlin. Courtesy of Monica Lee Lowen and Jocelyn Lowen

Inglis’s collaborators on this project came round to the view that Inglis turned to the Dunera as a subject out of “the desire of a modest man to tell the story of a chapter of his early life without writing about himself.” This looks right, and certainly in character. The stories of the Dunera and Queen Mary also gave Inglis the chance to research and write history of a kind with which he was most comfortable. Both volumes — this one and its lavishly illustrated companion, published in 2018 — are essentially biographical, and Dunera Lives: Profiles uses the stories of eighteen of the internees (as well as of two other remarkable men, Captain Edward Broughton and Julian Layton, closely connected with the episode) to tell the larger story of the Dunera.

In doing so, Inglis tells a story of the twentieth century, the era that he himself lived through and that formed the subject of most of his writing. The history of this century, his collaborators explain, seemed to Inglis “more disturbing and bleaker than it was ennobling or enlightening.” While no doubt a fair summation of Inglis’s views, this book is also about the lives that the remarkable Dunera affair would subsequently make possible. It is no tale of woe.

Inglis was keen to avoid the hagiography to which the Dunera story has sometimes seemed prone, but there is much that is ultimately uplifting about the stories told here. The internees have come down to us in collective memory as “The Dunera Boys” — all somewhat Peter Pan-ish — thanks largely to the power of television and of one of that vast number of historical miniseries that graced our screens in the 1980s. Much mythology clings to them. They were Jewish. They were intellectuals and artists. They transformed Australian life.

There is some truth in each of these impressions. Many of those interned by the British authorities and sent to Australia on the Dunera in the wake of the fall of France and the Low Countries in mid 1940 were indeed Jews, although not all; and many of the Jews did not practise their religion or observe Jewish customs. Some conformed to the model of what Trotsky’s biographer Isaac Deutscher called a “non-Jewish Jew.” Few were devout. For a good many, their “Jewishness” was a function of Hitler’s racist lawmaking rather than an identity that was meaningful to them.

Quite a few were intellectuals, but there were about 2000 Dunera internees all up, and most clearly were not. A few internees — such as Leonhard Adam, author of Primitive Art (1940), and the Bauhaus artist Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack — were already significant figures in their fields when they were arrested and interned. Others would soon achieve eminence: by the late 1940s Hans Buchdahl, the theoretical physicist, was attracting the praise of Albert Einstein for his work in Hobart on general relativity.

The Australian camps in which they spent the early part of the war hosted a vibrant intellectual and artistic life behind the wire. The Collegium Taturense — at Tatura internment camp — offered lectures in a wide array of subjects, an average of 113 per week at one stage, given by twenty-three lecturers to 700 students. There was sufficient expertise within the camps to prepare internees for matriculation to the University of Melbourne.

Did the Dunera internees transform Australian life? Even to ask the question embodies the misconception that they made their life here. Most, in fact, did not: about 1300, or two-thirds, left Australia. But for some who went to live elsewhere, the threads were not entirely severed. Klaus Loewald, a US diplomat posted to Vietnam, became disillusioned with his adopted country and later took up an academic post in the history department at the University of New England in Armidale.

In retrospect, these men look like an advance guard for the massive postwar emigration from Europe, even if, like the convicts who founded white Australia, they were “unwilling emigrants.” They brought European sophistication and style to a country that was still meat, bread and three veg. No doubt that was part of their appeal to young Ken Inglis, the product of an Anglo-Australian lower-middle-class upbringing in Melbourne.

Dunera Lives does not aspire to be representative; indeed, it is clear that the biographies are not. “You hear all about the professors and doctors,” complained Roy Thalheimer, “but not about the taxi drivers.” Thalheimer wasn’t a taxi driver, but he was a forest worker and public servant. All the same, his story was remarkable enough: as the son of a leading communist activist and theorist, he had once sat on the knee of Lenin’s widow — “The only thing in my life worth mentioning,” he said. The concentration on the clever and creative worried Inglis, conscientious historian that he was. Was he selecting internees whose lives were closest to the kind of life he had led as a writer and academic? Yes, surely, and in choosing the stories that most interested him, his collaborators have ensured that this remains, as they wanted it to be, “Ken’s book.”

Taken together, the stories reveal much of the Dunera experience, not least because there were so many common elements. There was the shock of arrest and internment in Britain, given that so many of them — although not all — had fled from the Nazis. Then came the unpleasantness of the journey — the British guards behaved brutally, stealing from them and generally being obnoxious and threatening. The relief of arrival in Australia followed — a place they had neither chosen nor understood to be their destination, “the arse of the globe.” The pleasures of the first decent feed on Australian soil made an impression. Several seem to have recalled that first sandwich, along with the fruit that came with it: luxuries compared with shipboard fare. There were the insensitivities and the kindnesses of those they encountered in Australia. At Hay, one internee was surprised when an Australian soldier wished him “Shabbat shalom.” The soldier had served in Palestine, and would later take a message from the internee to his sister in Melbourne to tell her that he was safe.

There was the longing for freedom as they made the best of their incarceration in Hay, Orange and Tatura; the difficulties of deciding whether to stay in Australia — which often meant joining a labour battalion, the 8th Employment Company — or return to Britain; and the lives they made following internment and war. Many realised they had been lucky on the whole, despite their discomforts. So many of their relatives had perished in Nazi concentration camps, and some in similar circumstances to their own had drowned at sea following an encounter with a German torpedo. Life in Australia, dreary as it might have been, was safer than enduring the bombs and, later, rockets landing on British cities.

The professional lives of the internees who figure here would take in art, science, history, anthropology, economics, business, journalism and psychiatry. Some, if not quite household names among Australians of their day, nevertheless led lives as public figures: economist Fred Gruen, political scientist Henry Mayer, furniture maker Fred Lowen, and the flamboyant, exasperating composer Felix Werder. Others were well known in their particular communities and somewhat beyond them: for instance, Erwin Lamm, businessman, conservative Zionist and Jewish community leader.

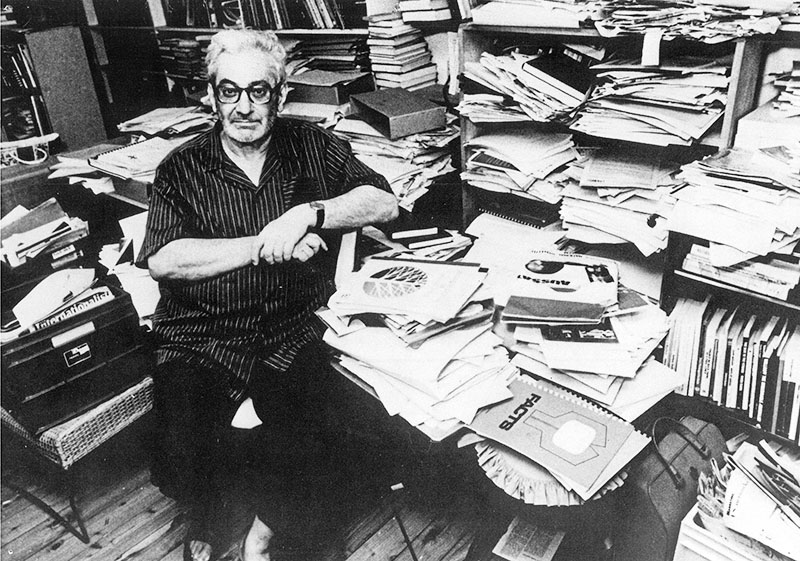

Henry Mayer in his study at home, c. 1985. Courtesy of Media International Australia © Elaine Mayer

As Glyn Davis, political scientist, former University of Melbourne vice-chancellor and an Inglis PhD student, said at the online launch of this book, it is an act of love. There is Inglis’s love for the Dunera men, and for telling stories — the passion of his professional life. But there is also the love of his friends and collaborators, Bill Gammage, Seumas Spark, Jay Winter and Carol Bunyan, who have seen his project through to completion. Rae Frances, then dean of arts at Monash University, provided the financial support for this remarkable collaboration.

While Inglis’s research notes were substantial, and he had done some drafting, much of the book remained to be written at the time of his death. These accomplished historians have done a splendid job of seeing the project through in a manner that seems, so authentically, to realise Inglis’s vision. Winter, probably the world’s most eminent historian of the first world war, is a Yale University professor now based in Paris. Gammage, a friend of Inglis for more than fifty years and colleague at the University of Papua New Guinea, is one Australia’s leading social historians; with Inglis, he was a major contributor to the modern reappraisal of Australia’s involvement in the first world war, in his case through his book The Broken Years and role as an adviser on Peter Weir’s film Gallipoli. Spark, a younger historian whose work has been mainly on the second world war, began as Inglis’s research assistant but became a full co-author and close friend. And the Canberra-based Bunyan has built up a formidable knowledge of the Dunera affair over many years of painstaking research, work that continues.

Few of us are capable of inspiring the kind of devotion and loyalty that could bring such a team together. The two volumes of Dunera Lives are a remarkable conclusion to a career and a life. Even this second volume is generously illustrated, following its older sibling of 2018, which interpreted the Dunera experience through the visual record. Both are superbly produced by the excellent Monash University Publishing.

At the heart of the book lies Australia: what we were in 1940, and the very different country we would become in the decades that followed. While some of the men, women and children whose stories are told here did leave the country, the book is slanted towards the lives of those who stayed, or at least returned. Not all of those wanted to recall their connection to the Dunera. Henry Mayer did not, whereas Jules Stocky, the scion of a wealthy and well-connected German Catholic businessman, contemplated calling his daughter Dunera when she was born in 1944.

And there are those such as Heinz Schloesser — he would change his surname to Castles — who left Australia but for whom the ties were never quite cut. He returned to England with his wife and children to resume his job as the warden of a youth hostel. Their two sons, Frank and Stephen, Australian-born, would watch the sun set on their winter walks, saying, “It’s going to Australia” — and blow it a kiss before its departure.

Both sons returned to Australia as adults, to build distinguished careers as academic sociologists — one in welfare policy and the other in immigration studies. Frank’s daughter, the author Belinda Castles, has published a novel based on the experiences of her grandparents and their families. Dunera is a tale that continues to unfold, and there are many stories still to be told.

Ken Inglis would like it that way. •