The Momentous, Uneventful Day: A Requiem for the Office

By Gideon Haigh | Scribe | $24.99 | 144 pages

Not so many years ago, something alarming happened at the London headquarters of the Financial Times. An unexpected technical glitch meant a newspaper that had survived recessions, crashes and two world wars since its 1888 birth might not appear the following day.

A team of editors was dispatched to a “disaster recovery centre” up the road, one of countless backup sites that businesses worldwide have long funded so they can keep going should calamity strike their offices. After a few frantic hours, all was well and the paper came out.

How quaint that moment seems after Covid-19.

When the first lockdowns emptied the FT’s office in March, they revealed something mildly shocking: you could publish an entire daily newspaper with everyone working from home. From Goldman Sachs to Google, the story was the same. It turned out that an astonishing amount of office work could be done with no one in the office.

What’s more, once workers were given a taste of commute-free, tracksuited life, survey after survey showed they were not inclined to rush back to the five-day office week.

So what next for the office, a centre of working life for more than a century? Will it survive? Should it? And if it does, what might it look like?

If anyone has at least some of the answers, it should be journalist Gideon Haigh, a prolific author best known for his elegant cricket writing, whose interests also span crime and corporate history. His prize-winning 2012 book, The Office: A Hardworking History, weighed in at 624 pages and won much praise for its sweeping view of office culture. Now he is back with a much shorter volume (his fortieth), The Momentous, Uneventful Day: A Requiem for the Office.

The subtitle suggests Haigh thinks the office is dead, but the book is less definitive. Readers expecting a compelling forecast of what lies ahead will be disappointed. Yet the questions Haigh tackles are important, starting with the matter of why it took a global pandemic to reveal the gaping holes in office life that we have known about for years.

As far back as the 1970s, he writes, early telecommuting advocates such as American scientist Jack Nilles were arguing that workers freed of gridlocked commutes could lead happier, more productive lives. The cost savings for employers would be so considerable that teleworking programs would pay for themselves “in a year or less.” (As it happens, the Dell computer group says its flexible working programs have saved it US$39.5 million over the past six years.)

As personal computers began their remorseless advance, the futurist Alvin Toffler suggested the home would become more central as workers retreated to their “electronic cottages.” In 1980, Haigh reports, the Washington Post dispatched a journalist to see if this seemed possible; she returned with the news that people were already running small businesses from their homes, and what’s more they liked it.

“Being able to work at home freed them for more personal life,” the journalist wrote. “You don’t have to get dressed to see your computer. In fact, the morning bathrobe seems a not uncommon uniform for the first hour or two of work, with jeans appearing later.”

Sound familiar?

In 1985, Harvard Business Review published “Your Office Is Where You Are,” an article Haigh deems “one of the most perceptive analyses of office design ever published.” Its authors didn’t advocate full-time home working. But they did foreshadow the idea that plonking people at open-plan desks (or, later, their evil twin the hot desk) for eight hours a day was fine for some types of work but hopeless for anything requiring privacy or hours of deep concentration.

Yet the office stayed much as it was for another thirty-five years. Or, as Haigh puts it, “Somehow we have continued flocking to offices as rigidly as migratory birds following the change of seasons.”

Indeed, some things grew worse as cost-conscious companies cut floorspace in the wake of the 2001 tech bust and the 2008 financial crisis. The twenty-five square metres each average worker could have expected twenty years ago has now shrunk to ten, Haigh writes. “Office workers, like slowly boiled frogs, have coped, but not without discomfort.”

This leads to a notable insight: “A key reason that Covid-19–induced working from home has proven popular, I suspect, is that it has involved a restoration of privacy that the worker has lost over the last half century.”

At this point Haigh seems convinced, as many of us have been, that the genie is out of the bottle: neither employers nor the employed are likely to return to five-days-a-week office work now they know what remote working can offer. Yet he remains ambivalent, pointing out the benefits of the socialising and collaboration that come with face-to-face office work.

He rightly argues that home working does not always work for parents of young children, especially mothers. A scattered, atomised workforce, moreover, is harder to organise to resist incursions that could become more serious. How long might it be, he asks, before “the relative ease of supervision of a manager passing by becomes, in the home office, the electronic ankle bracelet of webcams and chair sensors?”

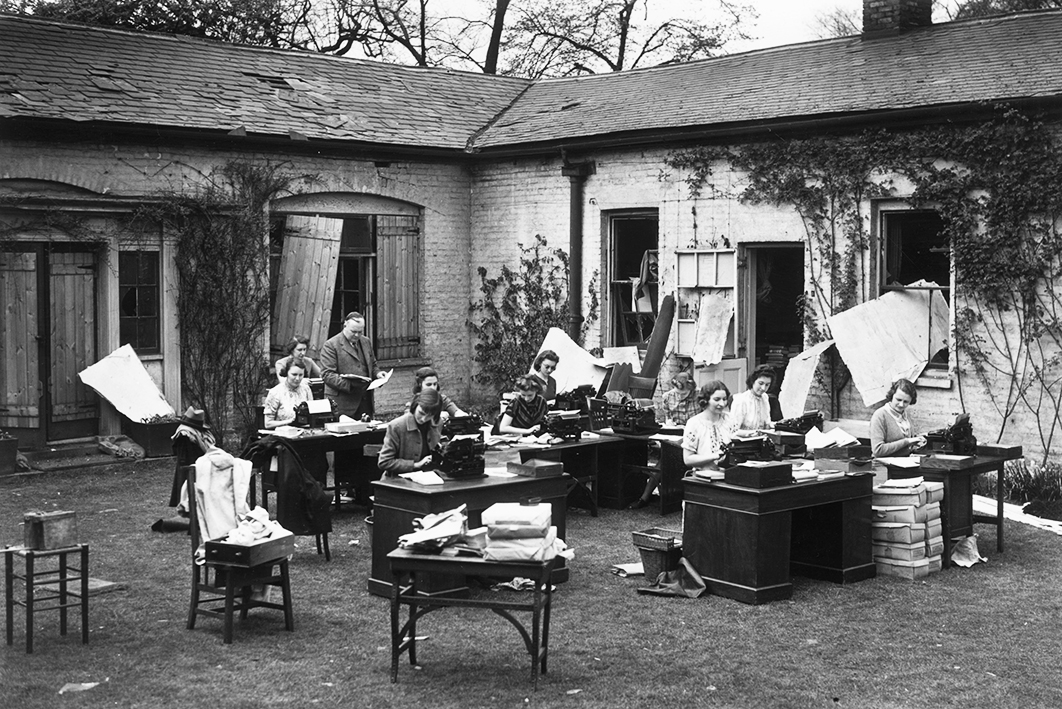

These are serious questions, and perhaps ambivalence is inevitable for a writer who has spent so long studying office history. Indeed some of the book’s most enjoyable passages come in the detours Haigh takes when looking at turning points in office history, such as the striking efforts made to deal with the arrival of female workers.

“Bosses created different male and female entrances, staggered male and female starting times, and cordoned off work and luncheon areas,” he writes. “The first female employee at the US Board of Agriculture was installed in the basement, with a firm order that no male member of staff older than fifteen was to visit her.” At Kleinwort, Sons & Co., the first female typist worked behind a screen “because one of the partners had consented to her employment only if he never saw her.”

Even the book’s title is a diversion. It comes from an 1885 novel by William Dean Howells, The Rise of Silas Lapham, which tells of a young man who discovers his place in the world through the uplifting qualities of “work we can do well”: “Every little incident of the momentous, uneventful day was a pleasure in his mind, from his sitting down at his desk… till his rising from it an hour ago.”

As Haigh writes, “paid work need not always involve a profound contribution to humanity. It can be every bit as satisfying to execute a simple task excellently.” This is true, though its connection to the office is less clear.

Enjoyable as these moments are, the book could have used at least a glancing look at what remote working pioneers can tell us about dealing with a far-flung, office-free workforce.

A case in point is Sid Sijbrandij, chief executive of the GitLab software development company, all of whose 1300-plus staff in sixty-seven countries work remotely. Sijbrandij thinks that most companies have no idea of the effort needed to make remote working work. Attempts must be made to replicate informal chats and gatherings that happen naturally in an office. Rules must be set on how to run a meeting. And so on.

But there is one other question this reviewer would have liked to have seen Haigh answer. This is his fortieth book; his career has been studded with successes. Has he achieved all this in an office? Or has he been quietly working away at his kitchen table all along? •