How did it come to this? Just a few months ago the federal government was basking in the success of having controlled the Covid-19 pandemic. Now it is lurching from one expedient to another in search of a solution to the failure of the vaccination program.

The predicament can be traced back to the government’s outbreak of self-congratulation after keeping infections so low. Hastening vaccinations was unnecessary, we were told, and there were advantages in learning more about the vaccines as they were administered in countries that didn’t have the luxury of waiting.

This was a risky strategy, as was the decision to rely so heavily on the AstraZeneca vaccine. The risk was compounded by the federal government’s decision to take the leading role in the vaccination program. Giving the states the primary responsibility for dealing with the spread of Covid-19 had made sense: they manage the hospitals and they alone had the constitutional authority to enforce a lockdown; and they would also wear the blame for mishaps and incur resentment at the restrictions. But it turned out that even the most vehemently parochial premier reaped electoral advantage from the lockdown while the Commonwealth, which paid the bills, was given little credit. This time it would take the lead.

But how? The federal government administers Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. It controls private medical insurance, subsidises aged care and supports research through the National Health and Medical Research Council. It also regulates medicines through the Therapeutic Goods Administration and buys the vaccines for the national immunisation program. But none of these activities involves treating patients, and the Commonwealth has never had the clinical expertise to undertake a mass immunisation program.

Undaunted, Scott Morrison declared that his government would procure, store and distribute vaccines and itself vaccinate “frontline” staff in quarantine and border control as well as aged care residents and their carers. To this end the health department engaged logistics companies and private health providers. The states, for their part, were to provide the clinics and health workers for the general vaccination program.

Problems quickly became apparent. Several vaccines due to arrive in the first half of 2021 were held up or, in the case of the one developed by the University of Queensland, required further work. The European Union restricted exports of AstraZeneca and the timetable for mass production by CSL proved unrealistic. Australia was to have administered four million doses by the end of March but had received just 1.57 million. Distribution to clinics was mismanaged, general practitioners left high and dry. Many aged care centres are still waiting.

The Commonwealth took on a further responsibility: it would provide “timely, transparent and credible information” on the progress of the vaccination program. From the outset it failed to do so. Each setback was dismissed with assurances that the timetable would be met. All questions were brushed aside with an airy confidence that all was well. “Our approach is to under-promise and over-deliver,” boasted health minister Greg Hunt at the end of last year.

A popular explanation for this debacle is that it confirms the federal government’s incapacity to undertake essential services. The prime minister’s explanation for his absence on holiday during the bushfire emergency of December 2019 — “I don’t hold the hose” — was widely criticised as a glib repudiation of personal responsibility, but no Commonwealth agency (apart from the army) has ever held a hose. The states have always been the providers of education, health, transport, utilities and other principal public services, and they accordingly have expertise in conducting such large undertakings.

As Centrelink’s robodebt scheme revealed, the Commonwealth’s record in administering its own programs is poor, and the Hayne royal commission criticised its failure to competently regulate the financial system. The aged care sector has been dogged by scandals going back more than twenty years to Bronwyn Bishop’s kerosene baths. The record in large national projects — the National Broadband Network, Building the Education Revolution and the National Disability Insurance Scheme among them — is little better.

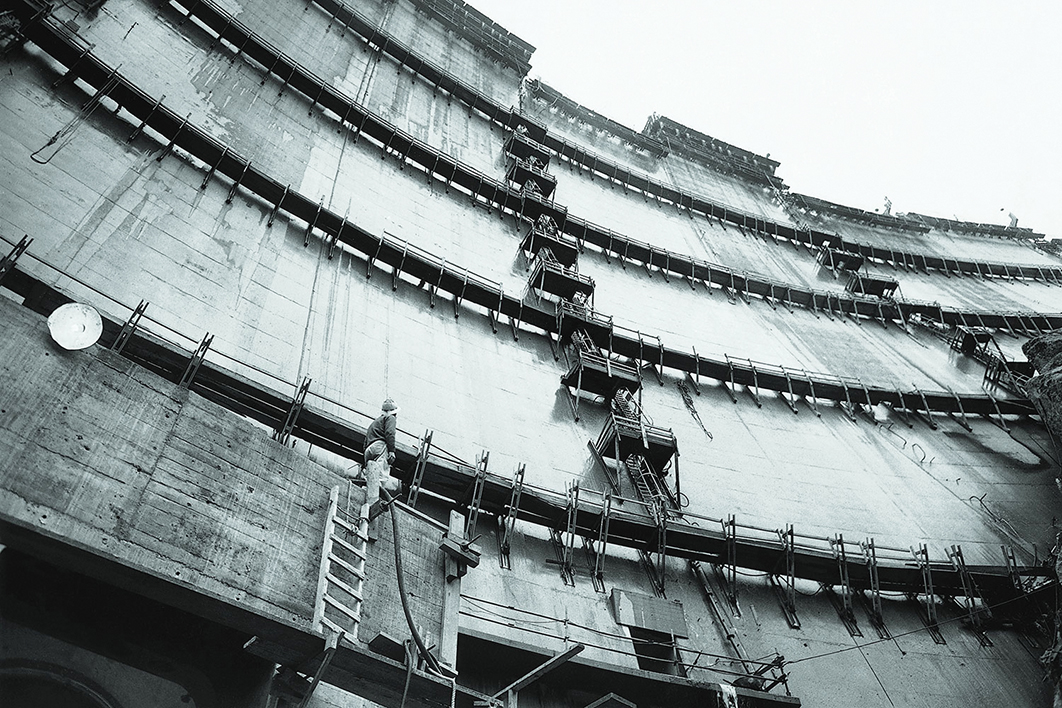

One well-known casualty was the Rudd government’s home insulation program, abandoned in early 2010 after four deaths occurred among those installing foil-lined insulation and pink batts. The program was handicapped from the beginning, hastily conceived and relying on contractors who cut corners. Even so, I recall my amazement at what quickly became the conventional wisdom: that the problems were entirely predictable since the Commonwealth was incapable of conducting major projects. My mind went back to the introduction of wartime rationing in 1942, devised and implemented with remarkable success in just three months, and the Commonwealth’s central role in the country’s largest construction project, the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme, in the 1950s.

In little more than a decade the Australian Public Service has been subjected to a score of reviews. The purpose of the most recent major report, Our Public Service, Our Future, which was published in 2019, was to “identify an ambitious program of transformational reforms to ensure the APS is fit for purpose.”

Throughout the report, the guiding assumption that Australia and its public service stood on the threshold of unprecedented change finds breathless corroboration. While “not broken,” the public service is “at a watershed,” presented with “a once-in-a-generation opportunity” to prepare for a “new era” and a “different world.” On closer inspection, this apocalyptic diagnosis rests on little more than the changes brought about by new digital platforms and interconnectivity. The problem with such technological determinism is that the history of communications is replete with technological change. On what basis is the latest judged so momentous?

An inattention to history is a feature of public policy reviews. Their frame of analysis prescribes what is to be done rather than engages with what actually happened.

A very brief passage in Our Public Service, Our Future identifies just two eras in the Australian Public Service over the past seventy years. The first, which lasted to the 1970s, was “one of public service pre-eminence — a powerful, centralised and hierarchical organisation” that exercised inordinate influence. That’s true, though the APS had almost no policy capacity until the second world war, and the powerful influence of the original mandarins didn’t extend to all departments. As territories minister throughout the 1950s, Paul Hasluck forbade his officers from making any recommendations.

The second era saw a new public management philosophy distinguished by decentralisation, program budgets, an emphasis on efficiency and performance management, rigour in program and policy evaluation, and much greater responsiveness to ministers. This new orientation is credited with enabling the reforms made by the Hawke, Keating and Howard governments.

Why, then, the need for change? The short answer is that shortcomings become apparent in any established paradigm as the world changes. What shortcomings? The report’s authors mention the depletion of expertise as a cumulative effect of the government’s efficiency dividend, the proliferation of contractors and consultants, and the continued growth of ministerial advisers. They observe that no other country with a Westminster system of responsible government allows the prime minister unfettered discretion in the appointment and termination of departmental heads.

They also note that many of the recommendations have been made in successive earlier reviews. This surely should have prompted questions. Did the government fail to accept those recommendations? Or did they turn out to be impractical or ineffective? What reason is there to think that this time they will do the trick? To ignore these question is to reinforce failure. Let’s hope those who devised our vaccination program will recognise the risk of ignoring them again. •