Exactly what happened on 1 July 1921, the day being celebrated on a massive scale this week by the Communist Party of China? Nothing much, as it happens. When Mao Zedong first thought to commemorate the party’s founding, neither he nor anyone else could remember the exact date of the meeting at which it happened — it opened on 23 July, in fact. But 1 July was the one they settled on, and it has remained the date ever since.

Beyond the light shows, the awards ceremonies, the patriotic pop and rap songs and the grand spectacular at Beijing’s “Birdsnest” stadium, a ubiquitous media, cultural and educational campaign is unfolding, all of it designed to propagate the official version of party history.

The story of the date hints at the challenges of trying to reconstruct party history. So many official versions have circulated over time, and most of them — rather inconveniently — have been preserved. In the early 1960s, Vice-Premier Lu Dingyi, a long-term political commissar and party member since 1925, came up with one solution to the problem when he explicitly forbade the writing of any party history at all. This helps to explain why, if you compare different accounts of the meeting at which the Communist Party of China was born, you’ll discover no one can even say confidently whether twelve or thirteen delegates were in attendance.

Almost certainly, two advisers from the Kremlin’s Communist International, or Comintern, were present: the Dutch communist Henk Sneevliet, who went by the alias Maring, and Vladimir Abramovich Neiman Nikolsky. The fact that Nikolsky was killed in Stalin’s Great Purge in 1938 might explain why he sometimes drops out of the story. (Mao admired Stalin.) Because no original Chinese documents from the meeting survived, the official Chinese records are translations of Russian-language Comintern documents — and these, together with the memoir of Chen Gongbo, a founding member who left the party soon after, provide just about the only evidence as to what transpired at what was, after all, a secret meeting.

At the time of the meeting, China was in chaos. Ten years earlier, in 1911, a republican revolution had dethroned China’s last dynasty, the Manchu Qing, which had been in power since 1644. Military aggression, land grabs and unequal treaties imposed on China by imperialist powers including Great Britain, France, Japan and Czarist Russia had left China impoverished, humiliated and, as the saying went, “carved up like a melon.” The first president of the new republic, Yuan Shikai, sabotaged the attempt to establish a stable democratic government when he declared himself an emperor of the “China Empire” in 1915. From then on, warlords — military men with a territorial base and an army to defend it — fought each other and what remained of the central government.

A New Culture movement had arisen on the campuses of newly established Western-style universities, demanding cultural, social, intellectual and political change, including individual freedom and rights for women and workers. Among the movement’s figureheads was Chen Duxiu (1879–1942), editor of the hugely influential magazine New Youth. Chen would be elected, in absentia, the party’s first secretary-general.

A radical thinker, Chen had readily agreed when a critic accused him of setting out to “destroy Confucianism.” He’d be happy to see the destruction of China’s “national essence,” he wrote, if that’s what it took for the survival of the Chinese people themselves. Although he had previously embraced Enlightenment and Western democratic ideals, he was captivated by the Russian Revolution of 1917. In 1919, after the Soviets relinquished all former Russian imperialist claims on China, making the Soviet Union and Marxism even more attractive to thinkers like Chen, who began to establish proto-communist organisations such as Marxist study groups. The party that today has over ninety million members claimed not much more than fifty adherents in 1921.

Having been arrested in Beijing for publishing “inflammatory literature,” Chen moved to Shanghai’s French Concession. The fact that Chinese law didn’t apply in such semi-colonial holdings — an outrageous assault on Chinese sovereignty embodied in the treaties — made them a refuge for all kinds of outlaws, including political ones. Unable to attend the founding meeting, possibly because he was by then in trouble with the French authorities, Chen sent a twenty-three-year-old student leader called Zhang Guotao in his stead.

The group convened on 23 July in a tidy grey brick house on Wantze (now Xingye) Road in the French Concession that was owned by the brother of one of their number, Li Hanjun. The Comintern representatives reportedly gave speeches on the first day, and on the second the Chinese delegates exchanged information about the work they and their comrades were doing. The next several days were devoted to drafting the party’s platform and plan.

On the evening of 30 July, tipped off by a spy who’d intruded on the meeting a short time earlier, French Concession police raided the meeting and searched the premises. Although they made no arrests, it spooked the delegates. The following day, they decamped to Zhejiang province’s South Lake, where they rented a brightly painted houseboat and continued the meeting.

This boat, rebuilt since, is now hailed as an object of veneration, a symbol of the party’s “Red Boat Spirit” and a major site for “Red tourism.” Or, as a China Daily writer put it, in a stellar example of Red prose, “That boat has sailed through turbulent rivers and treacherous shoals and voyaged across violent tidal waves, becoming a great ship that navigates China’s stable and long-term development.”

The first party congress established the Communist Party of China as a “militant and disciplined party of the proletariat” that aimed to organise workers into a revolutionary army to overthrow the bourgeoisie and seize the means of production from capitalists. Years later, following schisms within the leadership that would see Mao Zedong, one of the founders, rise to power, the party broke with the Soviet model of urban-based revolution, placing the peasantry, rather than industrial workers, at the movement’s centre. The Leninist style of party organisation they adopted at the meeting would, however, remain.

The Comintern delegates convinced the group to form a strategic alliance with the Kuomintang party of the republican revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, then leading a government in exile in the south, in the ongoing struggle against warlords and imperialists.

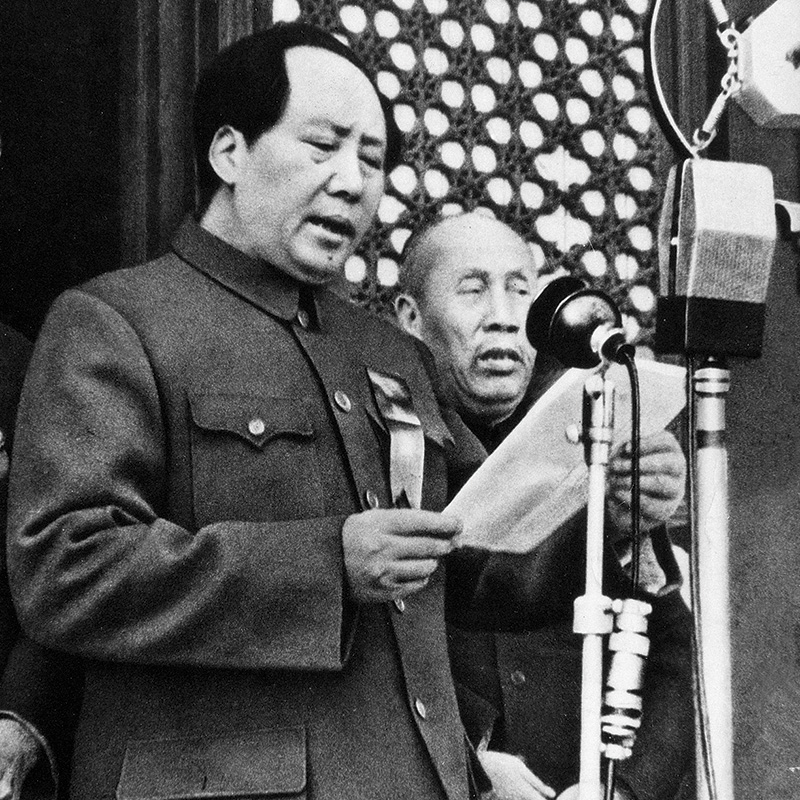

Mao Zedong (left) and Dong Biwu at Tiananmen in October 1949. Mondadori Portfolio/Getty Images

Only two of the Communist Party’s founders, Dong Biwu and Mao, would mount the rostrum of Tiananmen for the ceremony of the founding of the People’s Republic of China on 1 October 1949. By then, Mao was the party’s undisputed leader and would remain so for life. Dong went on to occupy various high-level positions in the party and state, including president of China, which he held for three years before his death in 1975 at eighty-nine, a year before Mao, too, “went to meet Marx.”

As for the first chairman, Chen Duxiu, he was kicked out of the party in 1929 for differences of opinion, including with Mao, and for his criticisms of Stalin. A Trotskyite, he spent thirteen years in a Kuomintang prison, later dying in obscurity in an isolated Sichuan village in 1942.

As for the other two original members of the “Central Bureau,” one, Li Da, also left the party in the 1920s due to differences of opinion, although he re-joined after 1949. When Red Guards attacked him in the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), he appealed to Mao, but Mao declined to save him, and he was “struggled” to death. Zhang Guotao, the third member of the Central Bureau alongside Li and Chen Duxiu, left the party in 1938 after a leadership tussle with Mao. He went into exile in Hong Kong and then Canada, where he converted to Christianity and died at the age of eighty-two in 1979.

Several founders died for the cause. The strategic alliance with the Kuomintang ended when the hardline anti-communist military man Chiang Kai-shek became effective leader of the party after Sun Yat-sen’s death. In 1927, he launched a “White Terror” that claimed the lives of 70,000 communists and sympathisers, including suspected sympathisers, among them many students.

Deng Enming, only twenty at the time of the congress, was arrested by the Kuomintang in 1929 and executed publicly two years later. He Shuheng was killed in 1935 by Kuomintang troops while engaging in guerrilla warfare in Fujian province, not long after Mao and others broke out of a Kuomintang encirclement and began what would become known as the Long March. Chen Tanqiu was killed by a warlord in 1943. A warlord also murdered Li Hanjun (1890–1927), although by then he had left the Communists for the Kuomintang.

One founder died of illness: Wang Jinmei, who participated in the party’s fourth congress in Shanghai in January 1925, succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of twenty-seven just seven months later.

After the Japanese invasion and occupation of China, two founders served as ministers in the collaborationist puppet government. One was Chen Gongbo, the author of the memoir mentioned above. The other was Zhou Fohai, who had first abandoned the communists for the Kuomintang in 1924. In 1946, the Kuomintang executed Chen for treason. Zhou, his sentence commuted to life thanks to connections, died in prison in 1948.

Two others had more complicated stories. Liu Renjing became a Trotskyite, and was first imprisoned by, and then worked for, the Kuomintang. After 1949, he wrote a statement of regret for his political sins and the Communist Party accepted it, allowing him to work in minor positions in publishing. He was victimised and imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution, but survived, and reputationally “rehabilitated” in the early 1980s. In 1987, at the age of eighty-five, he was run over and killed by a Beijing bus.

Bao Huiseng, meanwhile, had also switched sides, joining the Kuomintang, but after a brief spell in Macao, returned to the mainland with Mao’s permission. Following a period of “political study” he became a researcher in the State Council. Red Guards beat him viciously too during the Cultural Revolution, leaving him so badly traumatised it’s said that he never fully recovered. Sadly for historians, he burned approximately one hundred letters from Chen Duxiu he’d kept carefully hidden for forty years, terrified what the Red Guards might do if they found them. He died in his early eighties in 1979.

As for Maring, the Dutchman was executed by the Germans in 1942 for his part in the communist resistance to the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

If “history is a mirror,” as Xi Jinping likes to say, quoting a Tang dynasty emperor, some polishing has certainly been going on.

Just ahead of the centenary, Xi helped inaugurate a spanking new exhibition hall devoted to party history: the Museum of the Communist Party of China. Located in a nouveau-Stalinist pile near Beijing Olympic Park, it holds some 2600 photos and 3500 “relics” that present the story of the party’s history over the last century exactly as its leaders want it told. It is, in Xi Jinping’s words, a “sacred hall.”

Language like that suits a party that describes itself as “Great, Glorious and Correct” and has launched what amounts to an enormous campaign of catechism in party doctrine. There is even a hotline for dobbing in heretics — or in the party’s language, “historical nihilists,” anyone who questions the official version of party history. Xi believes “historical nihilism” contributed to the fall of the Soviet Union.

The spectacle and the careful polishing of the historical mirror are all about cementing the party’s legitimacy as the rightful rulers of China, for the next hundred years and beyond. The central role of Xi Jinping and “Xi Jinping Thought” in the celebrations shows that he has every intention of guiding it as far into that future as possible. But if there are any lessons to be had from stories of the founding fathers, it’s that where you begin is not necessarily where you end up. •

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.